Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (6 page)

Read Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All Online

Authors: Paul A. Offit M.D.

BOOK: Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All

13.59Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Like pertussis, diphtheria is caused by a bacterium:

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

. The bacterium causes a large, painful membrane to form on the back of the throat that can suffocate its victim; it also makes diphtheria toxin, which harms the brain, heart, and kidneys. (In the early 1900s, diphtheria was one of the biggest killers of young children.) Protection against diphtheria is afforded by immunity to this single toxin. So, when researchers wanted to make a diphtheria vaccine, all they had to do was grow toxin-producing bacteria in nutrient fluid, filter the bacteria out of the fluid, and leave the toxin behind. Then they inactivated the toxin with chemicals. Inactivated toxin is called toxoid.

Corynebacterium diphtheriae

. The bacterium causes a large, painful membrane to form on the back of the throat that can suffocate its victim; it also makes diphtheria toxin, which harms the brain, heart, and kidneys. (In the early 1900s, diphtheria was one of the biggest killers of young children.) Protection against diphtheria is afforded by immunity to this single toxin. So, when researchers wanted to make a diphtheria vaccine, all they had to do was grow toxin-producing bacteria in nutrient fluid, filter the bacteria out of the fluid, and leave the toxin behind. Then they inactivated the toxin with chemicals. Inactivated toxin is called toxoid.

Tetanus vaccine is made exactly the same way. Tetanus, or lockjaw, is caused by the bacterium

Clostridium tetani

. As with diphtheria, tetanus bacteria make just one harmful toxin—and protection against tetanus is afforded by immunity to that toxin. Accordingly, diphtheria and tetanus vaccines each contain only a single protein.

Clostridium tetani

. As with diphtheria, tetanus bacteria make just one harmful toxin—and protection against tetanus is afforded by immunity to that toxin. Accordingly, diphtheria and tetanus vaccines each contain only a single protein.

Making a pertussis vaccine, on the other hand, hasn’t been easy. That’s because the pertussis bacterium doesn’t make just one protein that causes disease. It makes many; at least nine pertussis proteins play an important role in infection. Some of these proteins are part of the structure of the bacteria; other proteins, like diphtheria and tetanus toxins, are secreted by bacteria. When Kendrick and Eldering were making their vaccine, they didn’t know how many pertussis proteins caused disease. So they took bacteria, grew them in nutrient fluid, and treated the whole concoction with carbolic acid. Their vaccine, made using whole, dead pertussis bacteria, contained more than three thousand pertussis proteins.

When Kathi Williams, Jeff Schwartz, and Barbara Loe Fisher organized Dissatisfied Parents Together, the process of making pertussis vaccine wasn’t much different from that used by Kendrick and Eldering forty years earlier. Because the vaccine was so crudely made, it had a higher rate of side effects than any other vaccine. To put this in perspective, in 1982, when Lea Thompson galvanized the public with

Vaccine Roulette

, in addition to the DTP vaccine, children received the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine and the oral polio vaccine. Measles vaccine contains ten viral proteins; mumps, nine; rubella, five; and polio, fifteen. This meant that the total number of immunological challenges in the measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, and tetanus vaccines combined was forty-one, about a hundredth the number contained in the pertussis vaccine alone.

Vaccine Roulette

, in addition to the DTP vaccine, children received the combination measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine and the oral polio vaccine. Measles vaccine contains ten viral proteins; mumps, nine; rubella, five; and polio, fifteen. This meant that the total number of immunological challenges in the measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, and tetanus vaccines combined was forty-one, about a hundredth the number contained in the pertussis vaccine alone.

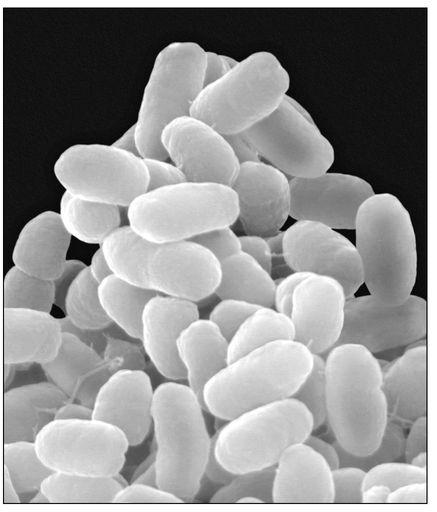

Pertussis vaccine was the only vaccine given to American children made from whole, dead bacteria. (Courtesy of Dennis Kunkel Microscopy/Corbis.)

By the early 1980s, only one study in the United States had carefully examined the side effects of pertussis vaccine. During her program, Lea Thompson introduced the researcher who did it: Dr. Larry Baraff of the UCLA Medical Center. Baraff explained why he had done the study: “Because the Food and Drug Administration was concerned that this sort of public panic might spread [from England] to the United States, they wanted to document that the vaccine was safe and not associated with severe consequences.”

Baraff’s findings were striking. Of every thousand children given pertussis vaccine, eighty suffered redness and swelling at the site of injection (more than an inch wide); about five hundred had pain; five hundred had fever; three had fever greater than 105 degrees; three hundred felt drowsy; five hundred were fretful; twenty didn’t want to eat; ten cried for more than three hours (and as long as twenty-one hours); and one had an unusual, high-pitched cry (Kathi Williams’s child suffered this side effect). Further, of every ten thousand children vaccinated, six suffered seizures with fever and six had decreased muscle tone and responsiveness that lasted for a few hours. (This side effect, called Hypotonic-Hyporesponsive Syndrome, can cause children to be pale and limp for hours—devastating for any parent to watch. Barbara Loe Fisher’s child most likely suffered this problem.) Baraff explained that these side effects were the result of the archaic technology used to make the vaccine. “I don’t think that this is the type of vaccine that would be produced today,” he said. “If this vaccine were produced in 1980, instead of in the 1930s and ‘40s, there would be a different type of technology available and we would make a more purified vaccine.” Baraff was right. Taking advantage of advances in protein chemistry and protein purification, by the mid-1990s, safer pertussis vaccines—containing only two to five pertussis proteins instead of three thousand—were licensed.

Although transient side effects following pertussis vaccine were common, that wasn’t at issue. The important question raised by

Vaccine Roulette

was whether the vaccine could cause permanent harm, such as epilepsy and mental retardation. Answering this question isn’t as easy as it seems. That’s because every year in the United States, in England, and throughout the world, children suffer epilepsy and mental retardation; this has been true for centuries, well before the pertussis vaccine was invented. Also, symptoms of epilepsy and retardation often occur in the first year of life, the same time that children are receiving three doses of vaccine. Given the widespread use of pertussis vaccine, most children destined to develop seizures or mental retardation anyway would likely have received it, some within the previous twenty-four or forty-eight hours. So, the only way to figure out whether the vaccine was the problem was to study thousands of children who did or didn’t get it. If the vaccine were responsible, the risk of epilepsy or retardation would be greater in the vaccinated group. At the time of

Vaccine Roulette

, only one large-scale study of children had been completed: David Miller’s. The next fifteen years, during which other investigators examined this question, were not kind to David Miller’s study.

Vaccine Roulette

was whether the vaccine could cause permanent harm, such as epilepsy and mental retardation. Answering this question isn’t as easy as it seems. That’s because every year in the United States, in England, and throughout the world, children suffer epilepsy and mental retardation; this has been true for centuries, well before the pertussis vaccine was invented. Also, symptoms of epilepsy and retardation often occur in the first year of life, the same time that children are receiving three doses of vaccine. Given the widespread use of pertussis vaccine, most children destined to develop seizures or mental retardation anyway would likely have received it, some within the previous twenty-four or forty-eight hours. So, the only way to figure out whether the vaccine was the problem was to study thousands of children who did or didn’t get it. If the vaccine were responsible, the risk of epilepsy or retardation would be greater in the vaccinated group. At the time of

Vaccine Roulette

, only one large-scale study of children had been completed: David Miller’s. The next fifteen years, during which other investigators examined this question, were not kind to David Miller’s study.

The first flaw with the notion that pertussis vaccine caused brain damage was that it didn’t make biological sense. Anyone working in a hospital knew that natural pertussis infection could cause brain damage because of decreased oxygen in the bloodstream caused by unrelenting coughing. But the pertussis vaccine—made of killed bacteria that didn’t grow in the lungs or windpipe—didn’t cause coughing.

So what could have caused brain damage? One prevalent theory was that the pertussis vaccine contained small amounts of endotoxin : part of the surface of a variety of bacteria (including pertussis) and a very potent poison. In 1978, a researcher named Mark Geier published a paper claiming that commercial preparations of pertussis vaccine contained small quantities of endotoxin. Because even a little endotoxin can have devastating effects, Geier reasoned that severe reactions to pertussis vaccine might be caused by endotoxin. The problem with this logic is that endotoxin causes brain damage by inducing a cascade of events that includes fever, rapid heart rate, chills, low blood pressure, shock, and decreased oxygen to the brain. Indeed, the one symptom that occurs in everyone experimentally inoculated with endotoxin is fever. But many children with seizures and retardation following pertussis vaccine never had fever. And pertussis vaccine didn’t cause low blood pressure or shock, another common response to endotoxin.

Epidemiological studies didn’t support Miller’s study, either.

In 1956, the Medical Research Council in England studied more than thirty thousand children for two years. It couldn’t find even one who had suffered brain damage as a result of the pertussis vaccine.

In 1962, Bo Hellström at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm studied eighty-four healthy infants who had received DTP and later suffered high fever or decreased responsiveness. Hellström performed electroencephalograms on children six and twenty-four hours after vaccination, reasoning that if the vaccine was affecting the brain, then the EEGs, which can detect even slight alterations in brain wave activity, should be abnormal. But they weren’t. All the children had perfectly normal EEGs.

In 1983, two years after David Miller’s study was published, T. M. Pollack and Jean Morris, researchers at the Public Health Laboratory and Department of Community Medicine in London, published their own study. They analyzed 134,700 children in the North West Thames Region of England who had received three doses of DTP and compared them to 133,500 children who had received DT alone. Their study enabled them to isolate the effect of the pertussis component of the vaccine. They, too, couldn’t find what David Miller had found.

Also in 1983, three neuropathologists in England studied the brains of twenty-nine children whose deaths had been blamed on pertussis vaccine. Some had died within a week of getting the vaccine; others had suffered epilepsy, mental retardation, or physical disabilities. The investigators were looking for anything that tied these cases together—some indication that the vaccine had caused the problem. But no distinct pathological finding linked the cases.

In 1988, researchers in Denmark took advantage of a natural experiment. Before April 1970 children in Denmark were vaccinated with the DTP vaccine at five, six, seven, and eighteen months of age. But after April 1970 they were given the pertussis vaccine at five and nine weeks and again at ten months of age. Investigators reasoned that if epilepsy were a consequence of receiving pertussis vaccine, then the onset of seizures should change with the changing schedule. But it didn’t.

Six years after the airing of

Vaccine Roulette

, a study was finally performed on American children. In 1988, researchers from the department of epidemiology at Harvard’s School of Public Health and the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound in Seattle examined the records of more than thirty-five thousand children. They wanted to determine whether epilepsy was more common in those recently vaccinated. It wasn’t.

Vaccine Roulette

, a study was finally performed on American children. In 1988, researchers from the department of epidemiology at Harvard’s School of Public Health and the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound in Seattle examined the records of more than thirty-five thousand children. They wanted to determine whether epilepsy was more common in those recently vaccinated. It wasn’t.

Two years later, Marie Griffin and colleagues from Vanderbilt University published a study of more than thirty-eight thousand children in Tennessee, looking for a relationship between DTP and brain damage. Again, they were unable to find what David Miller had found.

The number, reproducibility, and consistency of these studies prompted a response from public health agencies. In 1989, the British Pediatric Association and the Canadian National Advisory Committee on Immunization concluded that pertussis vaccine had not been proved to cause permanent harm.

In 1990, the same year Marie Griffin published her paper, Gerald Golden—Shainberg professor of pediatrics, director of the Boling Center for Developmental Disabilities, and professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee—reviewed the evidence. Golden was unequivocal in his conclusions. “A syndrome of pertussis vaccine encephalopathy was first reported fifty-six years ago,” he wrote, referring to the 1933 report of two deaths following pertussis vaccine in Copenhagen. “Analysis of the recent literature, however, does not support the existence of such a syndrome and suggests that

neurological events after immunization are chance temporal associations

.” James Cherry, the pediatric infectious diseases specialist from UCLA, seconded Golden’s conclusions regarding the vaccine-brain damage link, writing that it was “time to recognize it as the myth that it is.”

neurological events after immunization are chance temporal associations

.” James Cherry, the pediatric infectious diseases specialist from UCLA, seconded Golden’s conclusions regarding the vaccine-brain damage link, writing that it was “time to recognize it as the myth that it is.”

In 1991, the Institute of Medicine—an independent research institute within the U.S. National Academies of Science—concluded that the association between pertussis vaccine and brain damage remained unproved. An ad hoc committee for the Child Neurology Society agreed, stating, “Case reports have raised the question as to whether there is an association between pertussis vaccine and progressive or chronic neurological disorders, but controlled studies have failed to prove an association.”

More evidence mounted.

In 1994, researchers from the University of Washington and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention teamed up to do yet another study. They evaluated more than two hundred thousand children in Washington and Oregon and concluded: “This study did not find any statistically significant increased risk of onset of serious acute neurological illness in the seven days after DTP vaccine.”

On March 10, 1995, seizure disorder following DTP vaccine was removed from the Vaccine Injury Compensation Program’s list of compensable injuries because “no medical evidence” existed to support the presumption—ironic, given that the program was born of this specific concern.

Finally, in 2001, researchers working with a group of health-maintenance organizations performed the clearest, most definitive study to date. Using computerized records, investigators analyzed the occurrence of seizures in three hundred and forty thousand children given DTP compared with two hundred thousand children who received no vaccine. They concluded: “There are significantly elevated risks of febrile seizures after receipt of DTP vaccine, but these risks do not appear to be associated with any long-term, adverse consequences.” (Although frightening to witness, seizures caused by fever, which occur in as many as 5 percent of young children, don’t cause permanent harm.)

Other books

This Calder Range by Janet Dailey

A Christmas to Remember by Jenny Hale

Accent Hussy (It Had 2 B U) by V. Kelly

The Counterlife by Philip Roth

Bonnie by Iris Johansen

Whisper by Chris Struyk-Bonn

Acceptance (Club X Book 5) by K.M. Scott

Inherited Magic by Andrew Gordinier

In Want of a Wife? by Cathy Williams