Death of an Empire (48 page)

Read Death of an Empire Online

Authors: M. K. Hume

‘Carthage sings in its salt-sown ruins. Rome is dead! Greece rejoices in the memory of its greatness that you are on your knees.

Gaul is free to tear itself into bloody rags, while Hispania shivers in the darkness, waiting for the warriors of the crescent to cross the Middle Sea and enslave its people anew.

‘Look down from your heights, Holy City, and know that the glory is all fled . . . and will never return, although untold centuries wash over you, rebuilding and destroying, until the end of all things.

‘Woe to you, Flavius Aetius! For you will die at your master’s hands.

‘Woe to you, Valentinian! You have cut off your own strong hand and now you await the assassin’s knife. Beware the Field of Mars.

‘Mourn, Petronius Maximus, emperor for three score days before the mob tears you limb from limb and, later, no man will care to speak your name.

‘A river of blood has been shed in your name, whore city, but now you will drown in the tides that you have loosed.

‘And woe to you, Myrddion Emrys, for you will lose what you valued, to hold that which you sought.’

Then Myrddion turned and would have spoken, but his eyes rolled upward in his head and he collapsed like the boneless straw men that are used to frighten away the crows that gorge on the wheat fields.

For one agonised moment, his own face loomed over him in his inner darkness and pointed to a bloody child. Then the infant lifted a long, steel sword and stabbed his heart.

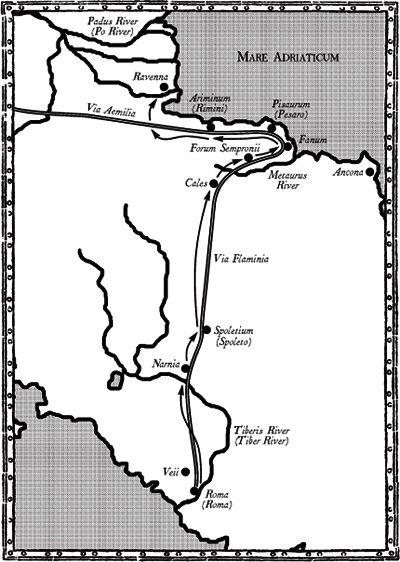

MYRDDION’S CHART OF THE ROUTE FROM ROME TO RAVENNA

A ROSE-RED WOUND

‘Every man slaughters his true desires by trying to hold them too closely,’ Myrddion cried out as he woke to a grey morning. His head thudded with an insistent headache that threatened to cause it to explode. As he opened his eyes to dim, rain-drenched light, he imagined that his brain was leaking out of his ears, eyes and nose. He vomited weakly over the edge of his pallet.

‘Master? Praise the gods, you live!’ Finn called out. ‘Cadoc, come quickly! The master is awake – he’s sick, but awake.’

Over the agonised pounding in his ears, Myrddion recognised the rich, deep voice of Rhedyn, now high-pitched with distress. He closed his eyes to lessen the pain and experienced a corona of dancing, jerking, coloured starbursts behind his eyes. Trying to move his agonised head as little as possible, he vomited again into the bowl that the widow held to his mouth.

‘What can we do to help you, master?’ Finn pleaded, but his voice had a far-away sound.

‘Are you a spirit, Finn?’ Myrddion asked, his mind dazed in childlike confusion. He frowned as the weak light struck at his senses, so he closed his eyes once more and the world went away for a few minutes.

In response to an insistent hand shaking his shoulder, Myrddion

dragged his eyes open with an enormous effort of will, and there were Finn and Rhedyn standing before him as they tried to support his shaking shoulders.

‘I’m ill,’ Myrddion explained unnecessarily, as if to backward children. Nothing made any sense, as if his flesh and his spirit were dislocated and he couldn’t reassemble the shattered pieces.

‘Drink, master,’ Cadoc ordered, his face looming out of the darkness at the edges of Myrddion’s vision. ‘Open your mouth and don’t force me to pinch your nose shut.’

‘Would you poison me, my friend?’ Myrddion whispered, so Cadoc took the opportunity to force the bitter liquid down his master’s throat. Choking and protesting, he tried to shrug his apprentice away, but his arms refused to respond to the orders from his brain. He felt himself flailing at the air like an invalid.

‘I’ll not poison you, master, trust me,’ Cadoc pleaded as he forced the cup against Myrddion’s teeth until the healer submitted and swallowed the last of the soporific draught with a choking cough.

As a roaring, echoing darkness carried him away, Myrddion felt the inner part of himself release its rigid hold on his mind and body. Then, in a long, slow wave, he felt his senses slip away. Mercifully, that cruel inner vision let him be.

Ravenna was shocked, titillated and thrilled by the suicide of the noble Gallica Lydia. For the first time in many months, the older, more distinguished citizens of the second City of God spoke of her with affection and nostalgia for the old days of the Republic. The gossip was pointed in its change of public opinion. Petronius’s wife had been pure and noble, so she could not bear to live with the shame of her rape. Perversely, the old women nodded over their watered, warmed wines and agreed. Only a decent and self-respecting woman would kill herself out of shame, therefore Gallica Lydia must have been innocent.

Valentinian heard the whispers and the rumours that were circulating behind his back and experienced a frisson of anxiety, which was made more keen by the ritual hand-washing of Flavius Aetius, who now loudly proclaimed that his family had written to the beleaguered woman to offer her their sympathies, prayers and support. Valentinian watched the tide of positive public opinion turn against him and settle upon the ever-willing shoulders of Flavius Aetius.

After the inhumation of Gallica Lydia and the prescribed period of mourning, Petronius Maximus returned to Valentinian’s court. He was a changed man, for the superfluous flesh on his jaw, his shoulders and his belly had melted away, leaving him leaner and harder. Those courtiers who could meet his eyes discovered that Petronius viewed them all with a hollowed, tortured gaze that spoke eloquently of his loss. With Lydia’s suffering always in the back of his mind, contempt flared in Petronius’s face when noble citizens expressed their sympathy or pressed his hands encouragingly. Even Gaudentius refrained from making jokes or leering in the senator’s direction, reading something stark and deadly in the set of Petronius’s lips. Nervously, the young epicure lowered his eyes whenever the senator passed.

Heraclius was uncomfortable in the presence of the newly silent, introverted senator. Petronius was far too brooding to be predictable, and for the first time the eunuch wondered if he had been wise to embroil himself with a man who was so inexplicably volatile. Had Heraclius realised that Petronius actually loved his wife, he would not have approached the senator so blithely with his treasonous plot.

‘Romans don’t usually care for their wives overmuch,’ he explained to his lover that first evening of Petronius’s return to the court. ‘Marriage is more about treaties, the size of the dowry and the purity of the bloodlines than affection. I’d swear that the

senator was half mad with grief – dangerously so, in fact.’

‘My dear, Romans don’t think like rational men and women,’ his partner responded casually. ‘Who’d be foolish enough to kill themselves over a sexual misadventure? Those who serve the throne in menial matters know that shame can be survived, but death is final. Instead of being treated like a fool, Lady Lydia is now praised. It’s ironic, my darling boy. Yet earlier, at a time when sympathy would have helped her, she was castigated by her own kind. And it all happened because she was raped. Better to serve barbarians than belong to Romans.’

Heraclius’s hirsute lover kissed the eunuch’s shoulder until the Greek grew impatient and pushed him away. The strapping young man pouted and stalked out of Heraclius’s private bedchamber.

Can I control Petronius? Heraclius wondered. What will Valentinian do when he is forced by proximity to meet the senator? By the gods, I wish I had left well enough alone.’

Meanwhile, Valentinian tossed in his luxurious bed. He had ordered his wife to leave him, preferring to sleep alone as was his custom. Part of his need for privacy was driven by fear – of assassination and of having to comply with the needs of others – but it was also motivated by his burning desire to be invisible in a world where nothing and no one was ever solitary. From his earliest memories, Valentinian had been conscious of having to share every aspect of his privileged life with others. His adored mother had belonged to the empire rather than to himself, and something of that small boy still endured in his desire to be free of the bonds of his position.

Poor Valentinian! Like the possessions of all weak men, his Empire had come to resemble his own inner qualities. In the wake of Attila’s invasion, the Empire was weak and dependent on the strength of ambitious and clever acolytes who were more able than he was, causing him to become terrified of the world

that existed outside his luxurious apartments. But now Valentinian had cause to fear the powerful family that hovered on the very edge of his throne, especially its paterfamilias, Aetius, who was the direst emergent threat to Valentinian’s continued trouble-free existence.

‘Can I trust my guard to rid me of Flavius Aetius? Would the Praetorians obey me? Not a chance! Many of the guard are barbarians and those ruffians love the old fox, damn his eyes. So who can I trust to serve my needs?’

Valentinian’s voice rasped harshly in the silent room, even though he whispered in the darkness so that the guard outside his door should not hear the words he shared with the night. To speak his internal anxieties aloud gave strength to his thoughts. One after another, he discarded possible assassins who could be trusted with the task of murdering the greatest general in the Western Empire.

Outside the locked door, Valentinian’s personal guard heard the muffled rumble of the emperor’s voice as he spoke to himself. They wondered if, at last, their master had succumbed to the madness that affected so many members of the Roman patrician class.

Throughout the night, Valentinian tossed and turned in an agony of indecision. He admitted to himself that he was frightened of the

magister militum

who had wielded influence over the Empire for the whole of Valentinian’s adult life. He couldn’t imagine a world without Aetius in it. Even a glimpse of that compact, bandy-legged figure with its bald dome and fringe of iron-grey hair filled Valentinian with dread. His smile! Valentinian had a child’s certainty that Aetius used those cruel, narrow lips to point out the emperor’s craven inner self to anyone who would listen. The emperor squirmed with self-knowledge.

What could Aetius do? How would he begin his attack on the

emperor? Valentinian was certain that the Scythian was aiming his sights at the throne of the Western Empire, not because Petronius Maximus had suggested it, but because of the bad blood that now lay between Aetius, Petronius and himself. Gods, the senator had gone so far as to voice his suspicions of Aetius openly, and to swear that the general would enjoy the spectacle of the emperor’s death throes.

In his usual self-serving fashion, Valentinian was exaggerating. The first day Petronius Maximus had returned to court, ghost-ridden and guilty, Valentinian had made the mistake of speaking publicly of the senator’s loss.

‘My regrets, senator. Your wife was a beautiful and accomplished woman. I’m sure you must miss her.’

In hindsight, Valentinian admitted that he should never have grinned quite so widely or so obviously. Petronius Maximus had glared at him with grief-stricken, angry eyes, so the emperor knew in the pit of his stomach that he had made a careless tactical error.

‘I swear that I will do nothing to imperil the throne of the west, my emperor,’ Petronius had vowed. ‘Not in word, nor in deed. My love for Rome has been tested a thousand times and my wife’s . . . death is but another test of my loyalty. I prefer to put my trust in the Three Fates and the goddess Fortuna, whose wheels, shears and caprices rule us all.’

Valentinian was not a fool, merely lazy, spiteful and spoiled. He noted Aetius’s sudden rigidity at the ambiguity of Petronius’s little speech, so he was sure that the general had read messages into those words that Petronius refrained from voicing. As the long day trailed away in doubt and anxious indecision, Valentinian drank too much wine to spare himself from the horrors of his dreams. Eventually, supported by Heraclius and a member of his personal guard, he staggered drunkenly to his bed.

Once he was safely ensconced in his room, he latched the door

from the inside and, with a dagger for company and consolation, plunged into a drink-sodden sleep. Heraclius listened to the iron and wood latch fall into position and walked away down the colonnade, smiling gently as he went about his duties.

In Rome, winter had come with a vengeance and the city shivered in her damp and mud-draggled skirts. Myrddion had taken more than a week to recover from his illness, terrifying his servants, who had been deathly afraid for his survival. Stray draughts and breezes were banned from his room by the use of the last of their heavy linen from Aurelianum, which was nailed over the window frame, an action that Myrddion thought wasteful once he returned to his senses.

‘Never fear, master,’ Bridie replied equably, as she sat and spun lamb’s wool into long threads on her spindle. ‘When we leave this cursed place, we can easily take the linen down and boil it, and then it will be as good as new.’

During Myrddion’s frightening illness, Cadoc and Finn had decided that they should all leave Rome as soon as they could retrieve their wagons and horses. Pulchria was visibly upset at the news of their impending departure, and would bury her face in a piece of colourful gauze, burst into tears and totter away on her tiny feet every time she saw any of the small group of healers.