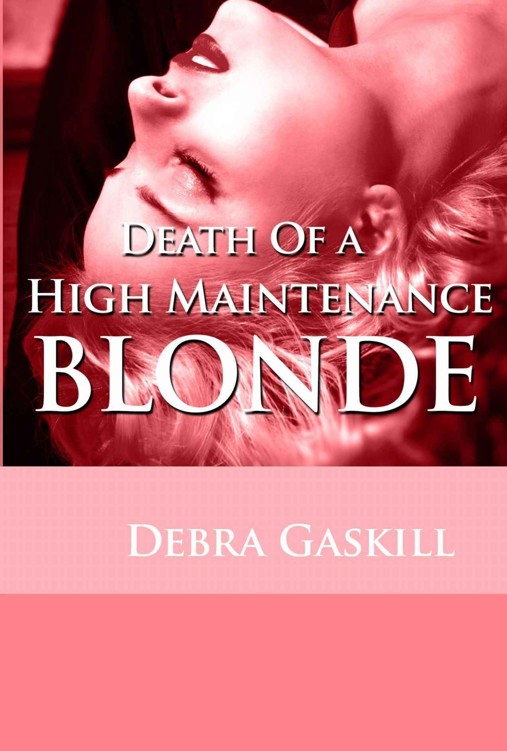

Death of A High Maintenance Blonde (Jubilant Falls Series Book 5)

Read Death of A High Maintenance Blonde (Jubilant Falls Series Book 5) Online

Authors: Debra Gaskill

Death of a High Maintenance Blonde

By

Debra K. Gaskill

© 2014 Debra Gaskill

All rights reserved.

ISBN:

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the express written consent of the author.

Cover design © 2014 Rebecca Gaskill

Published by D’Llama Publishing, Enon, Ohio

This is a work of fiction. The situations and scenes described, other than those of historical events, are all imaginary. With the exceptions of well-known historical figures and events, none of the events or the characters portrayed is based on real people, but was created from the author’s imagination or is used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

“It is awfully easy to be hard-boiled about everything in the daytime, but at night, it is another thing.”

—Ernest Hemingway,

The Sun Also Rises

Chapter 1: Addison

I sat up in bed, gasping for air.

Sweat glistened on my body, and my heart pounded. After forty years, I could still hear the roar of the tornado as it ripped through my hometown of Jubilant Falls, Ohio, that April day in 1974.

I was back cowering in the root cellar of my grandmother’s Victorian home as winds of more than two hundred fifty miles an hour roared around the big, white house like freight trains at high speed. The smell of the cellar’s moldy dirt walls was as fresh in my nostrils tonight as it was the afternoon my grandmother, Ida Addison, in her home-sewn cotton apron and orthopedic shoes, covered me while the windows upstairs exploded from the unequal pressures inside and outside the house.

I saw his body again, too. Lying beneath a tree on his grandfather’s farm, Jimmy Lyle was one of the tornado’s victims, pinned to the earth with the posthole digger he’d been using when the storm struck.

At least that’s what everyone said happened to him. What other proof did they have? Even forty years later, something told me ‘they’ were wrong.

I didn’t have the dream very often, but when I did, the terror was still very real. I reached across the bed and touched my husband Duncan’s shoulder. Tonight, my dream hadn’t disturbed him and his breath came rhythmically as he slept. It was three forty-five. In just about an hour or so, he’d be up and we’d start milking our herd of Holsteins, then I’d head off to my job as managing editor of the

Jubilant Falls

Journal-Gazette

. No sense disturbing him now. I tossed the summer quilt off my legs and tiptoed down the stairs.

I flipped the kitchen light on and began to make the morning pot of coffee as crickets chirped outside in the morning dark.

It was early June, bringing with it all the promise of a hot, dry summer, so we’d left the windows open overnight. The cricket singing outside reminded me of life’s continuity, despite what that April day permanently encoded in my psyche.

The old chipped pot filled quickly. I poured myself a cup, found my lighter and pulled a cigarette from the pack on the counter, then went outside to the front porch.

The quarter moon was beginning to descend into the far western horizon as I took a seat on one of the old McIntyre rocking chairs. Separated from our farmhouse by a field of fledgling soybeans, a single Ford Explorer drove down the road, its headlights brightening the road a few feet in front of it as it hurtled toward its destination. To my right, I heard the Holsteins begin to wake from their pasture beds, mooing as they, ever creatures of habit, began to amble toward the milking parlor.

This farm had been my home for more than twenty-five years and it had always been a safe haven, as well as for Duncan and our daughter, Isabella.

Except on nights like tonight, when my nightmare came back. Why, then, since putting out a fortieth anniversary commemorative edition on the tornado, did I wake bathed in sweat and fear at least once a week? I wanted to believe it was just putting those horrible memories on paper one more time, but something down deep told me that wasn’t it.

I took a sip of coffee and leaned back into the old rocking chair. I knew from experience, the best way to get through my terror was to work through it, piece by piece. Over the years, I learned it was the only way to guarantee the next night’s peaceful sleep.

*****

After the roaring stopped, Grandma and I came up out of the storm cellar. She climbed the stairs in front of me, opening the heavy, slanted double doors that led to the back yard.

Grandma gasped as we walked into the strange, silent sunlight.

The house behind us was a smoking pile of sticks and brick. Down deep in the rubble, someone cried for help. Our lawn was littered with white wooden gingerbread and shingles from our own roof; pieces of rain-spattered glass shone among the leaves and branches from my grandmother’s magnificent backyard maples and elms. The white picket fence that separated Grandma’s ornate rose garden from our neighbor’s backyard lay fractured across the yard and into the driveway.

Like Grandma Addison’s home, the other houses on our street were stone and brick relics from another era. Because of this, most stood wounded but upright, despite whatever just blasted through our neighborhood. The frame houses on the block behind us, however, were destroyed, leaving nothing but piles of splinters and shingles. A wall of one house was completely gone, exposing an upstairs bedroom with the dresser and bed hanging precipitously over the floor’s exposed edge, a story above the ground. Smoke was beginning to show from beneath some of the piles of rubble that moments ago had been homes. Geysers shot from broken front yard water mains.

The brick coach house beside Grandma’s was the only undamaged building across our block. Grandma had converted the upper story years ago to the apartment where my father, Walter Addison, and I lived. Below Grandma parked her massive Chevy Impala, and, when he was off duty, Daddy parked his Ohio State Highway Patrol cruiser.

The cries from the rubble of the house behind ours grew louder.

“Oh, sweet Jesus,” Grandma whispered. She began to run toward the cries beneath the shattered house, then stopped and turned to me. “Penny, run to the firehouse as fast as you can and tell them someone’s trapped in Mr. Johnson’s house!”

“Why don’t you just call?” Terrified of moving, I pointed toward our house.

“We’ve had a tornado, Penny! Only the Lord knows how much damage has been done! The phones won’t be working and if they are, the lines will be so jammed, you can’t get through! Run, girl! Run, like I told you!” Grandma turned and darted toward the destroyed house.

I turned and fled, as fast as my sixteen-year-old legs would carry me.

It was two blocks to the firehouse, blocks that I’d walked thousands of times with my best friend, Suzanne, to spend my allowance downtown.

Even in this early morning’s easing darkness, I could remember the buildings as they had been before that day: the post office, the firehouse, a furniture store with an expansive parking lot, then Washington Street, followed by a solid block of merchants: a women’s clothing store, a book store, Sven Olin’s drug store with the soda fountain across the store’s dark back wall, a barber shop, a diner and at the corner with its rounded stone face, the First National Bank and Trust.

It wasn’t like that now.

As I ran, the familiar street looked like a war zone: a semi lay upended in the furniture store window, the store’s roof and two walls caved in. A Pontiac, crushed by bricks, sat in its parking spot in front of where the barbershop formerly stood. Windows were shattered; the glass crunched under my feet as I ran along the sidewalk, dodging fallen bricks. Someone’s pick-up truck was on its side in the window of the diner.

People were staggering out of damaged buildings, bloodied by the collapsing roofs and glass shrapnel. Women screamed for their children and men worked frantically to pull the wounded out of buildings. Moments ago, they’d been leaning on the counters or were waiting for a haircut, staring out the window at young men in low-slung bellbottoms and loud paisley shirts sauntering down the sidewalk.

Across the street, the old stone courthouse stood, circled in red-slate shingles from its roof, the walls largely undamaged.

Next to it, the sheriff’s brick office stood untouched, along with the jail. The art deco city building, sitting behind the courthouse on Detroit Street was also untouched.

Within minutes, I was at the firehouse. Josh Whitacre, a fireman friend of my dad’s, was in his turnout gear, ready to jump on the only fire truck left in the bay. I grabbed the sleeve of his heavy protective coat as he swung into the passenger seat.

“Please, Josh! You gotta help me! The house behind us collapsed and somebody’s trapped inside! Please! Please!”

“You’re Walt Addison’s girl, ain’t you? You OK? Ida OK?” Josh gently peeled my hand from his sleeve.

“Yes, yes—you gotta help me, please! This man, Mr. Johnson, he’s trapped inside his house—it all fell in on him—and—and—”

“I’m sorry, Penny, but the high school’s been damaged and the middle school has collapsed with kids inside—we’ve got to go there first. All of the other trucks are out on other calls. I’ll pass the information on, but we’ve got a natural disaster on our hands. You’re going to have to find some one else to help right now.” With that Josh slammed the door and the fire engine rushed out into the street, its sirens screaming.

I ran from the firehouse and into the downtown, searching for a policeman, another adult, somebody—anybody—who could help.

The dream always ended the same. I ran down an endless street strewn with bricks, branches, glass and blood. I would get close to a policeman, a deputy or just another adult and they would fade into the bloodied face of another tornado victim, just as I was close enough to plead for help.

In real life, I came home without help. Grandma never reached Mr. Johnson and after a few hours, his cries stopped. It would be two days before a National Guardsman would pull his body from the remains of his house and three days before Daddy would come home from the patrol post, exhausted and dirty from recovery work.

Mr. Johnson would be among the thirty-five people who were killed and the nearly twelve hundred injured in our town. The tornado made national news as part of more than two hundred tornados that ravaged small towns throughout the Midwest that day. Our town suffered the most casualties; even President Nixon, who came through with the governor, said he’d never seen anything like it.

As the days passed, and the death toll mounted, we learned more about the victims and the random nature of the storm. Ten of those killed were middle school students, practicing for the spring play when the school roof collapsed on them.

Then there was Jimmy Lyle, a junior at Shanahan High School, just like me. We were in English class together, working on a project about Walt Whitman.

Jimmy was on the football team and good-looking in that vapid, muscle-bound jock way. He had longish, brown hair that curled around his ears, a thin, teenaged attempt at a moustache and empty, but pretty, brown eyes.

I knew why our teacher assigned us to work together—Jimmy could use all the help he could get to move on to his senior year and maintain the team’s winning ways; I was the brightest one in the class.

His girlfriend, Eve Dahlgren, was a senior and the head cheerleader, who didn’t like seeing us working together. She was jealous, pulling him away and starting arguments with him when she saw us together at school.

“You stay away from my Jimmy, you hear me?” she would snarl.

“Baby, it’s just homework!” he’d plead, as if I needed defending. Then he’d follow her like a kicked dog down the hall to her locker. We ended up sneaking around, meeting in the library downtown to complete the assignment.

But even my efforts couldn’t keep Shanahan High School’s record-setting quarterback on the football team.

One of the tornado’s odd legacies was the way the swirling wind forced items together, shoving twigs through boards and turning harmless everyday items to weapons. Because of that, nobody ever questioned how Jimmy Lyle’s body was fastened to the ground.

Jimmy Lyle’s body was found after the tornado, out in one of his grandfather’s pastures where he’d been working at replacing fence posts. His skull was crushed from the weight of a tree branch and the posthole digger was embedded in his chest. Everyone assumed he’d taken shelter under the tree when the rain hit and he died when the branch fell on his head. The injuries from the posthole digger had to be just one of the many freaks of the storm.

His name was on a brass plaque recognizing the tornado victims, the fourth one down in the second of three columns.

I didn’t see a lot of my classmates as Shanahan High School was rebuilt. Some of them were bused, along with me to a neighboring district, where we finished the school year. A lot of other students’ parents were too terrified to rebuild and left for nearby areas not quite so prone to nature’s wrath. Eve Dahlgren’s wealthy parents stayed, but sent her to a private girl’s boarding school in Columbus. She returned each summer after college and I’d see her shopping with her mother at Hawk’s, the old department store that used to be downtown. We never spoke, but she seemed to smirk every time I caught her eye.

I took a sip of my coffee and sighed.

What was that little snot’s deal all those years ago, anyway?

I wondered.

Like many of the class of 1974, Eve would go on to college somewhere out of state and stay there, where opportunities were more plentiful. She had a big career in California or Texas or someplace. The

Journal-Gazette

did stories on her as she moved up the corporate ladder, then after her mother quit bringing in the news of her daughter’s latest promotions, the stories stopped and I happily lost touch in the mid-1990’s.

The screen door squeaked opened beside me. It was Duncan, dressed in overalls, his coffee mug in his hand, ready to begin milking.

“You got up early,” he said softly. “Bad dream?”

“Yeah,” I sighed. His hand rested on my shoulder and I lay my cheek against it.

“Same one?”

“Yeah. Forty years on, it doesn’t get any easier.”

“I’m sorry.” He gestured with his coffee mug toward the barn, where the Holsteins were lined up patiently waiting to be let in. “The girls look like they’re anxious for their breakfast. Let’s get started. You’ll forget about that bad dream soon enough.”

I nodded and stood up. He was right: I couldn’t live in the past. Duncan had been through the tornado too. He just didn’t talk about it.

After milking, the day would go on as any other. I would head into work at the J-G and the sprint toward deadline would begin again.

It didn’t matter if the image of Jimmy Lyle, leaning on a posthole digger and reciting “Oh Captain! My Captain!” never left my mind.