Dean and Me: A Love Story (6 page)

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

“Where’s a pen?” I yelled. Funny guy. Dean looked pretty excited, too. But once again Greshler, who was standing by, prevailed.

“The boys are booked at Slapsy Maxie’s”—a famous Los Angeles nightclub—“in late August,” our agent told Wallis. “We’d love to sit down and talk with you then.”

Wallis smiled politely—looking not especially pleased that he hadn’t gotten his way on the spot—and said he looked forward to it.

“What were you thinking?” we wailed to Greshler after Wallis left. “Hollywood comes calling, and you send it packing?”

“You think he’s the only fish in the sea?” Greshler said. “You watch—they’ll all come courting.”

Once again, he turned out to be right. And though what resulted wasn’t a shotgun marriage, in the end it might as well have been.

CHAPTER FOUR

THE DAY WE ARRIVED IN LOS ANGELES—AUGUST 9, 1948— our new press agent, Jack Keller, took us to George Raft’s house for our first Hollywood party. George

Raft

! My eyes were practically falling out of my head. My God, Raft was the biggest movie star in the world (or at least the biggest one I’d ever met), and here he was in his cabana, telling me to pick out a pair of brand-new swim trunks and go jump into his gorgeous backyard pool. I suited up and ran out to Dean—who was standing poolside, cool as could be, with Loretta Young, Sonny Tufts, Edward G. Robinson, Veronica Lake, Mona Freeman, William Holden, William Demarest, and Dorothy Lamour. . . . All big, big names of the day. I tapped my partner on the shoulder and—I couldn’t help myself— screamed, “Now,

this

is show business!” Despite his blasé appearance, I knew Dean couldn’t have agreed with me more. He idolized Raft, who’d had a rough background similar to his own. As a kid, he’d seen every movie the tough-guy actor ever made.

As the sun set, Keller came by Raft’s house to pick us up for our press conference at the Brown Derby. When we got there, we met the queen of gossip columnists, Louella Parsons, aka The Headhunter from Hearst. She spoke like a Muppet without a hand up her back. As she interviewed us, she wrote on a little pad given to her by the Shah of Iran during a polo match at the Will Rogers estate in Pacific Palisades on a hot summer day when Clark Gable was sitting on a horse but couldn’t get a game.... We found all this out because we asked, “Where did you get the cute pad?”

Lolly Parsons may have sounded like Betty Boop, but she wielded a lot of power. She was the Big Mamoo, the Chief, the Ultimate Journalist. Give me a break. She was an old, fat has-been who couldn’t make it in Hollywood, so she made it with everyone she could, including William Randolph Hearst. She’d tried acting and flunked, and Mr. Hearst needed a spy to live in the underbrush of Hollywood and tell him all the stuff that eccentric old men need to hear, so poof! She was a columnist.

At the press conference, Lolly tried to take us down a peg. Sure, we’d been a hit in New York, but Hollywood was a very different place, she told us. From the outset, though, I made it clear that I wasn’t about to kneel before her. “We’ll be an even bigger hit here,” I predicted flatly. Lolly made a face like she’d bitten a lemon. I was always outspoken and honest with her, and would eventually get in deep trouble because of it. Later Keller said, “If you think of the cosmos, we are but sand on a world of beaches . . . we almost mean nothing when you count it all. What are you trying to be? The conscience of the world of show business? Wise up, sonny. They won’t hear you, but I love that you try!”

At the Brown Derby, Dean whispered to me, “Please, don’t flag-wave. We’re lucky we’re here!”

I said, “We’re not lucky! We’re good at what we do, and don’t ever forget that.” Then I made the face of a little kid who has just spoken out of turn. . . .

That night we opened at Slapsy Maxie’s, on the Miracle Mile—Wilshire Boulevard between Fairfax and La Brea. After all the publicity about these two crazy people, the Crooner and the Monkey, every big shot in town had come to watch.

It was an era when all the stars went out at night—to dance and dine, to see and be seen. Los Angeles was a city of fabulous nightclubs: Ciro’s, Mocambo, Trocadero. But the biggest, poshest, most fashionable club in L.A. was Slapsy Maxie’s. The ringside was huge—it looked like 180 degrees when you were standing at the center of that great stage. And at the tables were (get a load of this): Barbara Stanwyck, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Jane Wyman, Ronald Reagan, James Cagney, Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Donald O’Connor, Debbie Reynolds, Gene Kelly, Fred Astaire, Rita Hayworth, Orson Welles, The Marx Brothers (the important ones: Harpo and Chico), Edward G. Robinson, Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Carmen Miranda, Al Jolson, Mel Tormé, Count Basie, the whole “Metro” group, including Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, not to mention Greer Garson, Spencer Tracy, William Powell, Billy Wilder, June Allyson, and Gloria De Haven (more about these last two soon)....

Keller was outside our dressing room, announcing every name as they entered the club—names that could not only excite but make you shake with fear. . . . And we were about to go out there in front of all those people and do our stuff.

I looked at Dean a moment, and he saw the question in my eyes. I never said a word, though I wanted to ask, “Are we good enough?”

And he smiled at me as only he could smile, and in his eyes I saw my answer: “We’re fine! We’ll be a smash!”

And we were. Oh, were we a smash. We tore that goddamn place down.

The day after our opening at Slapsy Maxie’s, the studios came calling.

We had an initial meeting with Jack Warner, who delighted in doing his own stand-up and clearly would rather have gotten a laugh with a joke he’d heard from a grip or an electrician than sign a new twenty-year deal with Bette Davis.

Then we got a call asking us to meet with the great Louis B. Mayer himself, at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios in Culver City. After taking the famous Long Walk—everyone in Hollywood knew about that intimidating corridor that led to Mayer’s office—we were ushered in by two security guards, one on Dean and one on me. The office was known as Mayer’s Folly, and when I saw the layout, I understood why.

We were asked to sit in two chairs carefully placed before Mr. Mayer’s desk—close enough for him to shake our hands. Although he wasn’t a tall man, he was looking down on us, as if we were two street urchins. I kept staring around the huge office, and it soon became evident to me that Mayer was sitting on a platform. It was subtle, but he was definitely sitting higher up than the two of us—an ingenious device that made him the prophet and all those sitting before him the disciples. A great device for him and his need to dominate.... But as young as I was, I could still smell a rat.

We sat and listened politely as he told us his life story: how he’d started from nothing, come west, and built this studio . . . and now he was L. B. Mayer! When he took his first breath from the dissertation and made us an offer for forty thousand dollars a picture—with MGM’s ironclad control over all our outside work—I wanted so much to say, “And you’re still nothing.” But because I was afraid Dean might slash my throat, instead I said, “Mr. Mayer, we would like to sleep on your offer and get back to you.”

Mayer didn’t look happy. “No one out there will better my deal!” he shouted.

Both Dean and I half-smiled. We got up, made that interminable walk to the door, and, as if we had rehearsed it, both turned and waved heartily....

(We later found out that after we’d left, Mayer had delivered the immortal pronouncement: “The guinea’s not bad, but what do I do with the monkey?”)

When we arrived back at our hotel, there was a message to call our agent. Dean made the call. I made a malted—the only true sustenance I gave my body in those days. I was just too excited about everything that was happening to us to eat anything else. My partner, on the other hand, had a six-course dinner every night, without fail. I’d say to him, “Eat, my boy, build yourself up so you can continue to carry the Jew.”

Dean, on the phone with Greshler, was doing all the listening. I heard nothing after the first hello. He finally said, “Okay, Abby, I’ll tell Jerry. He’ll like that a lot.” Then he hung up and, to drive me crazy, stuck a cigarette in his mouth and proceeded to look all over the suite for a match.

I knew what he was up to, but I bit anyway. “Tell me already, you lousy fink,” I said. “And use the goddamn lighter in your pants pocket.”

He sat on the edge of the bed, grinning. “Abby says he’s not really interested in the Mayer meeting,” he told me. “He says we can do better.”

When we sat down with Greshler, he told us that Universal had offered us thirty thousand dollars a picture. Twentieth Century Fox offered a little less, but for a six-picture deal. Sam Goldwyn wanted us as a team, but with the option to split us up when a project called for either a handsome leading man or a crazy Jewish monkey. Republic wanted to make a film with us, but basically wanted to shoot our act in a nightclub. (An interesting idea—in hindsight!) United Artists thought we’d be good in a remake of

Of Mice and Men

. Columbia, in the person of the notorious Harry Cohn, told Abby Greshler we were nothing more than The Three Stooges, minus one. Warner Brothers offered us the most money—but only if we signed for a seven-year deal.

Finally, our agent mentioned the one studio I’d silently prayed we would hear from—Paramount.

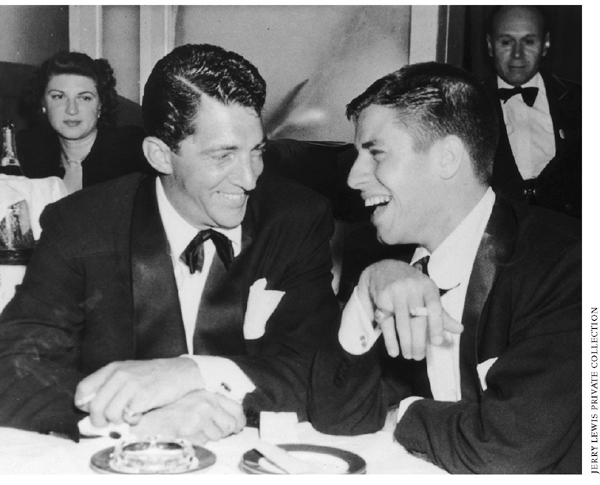

First tux: Chicago was never handsomer.

Hal Wallis, the producer who’d come on so strong in our dressing room at the Copa, was back with a serious offer: fifty thousand a picture to start with, working up to a ceiling of $1.25 million a film over the next five years. The money sounded good. But I told Dean and Greshler that for me there was a lot more to it than money.

For about a year, when I was seventeen and eighteen, I’d worked as an usher at the Paramount Theater in New York, the site of Frank Sinatra’s first great triumph in the early forties. And so I had a sentimental feeling about Paramount, but it was more than sentiment. While I was ushering, I had the chance to see the studio’s in-house promotional films, which showed the stars on the lot, the sound stages, the art department, the camera department, the wardrobe and makeup departments, the stars’ dressing rooms, the commissary, and—most fascinating to me—the editing room. Wow! I thought Paramount was just the greatest studio of them all, the best of the best. That name! Those stars ... W. C. Fields, Gary Cooper, The Marx Brothers, Mae West, Claudette Colbert, William Powell...

“A lot of people have serious money on the table,” Greshler reminded us. “I can go back to Mayer. . . .”

“Let’s go with Paramount,” Dean said.

Greshler said, “You’re sure?”

“My partner’s sure,” Dean told him.

When Dean and I signed to make movies with Hal Wallis and Paramount, I thought all our troubles were over. Little did I know they were only beginning.

After all, becoming a movie star is the American dream, right? Sign on the dotted line; fame and riches follow! Well, the movies would bring us a ton more money; they would spread our fame around the world. But they would never take us to the artistic heights we achieved in live performance: in clubs, theaters, and on television (much of early TV was broadcast live).

Why was that?

When my partner and I got up in front of an audience, any audience, we and they knew that at any minute absolutely anything could happen. Our wildness, our unpredictability, were a big part of the package. It was thrilling to an audience that we could do all the mischievous things they might imagine but would never really do.

This was only half of it, though.

The other half was that indefinable something I’ve talked about: our obvious pleasure in performing together. Audiences have a great desire to

feel along with

their favorite performers. Dean and I had an uncanny ability to get an audience to not just be viewers but to participate in our fun.

In films it wasn’t as easy to generate those feelings. In fact, it was damn near impossible. After all, the pleasure of movies is not in spontaneity but in story. Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy and girl get back together. Three acts—that structure is as old as the hills. But there are parts of the human spirit that three acts can leave out.

For his first project with Martin and Lewis, Hal Wallis had decided to try a low-risk proposition: plugging us into a low-budget movie project he’d already started. The picture, called

My Friend Irma

, was to be based on a popular radio series of the same name, about a ditzy Manhattan career girl, Irma (played by Marie Wilson), her best friend Jane (played by Diana Lynn), and their adventures. The series had been created by Cy Howard, who had also written the screenplay. With a little revision, Wallis thought, Dean and I could be plugged into the script as Irma and Jane’s boyfriends.

So he thought.

It felt like Fantasyland when the two of us were ushered onto the Paramount lot for our initial meetings with studio brass and our director-to-be, George Marshall. Mr. Marshall, who had directed W. C. Fields in

You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man

and Bob Hope in

Monsieur Beaucaire

, was not only a terrific filmmaker but a wonderful person (and, ultimately, a dear friend and confidant). He was to direct us in our screen test first thing the next morning.

The 5:30 A.M. wake-up call came as something of a shock: Normally, that hour was one my partner and I only saw when we were turning in! For the first time, we began to realize what moviemaking held in store for us. Shooting generally begins around nine in the morning, but with travel, breakfast, makeup, and wardrobe, you’d better get rolling at half past five or you’ll have a couple of dozen people understandably pissed. So we learned right away that being on time was a top priority.