Dedicated to God (27 page)

Authors: Abbie Reese

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Rituals & Practice, #General, #History, #Social History

Sister Mary Gemma believes that suffering can bring good, purifying a person’s soul of selfishness and uniting her with the suffering of Christ. Although the reasons for this suffering remain a mystery, Sister Mary Gemma believes that God is an all-powerful being, an “infinite genius.”

Daily, Poor Clare nuns pray for those who call the monastery seeking relief from their circumstances. The nuns seek treatment for their own ailments as well. Mother Miryam underwent knee replacement surgery after postponing it several times, insisting she was too busy overseeing the monastery’s operations to take a break for the operation and a period of recovery.

“Suffering gives us empathy for others because you’re understanding more the suffering of Christ in a certain sense; there’s no way He loved us more than suffering on the cross for us,” Sister Mary Gemma says. “That kind of gives you an appreciation of what He suffered for you. … It really does have an effect on your love of Christ, if you don’t become bitter about suffering, and use it to draw closer to our Lord on the cross. And then you can’t help loving Him more. Of course, some people don’t have to suffer to have empathy for others. … Actually, what really purifies us for God is love; loving God and loving our neighbors is what really purifies us. But sometimes we have to suffer. … It’s how God purges away our selfishness, is through suffering. He can use our suffering for souls, for the salvation of souls. And I know from my experience that your union with Christ deepens

through suffering. He allows suffering for a reason. There’s two ways that you can handle suffering in your life—either trusting God, or you can turn to bitterness. But your spiritual life deepens when you suffer and you learn how to suffer graciously.”

Sister Mary Gemma is not speaking abstractly. Not only did she suffer and empathize as witness to her sister’s struggles, but Sister Mary Gemma has also endured her own physical trials. She, along with another member of the Corpus Christi Monastery, are both victims of serious diseases. One of the two nuns is now healed; any sign of the disease has vanished. The other nun continues to wrestle not only with her condition but also with the degree of self-care required to accommodate the affliction. Both reconcile their illnesses, and their present states, through the looking glass of faith.

Sister Mary Nicolette was diagnosed with dermatopolymyositis, a rare autoimmune disease, in childhood; the illness, which causes muscle weakness, flared twice. “I had recovered both times, but it’s a hereditary disease that you don’t usually ever get over,” she says. “You just live with it the rest of your life.” A daily regimen of expensive medication stabilized her condition, and Sister Mary Nicolette learned to deal with the symptoms, limiting her physical activity and monitoring her health.

When Sister Mary Nicolette applied to enter a cloistered monastery in Ohio, she mentioned the disease in her application, not expecting it would bar her entry since her condition was stable; she was turned away. In 1993, Sister Mary Nicolette was twenty years old when she was invited to join the Corpus Christi Monastery as a postulant. She brought a year’s worth of medication, not wanting her illness to present a financial burden to her new religious community.

She fulfilled her duties, including the sometimes demanding manual labor required of all novitiates, under close medical surveillance; regular blood tests tracked her enzyme levels. Tests revealed that she was stable, but she felt weak, with limited mobility in her muscles and tendons. “If you didn’t know that I had this, most people wouldn’t notice, but there were some things, like bending, that took a lot of effort to do,” Sister Mary Nicolette says.

But the more she worked outdoors, the stronger she felt. Several times during regular consultations with the doctor who makes house calls to the monastery, she said she did not think she needed the medicine anymore. The physician suggested reducing the dosage. “So it was gradual,” Sister Mary

Nicolette says. “Very gradual, very gradual, very gradual.” Eventually, she was no longer on any medication, “which is very unexpected and very out of the ordinary for this illness because it’s not something you’re ever cured of.”

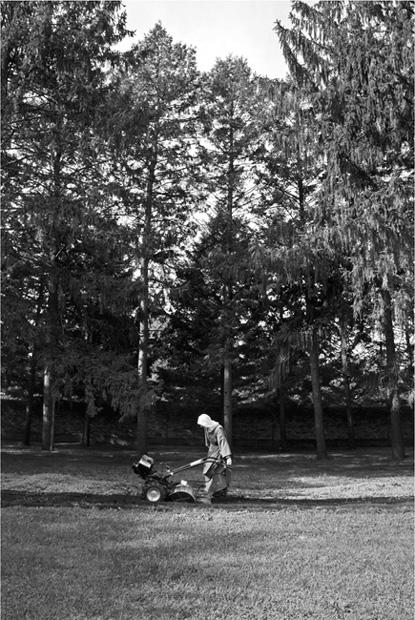

Today, she has no sign of the illness. She does not take any medicine. She no longer undergoes blood tests. “And I’m as strong as an ox!” she says. Sister Mary Nicolette knows why she was healed. “God,” she says. “I just feel like if there’s a need in the community, especially with the outdoor work and everything, the older sisters can’t do that and I’m here and I can do it,” Sister Mary Nicolette says. “And I think God strengthened me to serve community in that way, and do some of the manual work that maybe some of the older sisters can’t do.”

Asked if she thinks she would have been cured if she had not entered the monastery and assumed the trying duties of a cloistered contemplative nun, Sister Mary Nicolette says, “That’s an interesting question I don’t know the answer to.” She pauses, then adds, “Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know. It’s something very mysterious to me and perhaps only God knows. But I do feel like there was a purpose at the time when I became sick—to draw me closer to God—and there was a purpose why I was healed, so I that I could help community and be a strong sister in the community.”

Sister Mary Gemma grew up in a nearby farming community. In 1975, she entered the monastery. She was nineteen. Assigned the manual tasks of a novitiate, Sister Mary Gemma began experiencing chronic back pain. Seven years after entering the monastery, she experienced a type of pain she had never felt before: a burning sensation that seemed to jump from one area to another, traveling up and down her arms and legs.

The pain began to spread. She did not understand what was happening within her; she had trouble finding words to accurately depict the sensation. Changes in the temperature seemed to trigger discomfort, as did any sort of emotional strain.

After years of pain, punctuated by more tests and a trip to a pain clinic in Chicago, doctors eventually diagnosed her with fibromyalgia. Her condition did not improve with treatment, however, and so doctors conducted more tests. Almost two decades after the pain started, Sister Mary Gemma’s hand swelled up and turned blue; this helped the physicians deduce the underlying cause: reflex sympathetic dystrophy (RSD), known also as complex regional pain syndrome. Her doctors believed the previous diagnosis

was correct, too, and that she also has fibromyalgia. Possibly the result of a previous injury, RSD had operated with free reign, advancing unchecked for so long before Sister Mary Gemma was diagnosed and treatment started that in spite of potent doses of daily medication, small changes in temperature and minor injuries provoked major flare-ups.

Once, her hands began to ache while she was playing the organ but she kept practicing; it took her a year and a half for the pain to subside. “RSD just takes a long time to quiet down,” she says. “It’s not a nice disease. I actually have a mild form of it, but the doctor said the problem with me is it’s gone into my legs and my arms, and since I’ve had it so long, it’s harder to cure.”

Sister Mary Gemma’s treatment has included nerve blocks—temporary fixes that limited the pain for less than a year. Through trial and error, Sister Mary Gemma tries to accept her chronic condition and manage it with rest and medication (covered by Social Security disability payments). Even too much excitement or laughing too hard seems to awaken pain signals from hibernation. “Clearly a weird thing,” she says.

Doctors have told Sister Mary Gemma that her symptoms will improve if she can avoid cold temperatures as well as heat, which makes her sweat; they suggested she move from Illinois to a more temperate climate. “I just feel this is where God wants me,” she says, “and I feel so much that the community here understands my disease. They’re so understanding of it. I felt like it would be a burden to put on another community just like that, although I’m sure other communities would be willing to take me. But the sisters have grown with me. They’ve been with me through the whole thing. They’ve been supporting me through the whole thing. And I just … this is my home. They provide heat for me and they do everything they can for me to help me.”

Sister Mary Gemma believes she would not have been accepted into this religious community if her diagnoses had been made before she asked to join. She does not regret her decision to become a Poor Clare, in spite of the fact that her condition might have been detected and stabilized sooner if she had been living a more “normal life” out in the world, she says. “I think it’s a blessing for me that I’m in the monastery because I have a community who—they’re all very understanding. There are times where I cannot work at all and I have to rest a lot. I don’t know how I would survive if I wasn’t in the monastery.”

Sister Mary Gemma does not fully comprehend her affliction. She knows her body has failed her. God never intended suffering or death, Sister Mary Gemma says. “Our body and our soul are a unit. He did not make us to be spirit only, like the angels, and He did not make us to be body only, like the animals; He gave us a body and soul and He did not intend, in the original plan, for the body and the soul to be separated.”

Like her younger sister, Sister Mary Gemma prays for her own healing. She closes her prayers just as Mary did—that God’s will be done. She has not experienced substantial healing, physically. But she believes that suffering can serve a redemptive purpose. And she believes that God has answered her prayers. “I think God has helped me, not with an actual miracle, but He has helped me get the doctors that can help me,” she says. Since childhood, Sister Mary Gemma grappled with issues relating to her self-esteem. Once, a few years ago, when she received the Sacrament of the Sick, she says, “I can remember that I was asking our Lord to heal me in whatever way He wanted to, and I felt a great strength emotionally after that.” Another time, as Sister Mary Gemma observed her hour of prayer before the exposed Blessed Sacrament, she knelt down and said, “Jesus, I failed you again. And I felt His voice coming from the Blessed Sacrament going right to my heart: ‘I love you still.’ I was so surprised, I said, ‘Jesus did you just talk to me?’ ” Sister Mary Gemma says. “I didn’t hear it again. But I felt it so strong. It felt like an echo in my heart and it was one of those things that kept me going through this tough time of low self-esteem. He loved me anyway. And He loves me anyway.”

An assistant in the infirmary, helping watch over Sister Ann Frances as she contended with Alzheimer’s, Sister Mary Gemma is thankful that Sister Ann Frances can remain in the monastery and has not been sent to a nursing home, where Sister Mary Gemma thinks she would be even more confused. Working in the infirmary allows her a more flexible schedule. Not wanting to “spoil herself,” she has had to learn, repeatedly, not to try to soldier through the early warning signs of RSD; otherwise she will need to be admitted to the hospital to receive intravenous pain medication. A necessary regimen—frequent rest—feels like punishment for the sociable Sister Mary Gemma.

Mother Miryam says it is hard for any of the nuns when they cannot take part in community because they are sick and bedridden, but it has been especially hard for Sister Mary Gemma when she is forced to remove herself to her cell. Mother Miryam says Sister Mary Gemma questions, “Am I giving

in to myself?” Mother Miryam describes Sister Mary Gemma as phlegmatic by nature and not prone to push herself; she says Sister Mary Gemma has made great strides in the steep learning curve to know how much she can handle once she feels pain and when she should stop working.

Sister Mary Gemma does not walk barefoot—unlike the fictional Ingalls family, unlike the other Poor Clares. RSD forbids her feet from greeting the cold floor. “That’s part of my suffering, too, because I came here to live a life of penance and to live a hard life, and I’m not able to do that because of my health situation,” she says. “And yet I am living a hard life within my situation. It’s hard for me not to live the life as I thought I was going to. Through spiritual direction, I’ve learned to accept it; this is how God wants me to suffer. He wants me to suffer by not being what I would call a

Colettine

Poor Clare. We have a very strict penitential life and that is what I came for, but it’s God’s plan that I’m not able to do that. I suffer in a different way.”