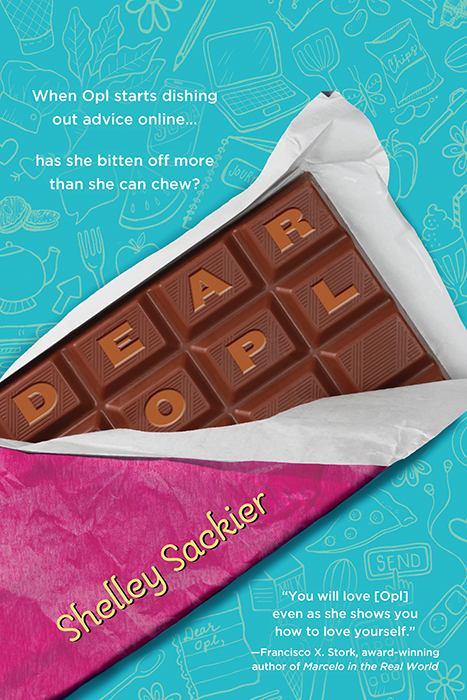

Dear Opl

Authors: Shelley Sackier

Thank you for purchasing this eBook

.

At Sourcebooks we believe one thing:

BOOKS CHANGE LIVES

.

We would love to invite you to receive exclusive rewards. Sign up now for VIP savings, bonus content, early access to new ideas we're developing, and sneak peeks at our hottest titles!

Happy reading

!

Copyright © 2015 by Shelley Sackier

Cover and internal design © 2015 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design and illustrations by Jeanine Henderson

Cover images © Lana Langlois/Thinkstock; fotyma/Thinkstock

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systemsâexcept in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviewsâwithout permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Jabberwocky, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

Source of Production: Versa Press, East Peoria, Illinois, USA

Date of Production: June 2015

Run Number: 5004259

To Chloe and Gabe, who for years told me that I didn't have to try so hard with my cooking. I forgive you. And you're welcome.

The dark enveloped me, squishing my lungs. Like the engulfing bear hug you get from an uncle who's built like a lumberjack. But this black was so tarry and thick, it made me feel as if I were breathing syrup and forced my heart to thud in my chest. I blinked again and again, and squinted hard, hoping somethingâ

anythingâ

would come into focus. I wanted to sprint for my bed, to hide beneath my quilt, where nothing but fuzzy warmth and an old licorice stick are allowed. But I needed this. I couldn't leave because I had to get rid of the awful ache that poked at my sleep. If I fed it, like a lion at the zoo, it would circle and grow quiet. Sometimes.

Even though I wasn't supposed to.

My hands fluttered in front of me, like a couple of blind butterflies. They bumped against a pointed edge. I jerked back, thinking I'd been bit, but I took a breath and crept forward until I touched it once more. I traced my skittish fingers along its form until I felt certain the thing wouldn't strike at me with sharpened fangs and light up with red demonic eyes. It was a box of cereal. And it had to be Froot Loops because the pantry was a bundle of lip-smacking scents like tangy lemon, zingy orange, electric lime, and mouth-watering cherry. This meant Ollie had left the bag open and steam would shoot out of Mom's ears because it'll have gone stale by morning. I sighed with relief because as far as I knew, no one has ever been seriously injured by sugary, ring-shaped cereal. Then, again, maybe my younger brother would be the first.

I pushed the box aside and moved my hands higher up. I knocked another smaller carton to the floor, where it bounced off my sock-covered foot. I squatted, sweeping my hands across the floorboards until I found it. Bringing the package to my nose, I sniffed its edges. It smelled like Thanksgivingâwell, not the last one, but the twelve others before that. It smelled of cinnamon and apples. It smelled of happiness.

I opened the box and felt inside, my fingers searching for more of the memory. They picked up a tiny pouch. A tea bag. It made the sound of Mom's old flower seed envelopes, the ones she held up each spring and shook like tiny maracas. “April showers bring May flowers! Let's go plant some future sunshine.”

That didn't happen this spring. Or the one before it.

I fumbled about until I found an empty spot I could push the tea bags into and then let my fingers wander farther across the shelf. They collided into something crinkly.

Bingo!

I pressed my hands around the package. It had the right soundâlike crunching plasticâwhen I squeezed it. I pulled it to my nose. Yes, definitely the right smell. And not one I could attach to any other thing. It was powdery sweet. Buttery. Not quite chocolate but deep, like cocoa. It mixed with scents of sugared vanillaâa cream so luscious, it ran slickly against your tongue. This was not just a food; it was a feeling. I wanted those Oreos so badly my mouth started watering like a mini sprinkler.

I felt around for the opening, the plastic pullback tab that granted you access right to the very heart of the package and the cure-all cookies. Tonight's remedy. But something was wrong. The pull tab was missing. I groped the front and back, skimming its sides, trying to catch the sticky edge like you do when your Scotch tape has come off the metal ridge and sealed itself back onto the roll. It wasn't there. I couldn't find it.

Something brushed against my cheek and I reeled back in fright, bumping into the rickety pantry steps behind me. My fingers slapped at my face, but found only my hair falling out of its messy ponytail. With a racing heartbeat, I ventured a hand along the wall, searching for the light switch. Then I pulled back. I'd better not turn on the pantry bulb, because the glow would creep down the hall and shine like a headlight through Mom's open bedroom door. She was a super light sleeper. She could leap out of bed at the sound of a cricket passing gas on the back porch.

But I needed those cookies.

A flashlight! That's the answer. I bent down to hunt the lower shelf beneath the microwave. In my mind I could see four of them on the ledge, lined up like eager soldiers: sentries of the dark. But I bumped into one and they tumbled like dominos. I held my breath, trying to absorb the clunking sounds. I made that lungful stay put and listened, wishing I had a third ear. At the relief of no footsteps rushing into the kitchen, I grasped one of the tipsy warriors against the dark, flipped its switch, and looked at the package in my other hand. I held the Oreos all right, but they'd been double packaged, slipped inside a Ziploc bag along with a folded piece of stationery.

I sat down on the old wine crate Mom used as a step, forgetting about how badly it creaked, and unzipped the plastic bag. I pulled out the note and tilted the beam toward the words. It said:

Dear Opal,

Please don't eat these. Remember your diet.

I love you,

Mom

An opal is a mineral. Not many folks know what color they are. Even opals are confused over that. They're basically colorless. It's all the impurities inside themâthe gunkâthat makes them whatever color they end up.

An opal isn't as ugly as a chunk of coal, which some people say is a mineral, but isn't really. You'd get that wrong on a science test. But it isn't as impressive as a diamond either. It can't compete in that world. Diamond advertisements scream,

You

are

loved!

If you get an opal as a present its message is sort of,

Will

this

do?

My name is Opal, but I don't spell it that way. It now looks like this: OPL. I kicked out the A. I figure if Mom wants me to lose weight, maybe she'd perk up if at least my name shrunk by twenty-five percent. And even though opals come in every color of the rainbow, the regular ones, just like the inside of an Oreo, are flat and doughy. They're called

potch

. If I had to compare myself to any opal, I wouldn't be the rare, fiery red ones or the super expensive black ones. I'd be potch. Chalky white and kind of pasty. And with a lot of gunk inside. I've grown into my name. But I didn't need the cruel reminder every time I put it at the top of a spelling test.

I guess I'm lucky it's not something like feldspar or zircon or crapolite. Okay, that last one I made up, except it's pretty close. That one describes more how I feel. At thirteen, there are a lot of things that suck about being me, but the biggest thing is the thing that's making me big.

Food.

I'm food fighting. And not in the fun way. I'm not lobbing spoonfuls of mashed potatoes across the cafeteria. My battles are more with myself. Okay, and maybe Mom. Yeah, if I could hurl the mashed up mush at anybody, I'd aim at her. All she sees when she looks at me is food anyway. I'm a giant lollipop she wants to draw a red circle around and put a jagged slash through. Banned. Unwanted. Yucky.

“I've been thinking, Opal. Why don't you start a blog?” Mom said in her

I

am

really

trying

to

be

positive

happy voice the morning after my midnight cookie raid. “Maybe to keep an inventory of what you're eating. It could be a Bread and Butter blog.” She poured coffee into a thermos, taking her time, a tiny stream from the pot to the cup. Right beside her thermos was the Oreo bag, on display for the whole world to see. She refused to look me in the eye, and her suggestion of the blog must have been my pantry punishment. “I think it'll be easier if you kept track of things, like you do with your mittens or homework.”

“Or how long it takes you to pour a cup of coffee, and how many times we get to talk about food,” I mumbled so she wouldn't hear. But I wanted her to hear. Especially how much I wanted to

stop

talking

about

food

.

“You can write about anything you want, as long as it helps you stick to your promise,” Mom said, finally screwing on the thermos cap and then grabbing an armload of crumpled, messy papers before dashing out the front door with a careless wave. Dashing off to a place where everything is easier. Where work comes first and family troubles get buried. If I got to work in a library, I'd probably find it super easy to ditch my difficulties too. I bet she just reads all day about other people's happy times. I know I would.

I plopped two “against the rules” Pop-Tarts into the toaster and pushed the lever down hard. I leaned over to watch the coils blaze and turn bright orange. Waves of heat reached my face. Maybe it could melt away my fat, like butter in a skillet.

I heard G-pa's slippers swish along the kitchen floor and stop at the electric tea kettle. Neither of us said anything because we're not exactly morning people, but after my pastries popped up, I stopped at the counter where his mug of tea steeped.

G-pa came to live here after Dad left us. He set up his station in the corner of the living room. All he needed was a big stuffed armchair, an ottoman roomy enough for his feet and for me to perch on, and a little side table for his stinky tea.

“What are you drinking today?” I asked him.

“Japanese tea,” he said, his voice still crusty from sleep.

“What's in it?” I looked down at the mug.

“Smell it.”

I did and felt my nose shrivel up inside itself. “Ick. It smells like twigs.”

“Then your nose is off,” he said after a sip. “It's roasted twigs.”

I pinched my nose and eyes together, squeezing everything into one space. He'd think I was making a face about his tea, but I was actually trying to keep from cracking up. I didn't want G-pa to know I thought he was funny. Because then he might stop trying to make me laugh. It was our contest. And I wasn't ready for it to be over.

I moved away to the kitchen table and put my Pop-Tarts next to my open laptop. I tucked my earbuds in and tapped on my favorite morning playlist. Then I thought about Mom's last words.

You

can

write

about

anything

you

want, as long as it helps you stick to your promise

.

But Mom had said the same thing when she gave me the journal with the purple, wavy psychedelic cover. And the old electric typewriter that punched a hole in the paper anytime I used the letter Y. It was as if that key was super hyper and on a Red Bull diet. Or maybe it only wanted me to pay attention to the words

candy

or

Dairy

Queen

or

mayonnaise

.

When journaling didn't take, Mom had plastered the refrigerator door with before and after pictures of skinny women in swimsuits.

She had said, “It's hard for a person to commit to change, Opal, but if you feel like you aren't alone in the battle, it lightens the load.”

I had studied the pictures with a magnifying glass. Those women weren't even human because our science book says we have twelve ribs. I could count all of theirs, and I never got past nine.

After Mom went to bed, I'd usually sneak downstairs in my double thick hiking socks. They have yet to go hiking, but it's like wearing pillows on your feet. No one hears you coming. Not even the pretend women on the fridge. Then I'd fill a jumbo blue mixing bowl with Frosted Flakes, muffling the sound as much as I could, sprinkle it with Nesquik, and drench it with chocolate milk. Somehow it filled the hole. Made me less see-through. Even for just a little bit.

Finally, she bought me a laptop. “You can take it anywhere, Opal: in the car, in your room, and most importantly, in the kitchen. You can track everything you're eating. That will be an eye-opener. It can be a Junk Food Journal.”

“How about a Waste of Time Diary?” I snapped. If she could come up with a new nickname for this crummy catalogue idea every day, then so could I.

“Sure,” she had said, staring at the chaos on her desk. Her hand waved in the air toward me, as if she were reaching for something in the dark. “Whatever will keep you on the right track.”

The

right

track

, according to Mom, will finally allow her to buy me a pair of skinny jeans. I don't want skinny jeans. I want sweat pants. Jeans are so uncomfortable with the rough fabric, the tight waistband, and no room to balloon when my stomach bloats. Once I zip them up, whatever can't fit inside pops out and rests on top, spilling over like cake batter in a bowl too small.

What really bothers me is that if I do as Mom wantsâif I manage to finally get myself into a pair of skinny jeansâI'd disappear in front of her. No more Opl. Trouble fixed. I'm a problem not a person. But Dad was a problem she couldn't fix, and he disappeared from our lives too. It feels like we're all on our way to disappearing in front of Mom. Maybe that's what she wants.

Poof.

And why are we still wearing jeans anyway? It's an outdated material made for California gold miners. I live in Virginia, in a town that won't let you chip away at anything because one of our dead presidents may have walked on it or leaned against it. Plus, mining is not in the school's curriculum, so why should I dress like I'm nugget hunting? Unless they're McNuggets. Still, buying those pants neared the top of Mom's nonstop to-do list. But getting me into them was nearer.

I broke off a chunk of my Pop-Tart and flung it at Mr. Muttonchops, our dog. He raised his hairy head just in time to snatch it out of the air, swallow it whole, and resettle himself beneath the bridge G-pa made with his legs up on the ottoman. G-pa raised one furry, white eyebrow at me.

“He's helping me with my new diet,” I said, shrugging.

G-pa went back to tapping on his tiny laptop, which he was still trying to get the hang of using. He said he figured if he wanted to talk to me or my little brother, Ollie, then he'd have better luck emailing us rather than shouting to get our attention, since we are glued to our computer screens with our earbuds in. I've told him a hundred times that he has the Caps Lock button on, but he doesn't seem too fussed. Most of what G-pa says is extra loud anyway.

G-pa and Ollie were the only people on my side. They knew how hard I struggled to pass up a second helping of dinner. According to Mom,

portion

control

was my number one enemy. According to G-pa, Mom slid into second place.

SHE'S BIG INTO SETTING GOALS NOW. YOU'RE ONE OF HER PROJECTS.

G-pa's email showed up on my laptop, sent from across the room. He must have heard Mom and me in the kitchen before he'd come in for his tea.

I looked up at him. He shook his head.

In fact, he must have kept his head shaking the whole day long while I was at school because at suppertime he was still doing it, only now it was over something even more ridiculous. G-pa absorbed everything that went on in our house from his chair. And spat out the stuff he thought was bunk. He thinks people talk too much, that they use fancy language to scare you into quiet.

SAY

WHAT

YOU

MEAN. DON'T WASTE WORDS

, he'd emailed after hearing me try to tell Mom I wasn't a big fan of fat-free potato chips.

That's another of my problems. Not only did I gulp down a lot of food, but I swallowed stuff I wanted to say. Telling people what you really think is a surefire way to bring on sour faces. And ever since Dad's been gone, I've seen nearly two years' worth of faces in this family that range from salt-crusted to bitter.

TAKE

A

PAGE

FROM

OLLIE'S BOOK. HE DOESN'T GIVE A RIP WHAT PEOPLE THINK.

G-pa was right. Ollie was six and wore mostly old Halloween costumes. All of them meant for girls. He'd started this habit once Dad left us. And by left us, I mean died. I just refuse to put it that way.

It was quick. And came as a big surprise. Even to Dad. One minute we were carving pumpkins on the kitchen table, and the next he got really sick and was holding my hand in his hospital bed saying,

Everything

happens

for

a

reason

.

But his doctors sure didn't have one that made sense to me.

He used to tell us that there was nothing he wouldn't eat, but suddenly there was nothing he

could

eat. He said everything the hospital made tasted bad and he wasn't hungry. Mom would bring in food, but I knew he wasn't eating it. I tried helping himâthe way he used to help Ollieâby me taking a bite and then trying to get him to take one. I ended up eating Dad's bites too because it made me feel like I could help him not slip away. His cancer was a lot hungrier than he was. I'm glad that Ollie doesn't remember much. I think we'd have a heck of a lot more than just his wearing of girls' costumes to worry about.

Tonight, Ollie came down the stairs to the dinner table dressed as either Lady Gaga, an ER nurse, or a distressed Disney maidenâit was hard to tell, but it sure made Mom's face pinch up.

“It's just a phase,” she said to G-pa. “He's lacking a good male role model.”

G-pa quickly emailed me,

THIS

PROVES

I

SHOULD

BELCH

AND

SWEAR

MORE

.

I looked up from my computer and gave him one of the sour-pickle faces.

Ollie started acting super practical about my

situation

as Mom liked to call it. “I think if you're hungry, you should eat.” He plucked the Pillsbury biscuit off his plate and plopped it on mine. I wanted to squish him with a hug. Instead, I glanced over my shoulder to see if Mom saw, but her eyes stayed glued to the mess on her desk. I wondered if her forbidden food radar would kick in.