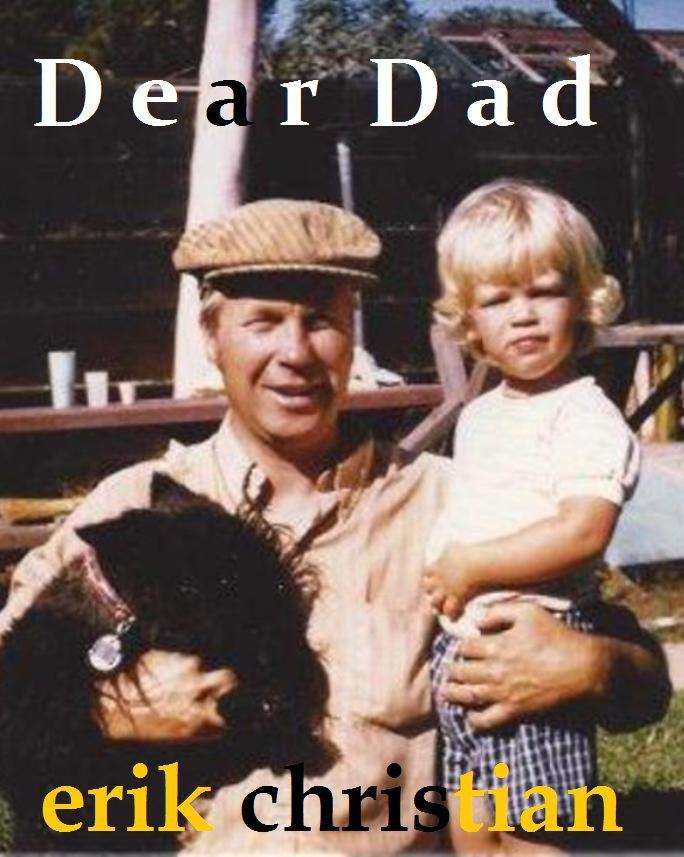

Dear Dad

Authors: Erik Christian

WE WERE TIMID

We were timid. My sister and I. We hid when the doorbell rang. I remember hiding behind this large tropical potted plant in the entrance frozen with fear. My sister looked over at me, as if it were just a game of hide and seek. There were a lot of fears in being a small boy living in Southern California. At night while in bed, trying not to wet my pants, but too bloated to walk to the bathroom, I sat as still as a sardine while the spotlight of patrolling helicopters hovered above. The light canvassed our yard like a flash from Heaven, revealing my death and birth in a moment of delirium. My parents were new at being parents and our home was small, lodged in between avocado and orange trees and nestled between a busy side street and a mysteriously dark alleyway. The alleyway held all my dark and fearful creations that didn’t exist. After dark, the alleyway was off limits and was shut out by the light from inside over the dinner table.

I had just started Kindergarten and don’t recall anything out of the ordinary except for Parade day. Since everything my parents did for my sister and I was sheltering us from harm, this inevitably bled over to the sheltering of the realities of regular life. There was a parade happening by my school one day and the teachers thought it would be fun to run out and watch it. I stood next to a girl, probably the first unrelated girl I had been near, and awaited the horns and drums and the pumped up cheerleaders. I remember looking over at the girl a lot and she would smile. In my mind, we were already friends and maybe more. The band approached and in slow motion my cool demeanor for the girl turned into absolute fear of the sound of the cracking snare drums. It was like firecrackers in tin cans. I watched her face turn from a smile of the best sweetness of smiles to this look of concern and worry. I was letting her down, dropping the ball on my confidence and pride and wrecking our courtship. I let it all loose as if being defiant with my full bladder at night and realizing there was no hope for a bathroom visit and just letting go. Isn’t everything letting go, restoring the damages and delusions of youth at an older age? I was crying and the snare drums and bass drums were pounding and no one noticed anything wrong, especially tears coming from a little face in a crowd. But the girl did and eventually the teachers did.

One day after school, I got onto the large school bus that took us home. I noticed the driver was not the same laughing potbelly guy. I walked past him without saying anything. As the bus route unfolded, the little occupants became few and less. I was getting to be the last one. The driver was talking but I couldn’t hear, so I walked all the way up the shiny dark blue linoleum aisle. The large glass bulb lights on his dashboard mesmerized me. I loved little lights that indicated something I didn’t understand. I finally realized that the bus driver was asking where I lived. I was only five and had trouble at first formulating a verbal map for the potbelly-less, unlaughing new driver. After a few minutes of not knowing how to speak for myself, I finally sprouted a knowledge, a wealth of unused words that the driver could understand. I saw my words change his facial expression and move his eyebrows like slot machine numbers. I was doing something to him with my words. The bus began to get onto familiar streets and I got increasingly excited. I spoke faster as the driver drove faster and soon there was the corner where I scraped my knee really bad and then the dark and mysterious alleyway, which wasn’t mysterious at all during the day, just two stupid garbage cans and my life became clear as the air breaks of the bus hissed and the bus driver finally smiled and I smiled and I thanked him and we were now friends and I walked through the front door of our house which I never did and felt hungry and alive.

THE FORGOTTEN SOLDIER

I didn’t really fit in. A lot of people say this, even though they had tons of friends. They’re just trying to emphasize. I kept to myself but with a longing to communicate and be heard. The fantasies of being the most popular or outspoken were plaguing. Everyday I watched the clock on the wall in class. When it hit Three o’ clock, I ran for the door. My friends were mostly on Television. Facts of Life and Different Strokes were my favorite, then Three’s Company. Their bond was tight and I could join in the fun and laugh along with Jack Tripper as he goosed the girls. I felt all the emotions they conveyed on screen as I ate Fig Newtons on the cozy family couch till dinner time. I was engrossed with Television and soaked in all the social cues that enabled me to function in my own life. I was an empty shell off my mother’s assembly line womb, and color filled into my cheeks with the first laugh of a sitcom.

I began flunking classes my Freshman year. The first in line was English. Barb Myers was a horrendous woman who fostered a brown-nosing requirement, and the front row of her classes always had the top brown nosers, who raised their hands for everything and stayed after class to help Myers out with extra curricular activities. I was always in the back row with the other two rejects. I was king of the rejects and protected them as much as I could. One day, Miss Myers told one of the rejects to leave the class. She then said under her breath to the rest of the class, “It’s like talking to a marshmallow.” The brown nosers laughed uproariously. That gave me enough ammo to take to the principal’s office and report her. Unfortunately, my clout was less than hers, so nothing was done.

My Junior year came and our marching band class was to travel to a Ocean side destination to relax, as a reward for being a great group. I liked the class because I had switched from Trumpet to drums and enjoyed hitting things. The only other class I enjoyed was Metal Shop, because I could watch metal slowly melt by my hand with a torch. I could get a ball of melted metal on the end of the welding rod and flick it across the welding shop. It would explode into sparks on the cement floor a hundred feet away. That class was a fucking war zone! Anyways, Marching Band was off to Ocean Shores. Something happened to me on that trip. Maybe it was the feeling of travel, or the essence of leaving something behind, but I began to open up. I began to joke around and make funny noises. The other kids who used to ignore me began to turn their ears towards me and laugh. Soon, most of the people on the bus were watching me as I spoke with a newfound sense of freedom, imagination & confidence. It was like I was in a coma for most of school and that day was the catalyst for all the beautiful, witty banter ahead of me. We arrived at the ocean and we kicked the sand and laughed and ran with the wind and the seagulls. The girl I had a crush on for years was looking over at me. It was all coming together because I let go.

When the trip was over and Monday began and it was class as usual, I felt the confines of normalcy approach like a dark cloud over a cement pour. My laughter subsided and most of the class soon forgot about my blossoming experience. Ten years later though, there’s still two or three people that remember me and that day and mention it to me with a smile.

SAILING AWAY FROM MYSELF

Growing up, I was subjected to my dad’s all-consuming interests in passing waves of fad. One fad that stuck that wasn’t really a fad, but a hobby that took years to die off, was sailing. We lived in Newport Beach, California and the waves were always enticing the locals to surf them, and the tourists to watch them. My dad had bought a fiberglass hull, and when he wasn’t putting in eight to twelve hours a day at the telephone company, fixing phones for people like John Wayne, he was cutting jigsaw pieces of teak and creating a masterfully crafted interior inside the boat. The boat was a huge eye sore in the neighborhood, with the boat peeking over the fence and grabbing peoples’ attention. My dad’s passion was unknown to me. I was only four and cared only about my next meal and my nap. The day my dad had saved enough money to buy the brand new little silver diesel boat engine, made somewhere Swiss, was an event years in the making and half the neighborhood came over with six packs of beer and watched the giant hired crane lift the engine off the ground and into the boat’s belly. They had to take down part of the fence to do this, as they had to remove the fence for the mast and finally for the boat’s journey to the harbor. Young skinny guys in white T-shirts stood around my dad and laughed and listened to him. I guess my dad was a local hero of sorts.

When my mom held the thick glass champagne bottle, ready to christen the boat, she had mentally walked through the procedure of hitting the boat hard enough with the bottle to break it. It was a big day, five years to the day for this boat and two years for the second. We have some pictures in the family photo album, if I fanned them out on the carpet, would show a slide show of my mom hitting the boat, like Babe Ruth hitting a baseball, with glass flying towards the water like ice flying off of a truck’s windshield. That day marked the anniversary of my terror of boats for the next ten years.

My Dad had to fulfill some part of manhood or an adrenal gland deficiency by sailing to the extreme. That meant keeling the boat over to the point of flipping, I thought. We sailed hard, capturing every wind gust that promised a few miles of great back draft and white capped waves that peeled off the hull like waves of whipped cream. Of course I was on the railing, holding on for dear life and crying as loud as I could to get my dad’s attention over the sound of the rippling sails. I could see he was loving this newfound freedom of sailing. I could slow the movie down in my mind and put a cheesy Bee Gees song to it and it would be the sailing version of “Chariots of Fire”. He was engrossed and I was seasick and later it became something else between He and I, but for this moment it was holding down my sickness. I wailed on and heard the dishes in the Galley crash to the floor as my mom’s beautiful red hair flicked in the wind and a look of complete serenity passed my parents’ faces.

What I loved most were the times when there was no wind and they had to turn on the motor. The sound of the engine rumbling and knocking and vibrating through the sunny, warm teak deck was bliss. I would place my ear down onto the deck like a suction cup and the engine would lull me to sleep, very deep sleep. Saliva always dribbled over my pudgy lips and created a pool. I slept for hours and even slept during a trip to the San Juan Islands, which took four hours at least. I’d like to think that my mind was working on my future during these times, that I was creating Mozart symphonies and Van Gogh art, or at least forming a genius of my own, subconsciously. That diesel engine led to my preference of always sleeping with “white noise”. There’s a giant fan in my room now. It blows through my room and the sound elevates me above the surrounding reality of traffic noise and branches snapping from under deer’s hooves. I feel stifled without white noise. I feel caged, like being an Indian on a Reservation, when they’re meant to roam the land and hunt buffalo. Now, they just get fucking drunk.