Dialogue (25 page)

Authors: Gloria Kempton

Cyrus stumped over to him and grasped him by the arm so fiercely that he winced and tried to pull away. "Don't lie to me! Why did he do it? Did you have an argument?"

"No."

Cyrus wrenched at him. "Tell me! I want to know. Tell me! You'll have to tell me. I'll make you tell me! Goddam it, you're always protecting him! Don't you think I know that? Did you think you were fooling me? Now tell me, or by God I'll keep you standing there all night!"

Adam cast about for an answer. "He doesn't think you love him."

The father's heightened emotion keeps the scene moving quickly because people in a heightened state of emotion are unpredictable. You never know what they're going to do next. But once Adam tells his father this, his father immediately turns away, walks out the door without another word, and the boys' mother begins to rationally explain away her younger son's behavior, slowing the scene down.

"He doesn't think his father loves him. But you love him—you always have."

Adam did not answer her.

She went on quietly, "He's a strange boy. You have to know him — all rough shell, all anger until you know." She paused to cough, leaned down and coughed, and when the spell was over her cheeks were flushed and she was exhausted. "You have to know him," she repeated. "For a long time he has given me little presents, pretty things you wouldn't think he'd even notice. But he doesn't give them right out. He hides them where he knows I'll find them. And you can look at him for hours and he won't ever give the slightest sign he did it. You have to know him."

I did mention above that you could slow a scene down by adding bits of narrative, description, and background to your dialogue scene. In the next chapter, we see Adam again, after spending four days in bed recovering from his brother's beating. This scene is very brief but shows how you can use narrative, description, and background to make a scene move more slowly, even though there's dialogue in the scene.

Into the house, into Adam's bedroom, came a captain of cavalry and two sergeants in dress uniform of blue. In the dooryard their horses were held by two privates. Lying in his bed, Adam was enlisted in the army as a private in the cavalry. He signed the Articles of War and took the oath while his father and Alice looked on. And his father's eyes glistened with tears.

After the soldiers had gone his father sat with him a long time. "I've put you in the cavalry for a reason," he said. "Barrack life is not a good life for long. But the cavalry has work to do. I made sure of that. You'll like going for the Indian country. There's action coming I can't tell you how I know. There's fighting on the way."

Can you see how just a little bit of narrative, background, and description can make a scene of dialogue move more slowly? There's little emotion in the above scene, only the glistening of Adam's father's tears. But his words are matter-of-fact. We get the background first, then his father simply offers a half-baked explanation for why he's doing what he's doing, and the scene is over.

gaining control

Pacing your dialogue is about gaining control of your scenes so they don't run away from you or drag to the point that even you can't stay awake while writing them.

What exactly causes us to lose control of our stories and therefore the pace of our dialogue?

Losing control happens for a number of reasons and again, when we're conscious of this, it's easier to stay in control. Of course, the very act of losing control is an unconscious one. By definition, that's what losing control is, whether in real life or in storytelling. To lose control is to lose consciousness. During the act of writing a story, what causes us to lose consciousness so the dialogue suddenly begins to speed out of control or painfully drag along?

I think we often underestimate the personal connection we have to the stories we write. We think we're writing about characters we've made up. After all, this is fiction, isn't it?

Yes and no.

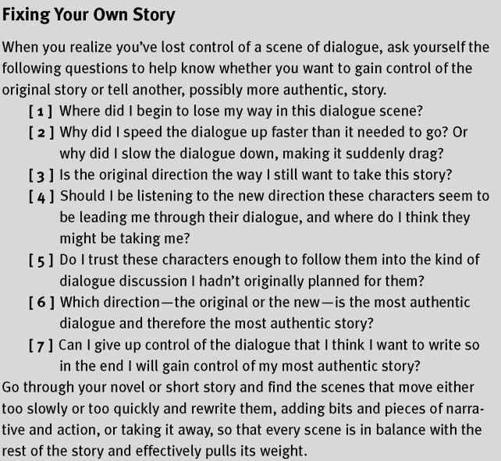

When our dialogue begins to take our characters to places we hadn't intended faster than we intended to go there, we need to pay attention. Most writing books will tell you that when this happens, you need to go back to where you began to lose your way and fix the dialogue right there, to pick up the thread where you lost it and start over.

This isn't necessarily true. Losing control of our dialogue at certain points simply means we're finally feeling the freedom to say those things we've always wanted to say to whomever we've wanted to say them. They're our words rather than our characters' words, and at this point, if we recognize what's going on, the story may turn out to be about something we hadn't intended at all. You may think you're writing about a young man landing his first job and then discover you're really writing about a young man thrust into adulthood before he feels ready. Maybe this is your story, after all, one you've never told. When you realize this, you have a choice. You can keep following the real story or you can go back to where you lost your way and get the dialogue back on track with the story you started out to tell. If you choose the second option, that's fine, but at some point you should

consider writing the real story as well, because you can count on it being the most authentic one. The one that's inside of you crying to get out.

A sudden change in pace when we're writing dialogue can signal to us that we need to pay closer attention to what the scene is bringing up for us personally. Sometimes the dialogue will speed up and we'll lose control because, yes, we've touched on a theme in our real life. But instead of going ahead and writing authentic dialogue, we become uncomfortable with the

feelings

connected to the dialogue and so quickly, go off on some tangent to get away from them. Again, awareness is what gets us back on track.

When a dialogue scene slows way down so that it drags, and this doesn't happen as often, the reasons for it are the same as when it speeds up too fast. When our characters start talking to each other again, it can happen that we come upon a personal theme that we unconsciously decide to explore, and we have to slow down in order to fully follow where it seems to be leading us. We may start weighing it down with actions of the other characters or too many of the protagonist's thoughts. We're really into this before we realize it has nothing to do with the original topic of dialogue.

We always have a choice. We can follow the tangent and see where it leads us or we can arrest the dialogue we're writing, set the real story aside for later, and continue.

We always hear about how being a control freak is such a negative thing. But maybe, in the world of writing, our efforts to gain control of our dialogue, and therefore our stories, means that we're control freaks in a good way because we're trying to write the most authentic story possible.

is it working?

How do you know if your dialogue is paced well? This is often something you can't know until you've finished the story. When reading through the entire story, you'll be able to see where you need to speed a scene up here, slow a scene down there, add a bit of setting here to keep things steady, and a bit of narrative there to momentarily let the reader breathe again.

You want a combination of slow and fast-paced scenes, alternating them so you don't either wear the reader out or put her to sleep. In Jack Bickham's book

Scene & Structure,

he instructs us to write both scenes and sequels. The scenes move more quickly while the sequels are often more nondramatic moments in the story where both character and reader catch

up with themselves. There are no hard and fast rules. Certainly there will be times where you'll need two or three fast-paced scenes in a row to move your plot along. But just be conscious of when you're doing what so you stay in control of your story.

Don't worry too much about pacing while you're writing. Just get the story down. Then put on your editor's hat and with a purple or green pen (it's a new day—no red pens anymore), go through the story and mark the places where you want to speed things up or slow them down. Following are some questions you can ask about your viewpoint character to try to discover if a dialogue scene is moving too slowly or too quickly.

• Is he talking too fast, not giving the other characters time to answer?

• Is he avoiding the subject and rambling on about nothing that has anything to do with what the story's been about so far?

• Is he thinking too much and not talking enough? Or is it the other way around?

• Are there too many tags and other identifying actions so his words become lost in the clutter?

• Is he making speeches instead of interacting with the other charac-ter(s)? (You may want him to make speeches in order to slow things down; just be aware that you're doing it and make sure that the speeches further the plot.)

• Is he too focused on observing the other characters in great detail or describing the setting to himself, sacrificing the kind of dialogue that would create tension and suspense in the scene?

• Do you, as the author, keep intruding on the scene with your own observations and descriptions that interrupt the flow of dialogue between the viewpoint and the other characters?

You can never completely know when you're going over a hair into dialogue that moves too slowly or hanging back a hair with dialogue that doesn't move quite fast enough, but the above questions will get you close enough. As always, awareness of pacing your dialogue is what will eventually get and keep you on track.

Seeing dialogue as either brakes or accelerator will help you stay in control of your story so it doesn't leave you in the dust like a runaway stagecoach or move at a snail's pace. You're the one who can press hard on the gas to propel the dialogue into motion or hard on the brakes to slow it way down. Every story has its own rhythm and motion, and pacing your dialogue to pace your story will give your reader an easy and smooth ride.

The next chapter is closely connected to this one in that it, too, is about controlling your dialogue so it's always full of tension and suspense, ensuring that your reader will keep turning pages from beginning to end.

Pacing your story. Focus on just one scene in a story you're writing. Now answer the following questions as honestly as you can:

• Is this a slow-paced or a fast-paced scene? Or neither?

• In relation to the entire story, what kind of pace do I want this scene to have?

• What is making this scene move so slowly (or quickly)?

• How much dialogue have I used in this scene, as compared to action and narrative?

• Using more or less dialogue, how can I adjust the pacing of the scene.

• Are the scenes on either side of this one slow or fast-paced?

• How much dialogue have I used in the scenes on either side of this one? Do either one of them need more or less dialogue to make them move better, so they're in rhythm with this one?

Now rewrite the scene so it moves at the pace you want it to.