Death of an Empire (4 page)

Read Death of an Empire Online

Authors: M. K. Hume

‘Perhaps battle will claim him while we are absent from Britain. I’ve had my fill of arrogant, powerful masters who ride roughshod over the dreams of ordinary men.’

‘Not him. He’ll survive the worst that fate can throw at him and still flourish. We’d best be gone before first light, for I’d not put it past that devil to steal you away for the sake of his precious honour.’

‘Aye.’ Myrddion nodded in agreement. ‘Wake me at dawn.’

The night was as cold as ever and the dried grasses under the copse of trees made an uncomfortable and itchy bed, but Myrddion was suddenly so exhausted that he couldn’t keep his eyes open. He plunged into the river of sleep as if he meant to drown himself, and through the marshes of the darkness night-horses sent horrors after him until his cries disturbed the other sleepers and Finn was forced to wake him with a worried frown.

Londinium was a city that had been infiltrated and defeated by stealth. As the healers rode through its outskirts, heading for the southeastern roadway that would lead to Dubris on the coast,

Myrddion couldn’t fail to recognise the hordes of Saxon traders clogging the Roman streets and a growing accumulation of filth where the clean outlines of stone drains had been become blurred with rubbish. The Roman passion for cleanliness was beginning to fade, while Celt, Saxon and dark-skinned traders from other lands hawked their wares in an argot of many mixed languages. Myrddion spied Romanised Celts dressed in togas and robes wearing expressions of permanent confusion, as if puzzled by the changes that had turned Londinium into a slatternly city.

‘The barbarians have taken Londinium without a single blow. See the traders? And beyond the villages, there are northern palisades that have no place in these lands.’ Cadoc’s face whitened a little and he shook his head like a shaggy hound. ‘Londinium can’t be allowed to fall, lord. What will happen to us if all sorts of wild men gain a foothold here?’

‘I don’t know, Cadoc,’ Myrddion whispered softly. ‘Hengist and his sons have set down roots in the north of the country, so many more Saxon ships will soon follow from the east. Before I die, I fear that the days will come when our whole green land will belong to the invaders . . . and our customs will be consigned to the middens of the past. Change has come, my friend, whether we want it or not.’

Cadoc was affronted by Myrddion’s opinion, so he busied himself by carefully handling the reins of the four horses that were dragging the heavy wagon. ‘The Saxons won’t be permitted to lord it over our people while we can still fight. I know what those bastards are like. They destroy everything that is good in the name of their savage gods.’

‘I hope you’re right, Cadoc, but reason tells me that a change has come and only a fool pretends he can stop it. The Saxons aren’t wicked, just determined to find a permanent home. Perhaps Uther Pendragon can stop them, if anyone can.’

‘Now there’s a horrible thought,’ Cadoc muttered as he concentrated on controlling his team.

‘As you know, the cure is sometimes worse than the illness,’ Myrddion whispered, but his words were blown away in the stiffening breeze from the sea.

The inhabitants of the towns of the south were nervous and inclined to be suspicious of strangers, for these people had endured the invasions led by Vortigern’s Saxon bodyguards, Hengist and Horsa, and struggled with Vortimer’s bloody retribution for their incursions into the Cantii lands, so the local elders now waited for the void created by warfare to be filled by some new, as yet unknown, threat. Strangers were not to be trusted, for lies come easily to the lips of greedy and ambitious men. But healers were in demand, so the wealth in Myrddion’s strongbox gradually increased through payments of silver and bronze coin and the odd rough gem, besides the barter of fresh vegetables and eggs in return for their ministrations. Of necessity, such aid as they could offer to the citizens along the road to Dubris slowed their journey as well as enriching them, while bringing new dangers of robbery from unscrupulous and desperate outlaws.

Finn Truthteller had been grimly silent as they passed the hillock of greening earth where so many Saxons had died during Hengist’s war, and he shuddered as he spied the standing slab of marble with its carving of the running horse. Knowing that Finn still suffered the lash of memory and a shadow of dishonour, Myrddion joined his servant in the second wagon as they passed an old, fire-scarred Roman villa.

‘You need not be concerned to look upon the ruins left by the Night of the Long Knives, friend Finn,’ the healer offered when he saw the shaking hands and quivering lips of his friend. ‘Hengist’s revenge on Vortimer’s Celts was no stain on your honour.’

‘I am the Truthteller, Lord Myrddion, and Hengist left me alive

to testify to the death of Prince Catigern at this place. Many good men perished here, but I was saved to recount the tale. I’ll not run from a memory, master. I can’t. Better to face my ghosts and save my sanity.’

Myrddion laid one sensitive hand on Finn’s arm where he could feel the bunched muscles that were a mute betrayal of Truthteller’s internal suffering. ‘You’re right. I somehow expected the villa to be larger and more oppressive than it is, when you consider its reputation. But, like all bad dreams, its reality is far less impressive than the memories it holds. It has become a worthless pile of fire-scarred bricks and stone rubble. See? The trees are beginning to grow through the open rooms and little will soon remain to remind us of what happened here.’

‘Aye,’ Finn replied slowly, as Myrddion felt some of the tension leave the man’s arm. ‘Weeds are covering the cracked flagstones and ivy is breaking up what is left of the foundations.’ Then, just as Myrddion thought that Finn had managed to banish his constant companions of shame and guilt, the older man cursed. ‘I wonder if Catigern lived for a time under Horsa’s body?’ Myrddion saw a single tear drop from Finn’s frozen face.

‘I don’t know, Finn. But if he did, Catigern deserved to suffer. He was a brutal man who is better under the sod. He’d have betrayed us all for the chance to win a crown.’

‘Aye,’ Finn replied once more. He shook his brown curls and used the reins to slap the rump of the carthorse. ‘Better to be off on the seas and away from these bad memories.’

Dubris still retained its links with the legions in its orderly roadways and official stone buildings, but the healers could see evidence of the growing malaise of carelessness in the pillaging of the old forum for building materials. Marble sculptures of old Roman gods had been carted away to be crushed and turned into lime,

leaving empty plinths of the coarser stone so that, uneasily, Myrddion fancied that Dubris was cannibalising its own flesh.

But the docks displayed the bustle and industry of any busy port. Vessels of all types jostled for moorings along the crude wooden wharves, while traders haggled with ships’ masters in half a dozen exotic languages. Running, grunting under the weight of huge bundles, or driving wagons drawn by mules, oxen and the occasional spavined horse, servants and slaves moved cargoes to warehouses or loaded ships with trade goods for the markets across the narrow sea that linked Britain and the land of the Franks. Above the din of commerce, Myrddion could barely make himself heard as he gave his instructions to Cadoc.

‘Sell our horses for the best prices you can get,’ Myrddion ordered as he ran an experienced eye over the rawboned beasts as they strained under their heavy loads. ‘Judging by the standard of animals we can see here, you’ll get a good price for our horseflesh. The wagons will have to go as well, but remember that we’ll have to buy others once we make landfall. Don’t let the bastards cheat us!’

‘It’ll be my pleasure, Master Myrddion. The traders will pay good coin, or I’ll make up the difference myself. However, we might need to wait for a few days to win the best prices. They’ll fleece us bare if they smell any desperation on our part.’

‘We can afford to wait for several days, for the spring sailing has only just begun. Besides, I’m sure we’ll have our first customers before the day is out.’

As usual, Myrddion read the tone and desires of Dubris correctly. Even before the travellers had found an inn to provide them with moderately clean shelter, the grapevine of gossip had whispered of a skilled healer in the port and Myrddion, his women and his servants were soon profitably at work.

Nor was it difficult to find a suitable vessel to continue their

journey. The ship they chose was captained by a dour northerner who plied his trade between Dubris and the Frankish lands to the east, and was more than willing to bear passengers who wouldn’t need to fill his wide-bellied ship with their own goods. Prudently, Myrddion paid a quarter of the agreed price in advance and sealed the deal with a handshake.

A week later, Dubris became a disappearing line of dirty haze in the charcoal skies behind them, and the Frankish port of Gesoriacum became an equally vague suggestion in the heaving seas before them. They were about to enter foreign climes, and Myrddion was still boy enough to feel his heart lighten with excitement. His mother might detest him because of the violence of his conception, and his beloved Olwyn had been buried on the sea cliffs above the straits of Mona isle, but Myrddion was still young and vigorous. Somewhere beyond the haze on the horizon were libraries full of learning, new ideas that would fire his questioning mind and a whole new world of sensation. Somewhere, out in the far-off corners of the world, the object of his quest might lead him to his destiny.

The seabirds followed the wallowing vessel and squabbled over the food scraps that were tossed overboard. Like all scavengers, they were careless of the needs of their fellows, so they fought for their spoils with the intensity and ferocity of starving beggars. Even their cries were like eerie curses that followed Myrddion, sending his thoughts winging onwards towards the east and to the man he sought out of all the millions who populated lands that bordered the Middle Sea.

And yet his reason called him a fool for allowing himself to pursue such a useless undertaking. An old cliché echoed in his brain, full of warning and threat, so he spoke the words aloud to rob them of their sting. ‘Be careful what you wish for . . .’

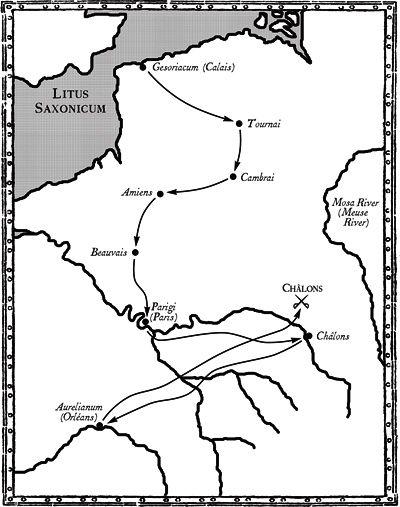

MYRDDION’S CHART OF THE ROUTE FROM GESORIACUM TO CHÂLONS

ON THE ROAD TO TOURNAI

All journeys end, especially short, wind-driven dashes across the narrows of the Litus Saxonicum. As the sailors responded to the barked orders of the weather-beaten ship’s master, expertly using the single patched sail to catch the wind, Myrddion marvelled at the skill that drove the wallowing, wide-bodied vessel to tack ever nearer to the docks of Gesoriacum. The ravenous, noisy gulls, their constant companions on the journey, cursed the ship as it made its untidy arrival at the battered wooden wharves of the old Roman port. With one last chorus of pungent insults, the seabirds departed for mud flats that promised mussels, cockles and the detritus of a very dirty seaport.

Gesoriacum was still ostensibly Roman, although the filthy inns on the seafront were home to men of all races, sizes and degrees of bad temper. While the three women who served the healer protected their master’s possessions and made vain attempts to ignore the lewd invitations uttered in half a dozen equally incomprehensible languages, Myrddion and Cadoc sought out a trader who was prepared to sell them two stout and weatherproof wagons and the beasts to power them.

Like all ports, Gesoriacum was grimy, mud-spattered and vicious, offering every form of vice that brutal men could desire.

Dispirited prostitutes of both sexes stood against the salt-stained buildings trying to keep themselves dry in a steady drizzle of rain. Drunkards cluttered up the roadways and reeled argumentatively out of wine shops, eager to take offence if a stranger crossed their path. Ferret-eyed men promised good sport with dogfights, cockfights and even illegal scrimmages between desperate men who would win a few coins if they could beat their opponents into a bloody pulp. The air was stale with the smell of seaweed, drying fish, excrement and desperation, so Myrddion walked carefully with one hand on the pommel of the sword he had inherited from Melvig.

‘Shite! Watch where you be putting your clodhoppers, you horse’s arse,’ a half-drunken sailor cursed before he spotted Myrddion’s sword and noted Cadoc’s angry eyes. ‘Your pardon, master,’ he muttered and would have scurried away, suddenly sober, if Cadoc hadn’t gripped his torn tunic with a muscular, scarred hand.

‘Do you know of any place in this flea-bitten billet where we can purchase wagons and horses?’ Cadoc rasped in the Celtic tongue.

Nonplussed, the sailor shook his head, and Cadoc was forced to repeat the question in sketchy Saxon, backed with Myrddion’s Latin, which was almost too pure for the man to understand.

Finally, he pointed one grimy paw down a darkening back alley. ‘Try that Roman pig Ranus. He deals in horseflesh, if he hasn’t sold them all to the army. And if there are any wagons to be had, he’ll know where they can be found – at a profit to him.’

Even before Myrddion could thank him, the sailor had slipped eel-like out of Cadoc’s grasp and scampered down a dark lane like a sleek, black rat. Cadoc wiped a greasy hand on his jerkin with an exclamation of disgust. ‘Doesn’t anyone wash in this hellhole? That bastard’s sweat reeks of cheap ale, and my hands will stink for weeks.’