Destiny of the Republic (48 page)

Read Destiny of the Republic Online

Authors: Candice Millard

W

hen they moved into the White House after Garfield’s inauguration, James and Lucretia brought with them their five children (from left to right: Abram, James, Mollie, Irvin, and Harry), as well as James’s widowed mother, Eliza. “Slept too soundly to remember any dream,” Lucretia wrote in her diary after her family’s first night in the White House. “And so our first night among the shadows of the last 80 years gave no forecast of our future.”

(Illustration credit 1.10)

A

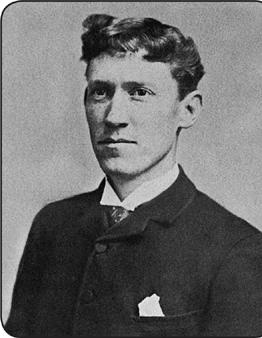

t just twenty-three years of age, Joseph Stanley Brown was the youngest man ever to hold the office of private secretary to the president. Brown’s most difficult job was keeping at bay the hoards of office seekers who demanded to see the president. “These people,” Garfield told his young secretary, “would take my very brains, flesh and blood if they could.”

(Illustration credit 1.11)

A

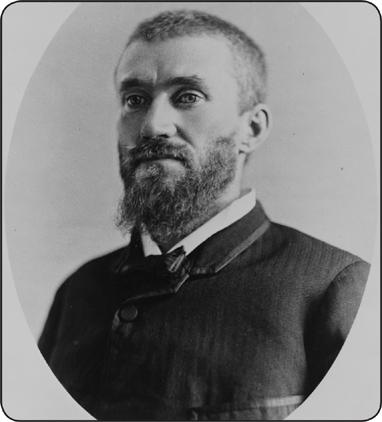

lthough thousands of office seekers flooded Brown’s office, one man stood out as an “illustration of unparalleled audacity.” Charles Guiteau visited the White House and the State Department nearly every day, inquiring about the consulship to France he believed the president owed him. Finally, after months of polite but firm discouragement, Guiteau received what he felt was a divine inspiration: God wanted him to kill the president.

(Illustration credit 1.12)

I

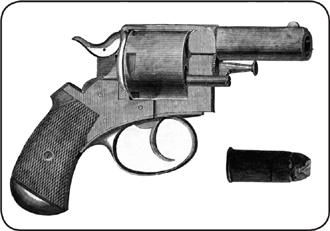

n mid-June, Guiteau, who had survived for years by slipping out just before his rent was due, borrowed fifteen dollars and bought a gun—a .44 caliber British Bulldog with an ivory handle. Having never before fired a gun, he took it to the Potomac River and practiced shooting at a sapling. “I knew nothing about it,” he said, “no more than a child.”

(Illustration credit 1.13)

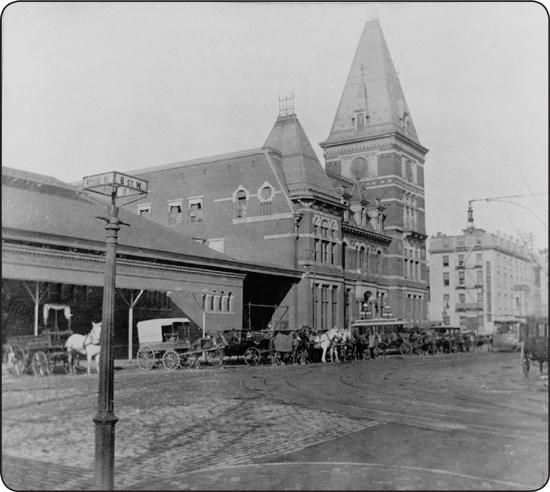

O

n the morning of July 2, Garfield and his secretary of state, James Blaine, arrived at the Baltimore and Potomac train station (

below

), where Guiteau, who had been stalking the president for more than a month, was waiting for him. The assassin’s gun was loaded, his shoes were polished, and in his suit pocket was a letter to General William Tecumseh Sherman. “I have just shot the President …,” it read. “Please order out your troops, and take possession of the jail at once.”

(Illustration credit 1.14)

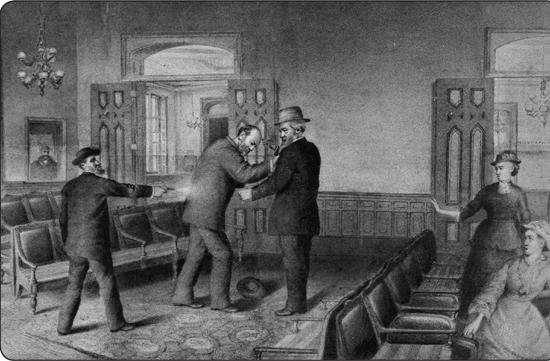

J

ust moments after Garfield and Blaine entered the waiting room, Guiteau pulled the trigger. The first shot passed through the president’s right arm, but the second sent a bullet ripping through his back. Garfield’s knees buckled, and he fell to the train station floor, bleeding and vomiting, as the station erupted in screams.

(Illustration credit 1.16)

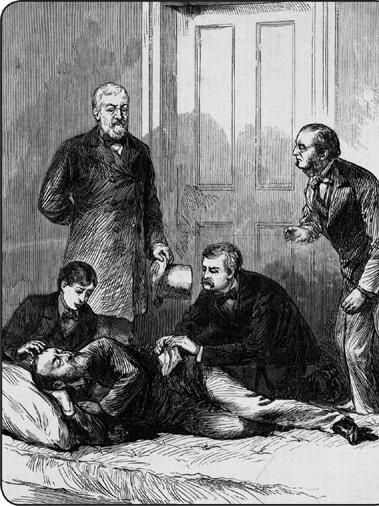

W

hile Guiteau was quickly captured and taken into custody, Garfield was carried on a horsehair mattress to an upstairs room in the train station. Surrounded by ten different doctors, each of whom wanted to examine the president, Garfield lay, silent and unflinching, as the men repeatedly inserted unsterilized fingers and instruments into the wound, searching for the bullet.

(Illustration credit 1.17)

S

ixteen years before Garfield’s shooting, Joseph Lister had achieved dramatic results using carbolic acid to sterilize his operating room, and his method had been adopted in much of Europe. In the United States, however, the most experienced physicians still refused to use Lister’s technique, complaining that it was too time-consuming, and dismissing it as unnecessary, even ridiculous.

(Illustration credit 1.18)

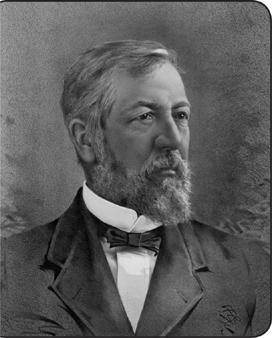

A

lthough a crowd of nervous doctors hovered over Garfield at the train station, Robert Todd Lincoln, Garfield’s secretary of war and Abraham Lincoln’s only surviving son, quickly took charge, sending his carriage for Dr. D. Willard Bliss, one of the surgeons who had been at his father’s deathbed. Bliss, a strict traditionalist, was confident that the president could not hope to find a better physician. “If I can’t save him,” he told a reporter, “no one can.”

(Illustration credit 2.1)