Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) (632 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of George Eliot (Illustrated) Online

Authors: George Eliot

Were such love-message worthily bested

Save in fine verse by music renderèd.

He sought a poet-friend, a Siennese,

And “Mico, mine,” he said, “full oft to please

Thy whim of sadness I have sung thee strains

To make thee weep in verse: now pay my pains,

And write me a canzòn divinely sad,

Sinlessly passionate, and meekly mad

With young despair, speaking a maiden’s heart

Of fifteen summers, who would fain depart

From ripening life’s new-urgent mystery, —

Love-choice of one too high her love to be, —

But cannot yield her breath till she has poured

Her strength away in this hot-bleeding word,

Telling the secret of her soul to her soul’s lord.”

Said Mico, “Nay, that thought is poesy,

I need but listen as it sings to me.

Come thou again to-morrow.” The third day,

When linked notes had perfected the lay,

Minuccio had his summons to the court,

To make, as he was wont, the moments short

Of ceremonious dinner to the king.

This was the time when he had meant to bring

Melodious message of young Lisa’s love;

He waited till the air had ceased to move

To ringing silver, till Falernian wine

Made quickened sense with quietude combine;

And then with passionate descant made each ear incline.

Love, thou didst see me, light as morning’s breath,

Roaming a garden in a joyous error,

Laughing at chases vain, a happy child,

Till of thy countenance the alluring terror

In majesty from out the blossoms smiled,

From out their life seeming a beauteous Death

O Love, who so didst choose me for thine own

Taking this little isle to thy great sway,

See now, it is the honor of thy throne

That what thou gavest perish not away,

Nor leave some sweet remembrance to atone

By life that will be for the brief life gone:

Hear, ere the shroud o’er these frail limbs be thrown —

Since every king is vassal unto thee,

My heart’s lord needs must listen loyally —

O tell him I am waiting for my Death!

Tell him, for that he hath such royal power

‘Twere hard for him to think how small a thing,

How slight a sign, would make a wealthy dower

For one like me, the bride of that pale king

Whose bed is mine at some swift-nearing hour.

Go to my lord, and to his memory bring

That happy birthday of my sorrowing,

When his large glance made meaner gazers glad,

Entering the bannered lists: ‘twas then I had

The wound that laid me in the arms of Death.

Tell him, O Love, I am a lowly maid,

No more than any little knot of thyme

That he with careless foot may often tread;

Yet lowest fragrance oft will mount sublime

And cleave to things most high and hallowèd,

As doth the fragrance of my life’s springtime,

My lowly love, that, soaring, seeks to climb

Within his thought, and make a gentle bliss,

More blissful than if mine, in being his:

So shall I live in him, and rest in Death.

The strain was new. It seemed a pleading cry,

And yet a rounded, perfect melody,

Making grief beauteous as the tear-filled eyes

Of little child at little miseries.

Trembling at first, then swelling as it rose,

Like rising light that broad and broader grows,

It filled the hall, and so possessed the air,

That not one living, breathing soul was there,

Though dullest, slowest, but was quivering

In Music’s grasp, and forced to hear her sing.

But most such sweet compulsion took the mood

Of Pedro (tired of doing what he would).

Whether the words which that strange meaning bore

Were but the poet’s feigning, or aught more,

Was bounden question, since their aim must be

At some imagined or true royalty.

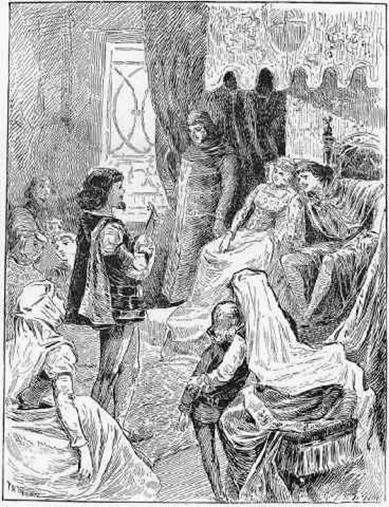

He called Minuccio, and bade him tell

What poet of the day had writ so well;

For, though they came behind all former rhymes,

The verses were not bad for these poor times.

“Monsignor, they are only three days old,”

Minuccio said; “but it must not be told

How this song grew, save to your royal ear.”

Eager, the king withdrew where none was near,

And gave close audience to Minuccio,

Who meetly told that love-tale meet to know.

The king had features pliant to confess

The presence of a manly tenderness, —

Son, father, brother, lover, blent in one,

In fine harmonic exaltatiön;

The spirit of religious chivalry.

He listened, and Minuccio could see

The tender, generous admiration spread

O’er all his face, and glorify his head

With royalty that would have kept its rank,

Though his brocaded robes to tatters shrank.

He answered without pause, “So sweet a maid,

In Nature’s own insignia arrayed,

Though she were come of unmixed trading blood

That sold and bartered ever since the flood,

Would have the self-contained and single worth

Of radiant jewels born in darksome earth.

Raona were a shame to Sicily,

Letting such love and tears unhonored be:

Hasten, Minuccio, tell her that the king

To-day will surely visit her when vespers ring.”

Joyful, Minuccio bore the joyous word,

And told at full, while none but Lisa heard,

How each thing had befallen, sang the song,

And, like a patient nurse who would prolong

All means of soothing, dwelt upon each tone,

Each look, with which the mighty Aragon

Marked the high worth his royal heart assigned

To that dear place he held in Lisa’s mind.

She listened till the draughts of pure content

Through all her limbs like some new being went —

Life, not recovered, but untried before,

From out the growing world’s unmeasured store

Of fuller, better, more divinely mixed.

‘Twas glad reverse: she had so firmly fixed

To die, already seemed to fall a veil

Shrouding the inner glow from light of senses pale.

Her parents, wondering, see her half arise;

Wondering, rejoicing, see her long dark eyes

Brimful with clearness, not of ‘scaping tears,

But of some light ethereal that enspheres

Their orbs with calm, some vision newly learnt

Where strangest fires erewhile had blindly burnt.

She asked to have her soft white robe and band

And coral ornaments; and with her hand

She gave her long dark locks a backward fall,

Then looked intently in a mirror small,

And feared her face might, perhaps, displease the king: