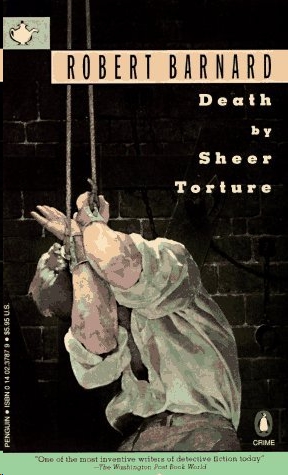

Death by Sheer Torture

Read Death by Sheer Torture Online

Authors: Robert Barnard

Thank you for purchasing this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C

LICK

H

ERE

T

O

S

IGN

U

P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: Obituary

Chapter 2: Homecoming

Chapter 3: The Painful Details

Chapter 4: Trethowans at Meat

Chapter 5: Cristobel

Chapter 6: Night Piece

Chapter 7: The Younger Generation

Chapter 8: Lunch with Uncle Lawrence

Chapter 9: Papa’s Papers

Chapter 10: Family at War

Chapter 11: Brother and Sister

Chapter 12: Low Cuisine

Chapter 13: In Which I Have An Idea

Chapter 14: In Which I Have Another Idea

Chapter 15: A Concentration of Nightmares

Chapter 16: Epilogue

CHAPTER 1

OBITUARY

I first heard of the death of my father when I saw his obituary in

The Times.

I skimmed through it, cast my eye over the Court Circular, and was about to turn to the leader page when I was struck by something odd in the obituary and went back to it.

‘As reported on page 3, the death has occurred . . .’ was how it began. That was odd. Famous actresses, disgraced politicians, exploded royalty might get their deaths reported on the news pages, but why should my father? Even the obituary had admitted that his achievements were few—had implied, indeed, that had he not been a member of a family whose fame verged on notoriety they would hardly have paid him the compliment of an obituary at all. ‘Though now rarely heard, his song-cycle

Dolores . . .’

—that kind of thing. My father’s death would shatter the world no more than it had shattered me. And in that case there must be something unusual about the death—a spectacular accident, suicide (no, not that), or . . .

Going against all my principles (for like all right-thinking people I read my paper backwards) I turned to page three. And there it was, tucked away down at the bottom: ‘Police were called to Harpenden House late last night after the death was reported of Leo Trethowan, youngest member of the famous Trethowan family . . .’ Well, well: so the old boy had gone out with a bang.

I turned back to the centre pages, but I found it hard to concentrate on the first leader (which was about changes in the Anglican liturgy, never a subject of urgent

personal interest to me). In spite of myself, in spite of the affectation of total indifference which I assumed even when alone, it had to be admitted that I was interested. My mind was already toying with various enticing speculations: a spectacular accident was of course a possibility, but it seemed to me that, knowing my father, it was odds on he had met his unexpected death at the hands of someone or other. Certainly he would not have committed suicide: he was never one to do anybody a favour. No, on the whole murder seemed . . .

It was then that the telephone rang.

‘Perry Trethowan,’ I said.

‘Hello, Perry,’ said my superior at the other end. ‘Have you read the paper yet?’

‘Yes,’ I said cautiously. ‘The Common Market summit seems to be sticky going.’

There was a second’s pause. I have a nasty vein of dry facetiousness that a lot of people find trying, and my boss was one of them. He was trying to decide whether it was operational now. ‘I was referring to the death of your father,’ he said cautiously.

‘Oh yes, I saw that.’

‘But of course, they must have telegrammed you last night anyway.’

‘No.’

‘You’ll be going down for the funeral, I take it?’

‘I hadn’t thought to,’ I said. ‘I wouldn’t be expected.’

‘Isn’t this a time to let bygones be bygones?’

‘That’s what I try to do. I finished with my family years ago.’

‘Perry, you’re being difficult. You know we’ve been called in?’

I pricked up my ears. ‘Ah. So it was murder?’

‘Yes, it was. Almost definitely. Of course there’s no question of sending you down —’

‘No, thank God,’ I said. ‘Who are you sending?’

‘Hamnet. What’s your opinion of him?’

‘Perfectly decent chap. Excellent choice.’

‘It just seemed to me that perhaps he’s a bit lacking in . . . well, imagination. And with your family imagination might be exactly what is wanted.’

‘Personally I’d have said a thoroughly nasty mind was the first requisite for anyone investigating the murder of a Trethowan,’ I said incautiously, giving him an opening.

‘Well, you should know. That’s really why we’d like to have you down there —’

‘I do not have a nasty mind.’

‘But you do know all the inside secrets. You are on their wavelength. Of course, I’d heard you weren’t close . . .’

I laughed. ‘A nice way of putting it.’

‘Do you have any financial interest in the death, may I ask?’

‘Certainly not. I was cut off without a penny. If there is anything much to inherit (which I wouldn’t bank on) it will go to my sister, which is quite as it should be: she is precisely the sort of person odd legacies do go to.’

‘He could have changed his mind, of course.’

‘My father never, but never, changed his mind.’

‘Well, that’s all to the good as far as we’re concerned.’

‘Thank you.’

‘I mean if you have as little as possible personal interest in the matter.’

‘Joe,’ I said, addressing the Deputy Assistant Commissioner in a way I would usually not do except over an off-duty pint, ‘we are both agreed, aren’t we, that I cannot have any part in the investigation of this murder? I can brief Hamnet, I can even put in an appearance for a couple of hours at the funeral. But surely nothing more can be asked of me than that?’

‘I thought,’ said Joe Grierly, ‘that since you could be down there for perfectly natural reasons over the next few days, you could be given something in the nature of a

watching brief. There are features in this case . . .’

I groaned audibly. ‘There would be features,’ I said.

‘The personalities involved, for example, present problems: I don’t know whether you knew, but one of your father’s sisters—Catherine, I think the name is—went off her head last year.’

‘How did they know?’ I asked.

‘Eh?’

‘My Aunt Kate has been teetering on the edge of insanity for fifty years. One would hardly notice when she actually toppled over.’

‘Wasn’t there something about the war?’ Joe asked, cunningly vague.

‘My aunt had various mad crushes in her teens, on people like Isadora Duncan and D. H. Lawrence, and she capped them by becoming a besotted admirer of Adolf Hitler. She used to spend her summers attending Nuremberg rallies and consorting with Hitler’s

Mädchen

in Bavarian work camps—some sort of Butlins plus ideology, I gather. They interned her in Holloway during the war.’

‘Oh I say—that seems rather hard.’

‘Not a bit: I’ve every sympathy with the authorities. If the silly . . . buzzard had kept quiet everything would have been forgotten. Instead of which she went careering round the village on her bike distributing pamphlets calling for a German victory. They really had no option. She had a highly privileged life in Holloway with others of like mind. As far as I can gather they all sat around complaining about the quality of the port.’

‘Poor old thing.’

‘She was thirty or so at the time,’ I pointed out.

‘I can see I’m not going to rouse any sympathy in you for the difficult position your family’s in at the moment.’

‘No.’

‘How did you and your father come to disagree?’

‘We never agreed. How did we come to fight? Well, you know how in the past families like ours expected their sons to go into the army, the church, manage the estate and so on, and there was a great stink if one of them wanted to go on the stage or something?’

‘Yes.’

‘Well, our family’s cussed in this as in everything else. If I’d said I wanted to go to ballet school, or train to be a drop-out, or go to the States and graduate in dope-peddling, they’d probably have patted me on the head and given me the family blessing and a couple of thou. When I said I wanted to join the army, all hell broke loose. My father said it was a pathetically conformist way of life, Aunt Sybilla said it showed a dreadfully coarse nature, and Aunt Kate said I’d be

on the wrong side.’

‘It was no better when you switched to the police?’

‘I didn’t enquire. But I assure you, no—no, they would

not

have looked more favourably on the police.’

‘Your Aunt Sybilla, she’s some sort of artist, isn’t she?’

‘My Aunt Sybilla is or was a stage designer; my Uncle Lawrence is a poet and writer of

belles lettres

sort of stuff; my father was a composer and my Aunt Kate is—well, I suppose you could call her a politician.’

‘Well, you see the problems Hamnet is going to face when he gets down there.’

‘My sympathy goes out to him,’ I said.

‘Look, Perry, it’ll be much the best thing for all of us if you go into this voluntarily. After all, they are your family. Blood is thicker than water.’

‘So my professional experience tells me,’ I said. ‘Personally, taking it metaphorically, I’ve never been able to extract much meaning from that saw. Blood is certainly

stickier

than water—that I do know.’

‘Christ, I don’t want to have to

draft

you —’

‘Oh, hell’s bells, all right. I’ll go down for the funeral.’

‘You’ll go down today. And you’ll stay down there as

long as Hamnet needs you.’

‘No wonder men are resigning from the Force in droves,’ I said. ‘This is nothing but jackboot tyranny.’

‘Have fun,’ said Joe, registering my surrender.

I was just banging down the phone when I remembered something I’d forgotten to ask. ‘Here, Joe,’ I shouted, ‘you haven’t told me how he died.’

Joe obviously resumed the conversation with reluctance. ‘I was afraid you’d ask that,’ he said.

‘Not nice?’ I asked, now really curious.

‘He died,’ said Joe cautiously, ‘while subjecting himself to a form of torture which I believe is called strappado.’

‘Oh, no!’ I howled.

‘He had it arranged, I gather, so that he could stop it at will. As far as we can see, someone fiddled with the ropes.’

‘Joe, listen,’ I gabbled, ‘you can’t send me to that snake pit. That is

just

how one of my family would die, and

just

how one of my family would murder. This is appalling. The press will have a field day. I’ll be the laughing-stock of the CID for the rest of my life. You can’t send me there, Joe —’

‘There’s a train at ten fifty,’ said the Deputy Assistant Commissioner. ‘Oh, and there’s one more tiny detail —’

‘What?’

‘He was wearing gauzy spangled tights at the time.’

CHAPTER 2

HOMECOMING

The inconvenient, and slightly ludicrous, house which my great-grandfather finished building in the last years of the Old Queen’s reign must, over the years, have brought

a small fortune to British Rail and its predecessor companies from successive generations of my family, and in its heyday, their numerous guests. Perhaps this was why the Beeching axe quivered with compunction in the early ’sixties and spared the nearest station of Thornwick, and why subsequent carve-ups of the public transport system designed to force more and more cars on to the roads have left it standing and (with reduced services) functioning. It’s not every day you meet a large family of lunatics ready to travel from Northumberland to London at the drop of a hat.