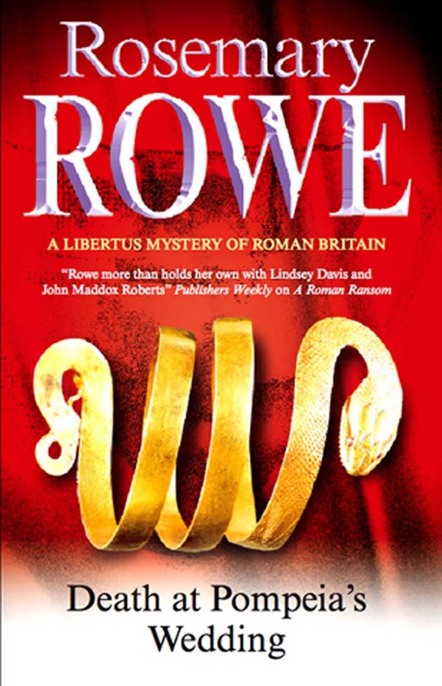

Death at Pompeia's Wedding

Previous Titles in this series by Rosemary Rowe

THE GERMANICUS MOSAIC

MURDER IN THE FORUM

A PATTERN OF BLOOD

THE CHARIOTS OF CALYX

THE LEGATUS MYSTERY

THE GHOSTS OF GLEVUM

ENEMIES OF THE EMPIRE

A ROMAN RANSOM

A COIN FOR THE FERRYMAN

Contents

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This first world edition published 2008 in Great Britain and 2009 in the USA by SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of 9–15 High Street, Sutton, Surrey, England, SM1 1DF.

Copyright © 2008 by Rosemary Aitken.

All rights reserved.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Rowe, Rosemary

Death at Pompeia’s wedding. – (A Libertus mystery of Roman Britain; 10)

1. Libertus (Fictitious character: Rowe) – Fiction

2. Romans - Great Britain - Fiction 3. Slaves – Fiction

4. Great Britain – History – Roman period, 55 B.C.-449 A.D. – Fiction 5. Detective and mystery stories

I. Title

823.9’2[F]

ISBN-13: 978-1-78010-023-4 (ePub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-6698-1 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84751-089-1 (trade paper)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk, Stirlingshire, Scotland.

For Jakob

Author’s Foreword

The story is set in AD 189. At that time most of Britain had been, for almost two hundred years, the most northerly outpost of the hugely successful Roman Empire: subject to Roman law, criss-crossed by Roman roads and still occupied by Roman garrison legions in the major towns. The province was normally governed by a provincial governor, answerable directly to the Emperor in Rome, but the previous incumbent, Helvius Pertinax, (the supposed friend and patron of the fictional Marcus Septimus mentioned in the book) had recently been promoted, first to the African provinces and more latterly to the exceedingly important consular post of Prefect of Rome – making him effectively the second most powerful person in the Empire.

There is scholarly doubt as to who was acting as Governor of Britannia at this time, one theory being that several candidates were appointed and then un-appointed by the Emperor – the increasingly unbalanced Commodus, whose erratic and scandalous behaviour was a byword by this time. He had renamed all the months, for instance, with names derived from his own titles (which he had in any case given to himself); declared that unlike his predecessors (who had been deified at death) he was the living incarnation of the god Hercules; and announced that Rome itself was to be officially retitled ‘Commodiania’. He was unpopular and feared, but still clung tenaciously to power and (perhaps justifiably) feared plots against his life. He therefore had a network of secret spies throughout the Empire.

This is the background of civil discontent against which the action of the book takes place. Glevum, modern Gloucester, was an important town: its status as a ‘colonia’ for retired legionaries gave it special privilege – all free men born within its walls were citizens by right – and a high degree of responsibility for its own affairs (local tiles of the period describe it as a ‘republic’). The members of the town council were therefore men of considerable power. They were also, by definition, wealthy men: candidates for office were obliged by law to own a property of a certain value within the city walls, and any councillor or magistrate was expected to contribute to the town, by personally financing elaborate games, fountains, statues, arches, drains and public works. Though they might expect to gain a little too, in service or in kind, from the contractors whom they appointed to the work. The sudden rise of a comparative unknown – like Antoninus in the story – seeking to be made a councillor, would therefore be a matter of concern, not least in case the newcomer might be the Emperor’s spy.

Councillors were often local magistrates as well, like the ageing Honorius in the tale. Roman law was universal at this time, but it did make clear distinction between the punishment which might be meted out to citizens, and that which might be given to other freemen for the same offence. (Slaves, of course, were in a different class again.) Many of the more savage punishments had by this time been repealed, and others (such as the ‘sack’ for parricide) had fallen out of use, though there is evidence that some jurists wanted them renewed – rather as the hanging lobby does today. The right of the paterfamilias to wield life and death over his children was by this time largely gone, except in the case of a father who – as in this story – catches his married daughter with a man who is not her husband, if not ‘in flagrante’ then at least in part undressed. In this case the father was entitled to execute the man – to protect his family honour – provided that he killed his daughter too, otherwise he might be charged with homicide.

Power, of course, was vested almost entirely in men. Although individual women might wield considerable influence and even manage large estates, females were excluded from civic office, and indeed a woman (of any age) remained a child in law, under the tutelage first of her father, and then of any husband she might have. Marriage officially required her consent (indeed she was entitled to leave a marriage if it displeased her and take her dowry with her), but in practice many girls became pawns in a kind of property game, since there were very few other careers available for an educated and wealthy woman – though some low-ranking citizens (like Maesta in this story) might continue to help their husbands in some form of trade.

The wedding ceremony might take several forms. The most prestigious was the oldest form, the ‘confarratio’ which required a solemn religious ceremony and the sharing of a pecial wheat wafer (hence the name) in the presence of a group of Roman witnesses. This kind of marriage was indissoluble and by the time of the narrative was becoming very rare – for one thing it required the presence of two senior priests of Rome (the Flamen Dailis and the Pontifex Maximus) so it was not available in the provinces, and for another it removed the bride from her father’s ‘manus’ to her husband’s power and her former family had no further claim on her (or on her dowry or her children) even if he died. Another form, the ‘usus’ marriage, which simply required uninterrupted cohabitation for a year, was widespread among the poor; there are instances of women annually spending a night with their sister or mother so that the marriage was not finalized, and thereby keeping a degree of independence in their own affairs.

Pompeia’s marriage, the basis of this book, is an example of a further kind – and by the time of the story a pattern for such a marriage had emerged. The bridegroom – wearing a wreath of flowers on his head, and accompanied by his male friends and relatives – led a procession to the home of his prospective bride. There, in front of the assembled guests who were the witnesses, a sort of contract was exchanged (originally a fictitious bill of sale between the father and the groom!). A short religious ceremony and sacrifice took place at the family altar, where the bride, dressed in a saffron veil with matching shoes, crowned with flowers and with her hair plaited in a symbolic way, took the bridegroom’s hand and uttered the marriage promise: ‘Where you are Gauis, I am Gaia.’ There was usually a feast, and then the bridegroom dragged his wife away – it was polite to show reluctance – to her new home, whose portals had been decked with greenery, and in order to avoid a stumble (which would have been a dreadful omen for their life) he picked her up and carried her inside. As the story suggests, the bridegroom usually scattered walnuts to the onlookers en route – a symbol of fertility and longevity.

All this pertains to Roman citizens, but many of the inhabitants of Britannia were not citizens at all and might come from a variety of tribes. Celtic traditions, languages and settlements remained, especially in the remoter country areas, but after two centuries most people had adopted Roman habits. Latin was the language of the educated, and Roman citizenship – with its legal, commercial and social status – the ambition of all.

However most common people lacked that distinction. Some were freemen or ‘freedmen’, scratching a precious living from trade or farm; thousands more were slaves, mere chattels of their masters with no more rights or status than any other domestic animal. Some slaves led pitiable lives, but others were highly regarded by their owners and might be treated well – like Pulchra in this story. Indeed a slave in a kindly household, certain of food and clothing in a comfortable home, might have a more enviable lot than many a poor freeman struggling to eke out an existence in a squalid hut.

The Romano–British background to this book has been derived from a wide variety of (sometimes contradictory) written and pictorial sources. However, although I have done my best to create an accurate picture, this remains a work of fiction and there is no claim to total academic authenticity. Commodus and Pertinax are historically attested, as is the existence and basic geography of Glevum (modern Gloucester).

Relata refero. Ne Iupiter quidem omnibus placet

. I only tell you what I heard. Jove himself can’t please everybody.

. I only tell you what I heard. Jove himself can’t please everybody.

One

The wedding of Pompeia Didia was an elaborate affair – not at all the sort of thing I usually attend. Anyone who was anyone in the colonia was likely to be there, and Glevum was founded for wealthy veterans, and was thus one of the richest towns in all Britannia. Not generally an event for humble slaves-turned-pavement-makers then, but His Excellence, my patron, had requested me to go – actually as his personal representative – and when Marcus Aurelius Septimus offers one an honour of that kind, it is not something that a man can readily decline – not if he hopes to live a long and happy life.

Of course, I was not expecting any such request so I was surprised early one morning to get a messenger at my home summoning me to come at once to Marcus’s country house which was only a mile or two from where my roundhouse was. I put on my toga, collected my young slave Minimus – himself on loan from my patron for a while – and set off at once. I was duly ushered into the

triclinium

, where I found him reclining on a dining couch, languidly nibbling a bowl of sugared figs – most unusual at this time of day.

triclinium

, where I found him reclining on a dining couch, languidly nibbling a bowl of sugared figs – most unusual at this time of day.

‘Ah, Libertus, my old friend!’ He waved a hand at me so I could kiss his ring.

I performed the usual obeisance rather cautiously. When Marcus greets me as ‘old friend’ like that, it is usually because there is some favour that he wants to ask. ‘You wanted to see me, Excellence?’ I said.

Other books

Stempenyu: A Jewish Romance by Sholem Aleichem, Hannah Berman

Sparring Partners by Leigh Morgan

Children of the Tide by Jon Redfern

His Perfect Wolf (Mystic Wolves Book 2) by Elle Boon

Rogue (Book 2) (The Omega Group) by Andrea Domanski

Bomb Girls--Britain's Secret Army by Jacky Hyams

The Gabble and Other Stories by Neal Asher

Cinderella in the Surf by Syms, Carly

Finish Me by Jones, EB

February Thaw by Tanya Huff