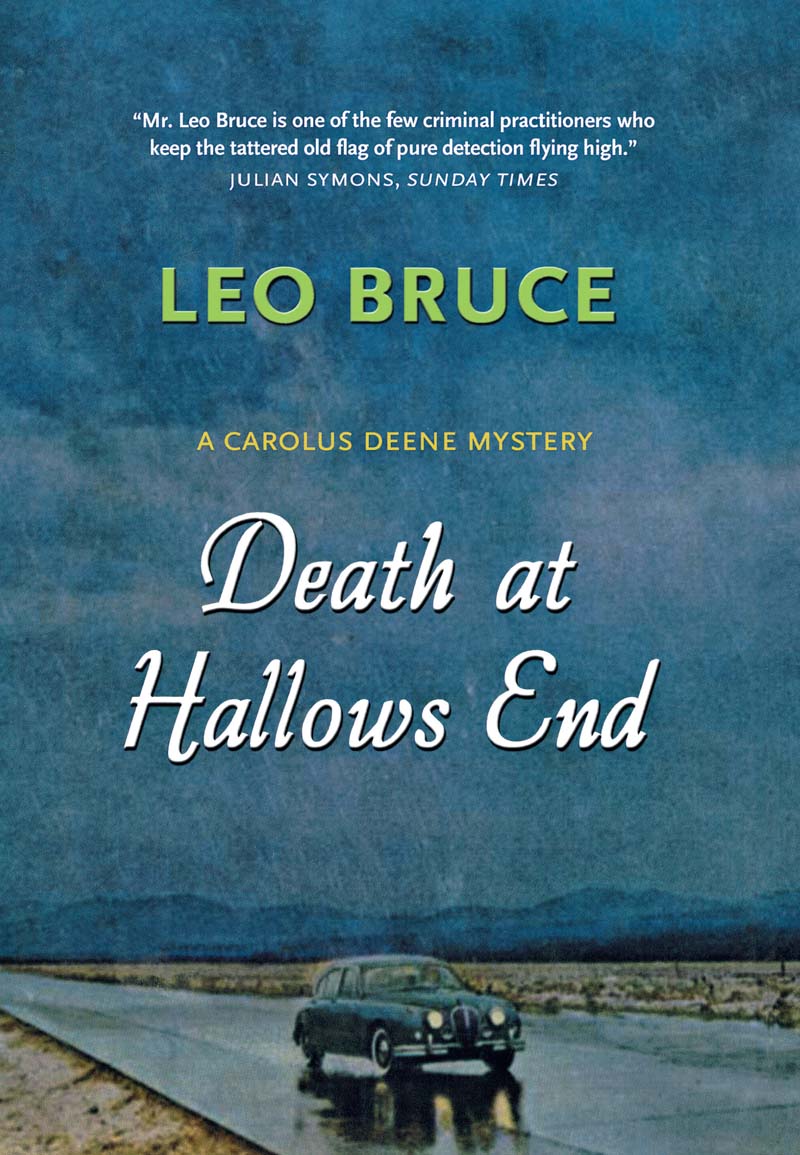

Death at Hallows End

Read Death at Hallows End Online

Authors: Leo Bruce

First US publication 2003 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

Published in England in 1965

© 1965 by Leo Bruce

Printed in Canada

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bruce, Leo, 1903-1980.

Death at Hallows End / Leo Bruce.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-89733-516-3 (hardcover)

I. Deene, Carolus (Fictitious character)-Fiction. 2. Inheritance and succession--Fiction. 3. History teachers--Fiction. 4. England--Fiction. I. Title.

PR6005.R673D38 2003

823'.912--dc21

2003001846

HAPTER

O

NE

“I

NTO THIN AIR,” FINISHED

Lionel Thripp, and leaned back as though he had effectively made his point.

It was not like this rather solemn solicitor to use such a melodramatic cliche, reflected Carolus Deene, but the circumstances were unusual.

“You've informed the police, of course.”

“Oh, the police. Yes, I've informed them and they tell me they have the matter in hand. But that's not much comfort to Theodora, who is beginning to fear the worst.”

Carolus, deep in a leather armchair in the solicitor's office, looked about him and thought it was an unlikely place in which to hear the rather startling story Thripp had just told. The firm was an old established one, so much so that the names of its two present partners, Duncan Humby and Lionel Thripp, were not among those in the firm's title, which was Merryweather, Priming and Catley. These, if they had ever been active in the firm's affairs, were lost in the Victorian past, and for thirty years no one but Humby and Thripp had sat behind the two mighty desks of the two inner offices.

Carolus had known both partners slightly for some yearsâthey were in fact his own solicitors, though his call today, made at Thripp's request, had nothing to do with his own affairs. He had just heard that for three days Duncan Humby had been

missing, and neither in his office nor in his household could anyone explain the fact. Some of the suggestions made by Thripp, in fact, came strangely from a staid solicitor and might have startled the inhabitants of the cathedral town of Newminster in which both he and Carolus lived and worked.

Carolus, however interested in facts given him, rarely made a written note but liked to get his details securely in his head.

“Just let us go over a few points again. You say Duncan Humby left here on Monday?”

“Yes. Immediately after lunch. He meant to return the same night.”

“He told you the object of his journey?”

“Yes. James Grossiter had sent for him.”

“He was going to Grossiter's home?”

“No. That was the first extraordinary thing. Old Grossiter was staying in this placeâHallows End.”

It was extraordinary. Everyone in Newminster had heard of Grossiter, who was reputed, in mouth-watering local stories, to be a millionaire. He lived in a gloomy great house on a hill overlooking the town, and rarely left it. He was usually called Old Grossiter, though he was not in fact much older than the man referring to him, Carolus reflected. Sixty-five at the most, but something of a recluse if not a misanthrope, and certainly a valetudinarian.

“He was a client of yours?”

“Of Duncan's, more precisely. He did not recognise my existence in the firm, perhaps because I joined it three years later than Duncan.”

“So he consulted Duncan?”

“I shouldn't say âconsulted'. To say he

instructed

Duncan might be better. As you know, he was an autocratic man and believed he knew a great deal about law. Duncan could handle him, I could not.”

“Did you know he had left his home?”

“Not till Monday morning when Duncan came in and told me that Grossiter phoned on Sunday from Hallows End.”

“What was he doing there?”

“That was the second extraordinary thing. He had gone to stay with his nephews who have some sort of a farm there.”

“Any reason for his visit?”

“He gave none to Duncan. But some months ago his son Raymond, whom he had quarrelled with, died in Cape Town. Old Grossiter used to say he would never actually make a will to help his son, but that he didn't care if his son inherited as next of kin. One gathers that he couldn't kill all paternal feelings in himself, though he refused to have any contact or correspondence with his son. The original quarrel had been connected with a woman Old Grossiter had employed. But Raymond Grossiter had afterwards married someone else.

“When he and his wife were killed in a car crash, Old Grossiter seems to have realised that unless he did something about it, all his money would be inherited by his sister's two sons, Holroyd and Cyril Neast, who had this farm at Hallows End. He scarcely knew them and decided, so Duncan believes and I agree with him, to investigate the pair. He may also have had it in mind to see a man named Hickmansworth. This was the illegitimate son of his second sister and thus a cousin to the Neasts. They farmed neighbouring properties. Grossiter went to Hallows End, without telling anyone, some days before his death.”

“How did the investigation go?

“One can only draw conclusions. On Sunday morning, at eleven-fifteen, he phoned Duncan at his home and told him immediately to draw up a will and bring it to him to sign on the following afternoon.”

“Do you know what the terms were to be?”

“Yes. As far as anyone did. His whole fortune, which was considerableâthough probably less than popular estimate has made itâwas to go to charities, except for five thousand pounds to his charwoman, a Mrs. Cupper.”

“Good gracious! What charities?”

“Any

charities, he told Duncan. Cat and dog homes, orphanages, anything Duncan liked, so long as absolutely nothing could be claimed by his nephews. We had quite a morning, drawing it up and making bequests to our own favourite causes.”

“I hope the animals were not forgotten?”

“They certainly were not. It was an interesting will. But there was one other point. When Grossiter gave Duncan these instructions on Sunday morning he added something which puzzled Duncan. He was to draw up an immediate Deed of Gift of ten thousand pounds to someone called Humphrey Spaull.”

“Did the name mean anything to you?”

“Not to me. But Duncan has an excellent memory. Soon after he started to act for Grossiter, some twenty-two years ago, there was a similar gift of about half that sum to a woman called Edith Spaull who had been Grossiter's housekeeper. Duncan said it was to set her up in a profitable little sweet-and-tobacconist shop here in Newminster.”

“I don't know it.”

“No. Mrs. Spaull died some years ago and the shop was taken over with some others by the East Street Supermarket. This Humphrey Spaull, whom we knew nothing about, was apparently the woman's son.”

“And did Duncan prepare this Deed of Gift?”

“He had not completed it when he set out on Monday. Grossiter emphasised that the will was the urgent thing. But Humphrey Spaull, whoever he is, would presumably have lost anyway, since it is almost too much to expect that the will was signed that afternoon before Duncan's disappearance.”

“Why?” asked Carolus. “Stranger things have happened. Duncan might have left his car and walked up to the farm, seen Grossiter and been obliged to ⦔

“Oh, yes,” said Thripp impatiently. “Everything's possible. But where is he now?”

Carolus was thoughtful.

“Meanwhile,” he said at last, “have you any reason to know whether the nephews were aware of that telephone call? That is, did they know they were being excluded from inheritance?”

“It would seem not. Old Grossiter distinctly said there was no one in the house when he phoned. The two brothers had gone to church, he said.”

“So it was with this will, all ready for signature, that Duncan left here on Monday.”

“Just so.”

“Did he go by car?”

“Of course. He drove his Jaguar. You know what Duncan wasâ

is

about cars. Motoring is still a hobby for him, though I must say I find it hard to understand. He and I are the same age, you know, and I've given up driving. But he still likes powerful motor-cars. He drives well, but I don't think he should speed as he does. That sort of thing could lead to a terrible accident.”

“But it did not in this case?”

“No. His car was found intact by the side of a quiet road which led to the Neasts' farm, the church and nothing much else.”

“You think he left it there?”

“It's hard to say. The keys of the car were left in it and the engine started at once when the police found it. There was no sign of any kind of struggle or anything of the sort.”

“And no sign of Duncan either?”

“None. As I told you, he seems to have vanished into thin air.”

“Yes. I noted the aptness of your quotation.”

“As you no doubt are aware, Old Grossiter died in the small hours of Tuesday morning. Coronary thrombosis. He is being cremated tomorrow.”

“Nothing questionable about his death?”

“Oh, nothing at all. The local doctor, an excellent fellow called Jayboard, has signed the certificate.”

“Then Duncan's disappearance at that point was extremely convenient for Grossiter's nephews?”

“Of course. They inherit. That is what makes Duncan's disappearance sinister as well as mysterious. If he had reached Grossiter in time they wouldn't have inherited anything at all.”

“Yet there is no reason to think they knew that Duncan was coming?”

“Unless in a fit of exasperation, the old man told them what he was going to do. He was a highly eccentric individual, as you know. Or unless by some remote chance someone remained hidden in the farmhouse on the Sunday morning and heard Grossiter phone.”

“So, not to mince matters, Thripp, your inference is that one or both of these brothers may have been involved in kidnapping or even killing Duncan Humby before he could reach Grossiter?”

“I wouldn't say it was my inference,” said Thripp cautiously, “but it does seem a possibility, doesn't it? What else can have happened to the poor chap?”

“I see what you mean, but there are several flaws in that, as even a provisional theory. Why did he stop his car at that point? Why did he get out of it without any sort of struggle?”

“He may not have stopped his car there. It may have been driven there after he had gotten out somewhere else.”

“True. But the whole idea becomes unreal when you consider that Grossiter died quite naturally that night. It introduces coincidence, in which I have no faith at all. For if as you suggest

the brothers prevented Duncan from reaching their uncle, Grossiter's death at that precise moment was too convenient altogether for them.”