Days of Rage (81 page)

Authors: Bryan Burrough

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century, #Political Science, #Political Ideologies, #Radicalism

Baraldini was convicted of charges related to the prison break. Her forty-three-year sentence drew protests from leftists in her native Italy. Under an agreement with the Italian government, she was transferred to a prison outside Rome in 1999, freed on work release in 2001, and paroled in 2006. Today she lives with her partner, a chef, in Rome, where she sat for a series of interviews in 2013.

Several of her peers have not been so fortunate. Mutulu Shakur was captured in Los Angeles in 1986. Convicted of his role in the Brink’s robbery, he drew a sixty-year sentence. He remains incarcerated today at a federal prison in Adelanto, California. Donald Weems, better known as Kuwasi Balagoon, died of AIDS in prison in 1986. After testifying against several of his comrades, Tyrone Rison is believed to have entered a witness protection program. Baraldini, for one, says his betrayal will never be forgotten. “Tyrone Rison, mark my words, he will be killed,” she says today. “You think some things are over. That will never be over. Tyrone Rison will never be over.”

Of the white activists who aided the Family, only Judy Clark and David Gilbert remain in New York prisons. Clark is at the Bedford Hills Correctional Facility for Women in Westchester County, where she trains guide dogs; she met with the author but declined to be interviewed on the record. Gilbert remains at the Auburn Correctional Facility in northern New York. An avid writer, he published a memoir in 2012. The other white women are now free. Susan Rosenberg received a fifty-eight-year sentence related to possession of explosives. She was granted clemency by President Clinton in 2001. Kathy Boudin was paroled from Bedford Hills in 2003. Today, after an appointment that drew criticism from the New York tabloids, she is an adjunct professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work.

After recovering from her self-inflicted gunshot wound following the

Brink’s robbery, Marilyn Buck initiated one final chapter in her struggle against the U.S. government. Together with five other longtime underground figures, including Susan Rosenberg and the onetime Weatherman Laura Whitehorn, she formed the “Armed Resistance Unit,” which took credit for eight bombings between 1983 and 1985, including a November 7, 1983, bombing of the U.S. Senate. That bomb, left under a bench, demolished a corridor, blowing off Senate Minority Leader Robert Byrd’s office door. Buck was arrested in Dobbs Ferry, New York, in May 1985; the others were all rounded up as well. All drew lengthy sentences. All those still alive have been freed.

Six members of Ray Levasseur’s United Freedom Front were convicted on conspiracy charges at a federal trial in Brooklyn in 1986. The highlight came when Levasseur, acting as his own attorney, cross-examined Edmund Narine, the would-be cabbie who lost his leg in the group’s first bombing, at the Suffolk County Courthouse in 1976. (The group was later put on trial in Massachusetts, on charges of seditious conspiracy; this time all were acquitted or had charges dropped, in 1989.) Richard Williams, who also drew a life sentence for the murder of Trooper Philip Lamonaco, died of complications from hepatitis in a federal prison hospital in 2005. Tom Manning and Jaan Laaman remain in federal facilities today. Carol Manning, friends say, works in a factory in Maine. Pat Gros, who left Levasseur in the 1990s, is now a grandmother and works as a paralegal in Brooklyn.

Levasseur himself drew a forty-five-year sentence. He served his time at the federal prison in Atlanta and at the Colorado “Supermax” prison. After twenty years, a full thirteen of which were spent in solitary confinement, he was paroled in 2004. Today he lives with his second wife in a farmhouse they built in a field outside Belfast, Maine. Active in efforts to free underground figures who remain in prison, he turns seventy in 2016.

A second contingent of FALN fighters launched a brief second series of bombings, mostly in New York, in the early 1980s. Surveillance of a number of FALN supporters in the Chicago area eventually led the FBI to Willie Morales. In early 1983 the Bureau alerted Mexican authorities that Morales was hiding in the city of Puebla, southeast of Mexico City. When police went to arrest him, however, they found that Morales had five bodyguards. A

shoot-out ensued. One policeman was killed, and all of the bodyguards. Morales was captured, but a U.S. extradition requests was denied, and he was eventually released and allowed to immigrate to Cuba, where he lives to this day.

Eighteen members of the FALN served lengthy prison sentences for their roles in the group’s two campaigns. In the mid-1990s a clemency campaign drew the support of former president Jimmy Carter and ten Nobel Laureates. In 1999, with his wife, Hillary, seeking the support of Hispanic voters for a senatorial campaign in New York, President Bill Clinton offered clemency to sixteen of those imprisoned; all but two accepted. Both the House and the Senate passed measures condemning Clinton’s action, which remains controversial in conservative circles to this day. Marie Haydee Torres, who (along with her husband) was not offered clemency, was released after serving almost thirty years, in 2009; today a friend says she lives in Miami. Carlos Torres was released from an Illinois prison in 2010. A crowd of five hundred supporters held a celebration in Chicago; an even larger crowd welcomed him on his return to Puerto Rico. Oscar López remains in a federal prison in Terre Haute, Indiana. He comes up for parole every few years. His supporters—and there are many in the Puerto Rican and radical communities—campaign for his release. In 2014 the Puerto Rican Day Parade in New York honored him as a “Puerto Rican patriot” who “was not convicted of a violent crime.”

Of all those who went underground during the 1970s, few have gone on to more productive lives than alumni of the Weather Underground. Other than those who became involved with Mutulu Shakur, only Cathy Wilkerson served prison time, all of eleven months, on explosives charges related to the Townhouse. Most resumed more or less normal lives. Wilkerson remains a math instructor in the New York schools; she lives in Brooklyn with her longtime partner, the radical attorney Susan Tipograph. Ron Fliegelman worked as a special-education teacher in the New York schools for twenty-five years, retiring in 2007; today he and his wife live in Park Slope, Brooklyn, and are raising a son. Mark Rudd is a retired community college teacher in Albuquerque and gives talks about the sixties. Howard Machtinger lives in Durham, North Carolina, where he has worked as a high school teacher and at the University of North Carolina; he remains active in education reform efforts.

Jonathan Lerner is a writer in New York. Russell Neufeld practices law in Manhattan. Robbie Roth taught social studies at Mission High School in San Francisco. Clayton Van Lydegraf died in 1992. Annie Stein died in 1981. Mona Mellis died in 1993.

Several Weather alumni have risen to respected positions in their professions with very few knowing what they did in the 1970s. After attending law school, Paul Bradley, the pseudonym for one of Dohrn’s right-hand men, went on to a twenty-five-year career at one of the nation’s most prominent law firms. Today he lives in the Bay Area, where he advises a small start-up company or two; no one outside his family and other alumni has any clue that he spent years placing bombs in San Francisco–area buildings. Leonard Handelsman, a Weatherman in the Cleveland collective, went on to a distinguished career in psychiatry, becoming a full professor at Duke University, where he was medical director of the Duke Addictions Program. According to his longtime friend Howard Machtinger, who gave a eulogy when Handelsman died in 2005, no one outside his family knew of his life in the underground. Obituaries celebrated him only as a noted psychiatrist. Another Weatherman mentioned in this book became an accountant at a Big Four accounting firm in Vancouver. Today he is retired and active in local charities; he is not named here because of legal concerns. Another alumnus heads a children’s charity in Ohio, where an Internet biography indicates he has been appointed by three governors to sit on state task forces.

Bernardine Dohrn has been a clinical associate professor of law at Northwestern University for more than twenty years. She has been active in efforts to reform the Chicago public schools and in international human rights activities. She has never disavowed her years as a Weatherman. Jeff Jones and Eleanor Stein were finally arrested in Yonkers, New York, in 1981 after the FBI received a tip on their whereabouts during the Brink’s investigations. Jones received probation on old explosives charges and became an environmental writer and activist in upstate New York, where he and Stein live today. Stein received a law degree from Queens College in 1986 and is today an administrative law judge with the New York State Public Service Commission. Michael Kennedy, who represented certain of Weather’s leaders, is today one of the most prominent attorneys in New York. Kennedy, who has served

as a special adviser to the president of the United Nations General Assembly, lives with his wife, Eleanore, in a sumptuous apartment overlooking Central Park. Thanks to one of his old marijuana clients, he also happens to own

High Times

magazine.

All these people, from Mark Rudd to Bernardine Dohrn, had been living upright lives for more than twenty years when the final underground fugitives, those of the SLA, were arrested. The most celebrated of these cases was that of Kathy Soliah, who had avoided capture for almost twenty-five years when, in 1999, she was twice profiled on the television show

America’s Most Wanted

. Following a viewer’s tip, the FBI arrested her in St. Paul, Minnesota, where she was living as Sara Jane Olson; she had married a doctor, briefly lived in Zimbabwe, and given birth to three children. Taken back to California in handcuffs, Soliah initially pled guilty to a pair of old explosives charges, then withdrew her plea, after which she was sentenced to two consecutive ten-years-to-life terms.

The case generated a flurry of new interest in the SLA’s murder of Myrna Opsahl at the Crocker National Bank robbery in 1975, which had never been prosecuted. In 2002 charges of first-degree murder were filed against Soliah, as well as Michael Bortin and Bill and Emily Harris, all of whom had been living quietly since brief jail sentences in the 1970s. Later that year police in South Africa arrested the last of the SLA fugitives, Jim Kilgore, who had been working under an assumed name as a history professor, married an American woman, and fathered two children. All five ended up pleading guilty; Emily Harris, now Emily Montague, admitted she had fired the fatal shot but insisted that the gun had gone off accidentally. The heaviest of the sentences was hers, eight years. By May 2009, when Kilgore was released, all had served their time. Today, of all those who joined the SLA, only Joseph Remiro remains behind bars, for the murder of Marcus Foster in 1973.

After her pardon and release from prison in 1979, Patty Hearst, now known as Patricia Campbell Hearst Shaw, married one of her bodyguards, Bernard Shaw, and settled down to a quiet life as a socialite and heiress. Today she is perhaps best known for occasional acting jobs, most notably in a series of cameos and small roles in movies by the independent filmmaker John Waters. Her husband, with whom she raised two children, died in 2013.

Hearst, like many of those who lived underground all those years ago, rarely speaks of her experiences today. Few do. Many have moved on; others will talk openly only with fellow radicals. When I put the question of legacy to Sekou Odinga, he heaved a heavy sigh and crossed his hands in his lap. He was sixty-eight the day we spoke. “Will I be remembered?” he asked. “I don’t really care. Let’s be real. What I care about are my children, and your children, and the children of tomorrow. I want them to study the past, and learn about it and carry on. Because America has only gotten worse. It has. At some point it’s gonna fall, because all empires fall. It’s on its way right now. There’s not going to be any America in fifty years. There’s not. And the youth of today has to be ready to pick up the pieces when that happens.”

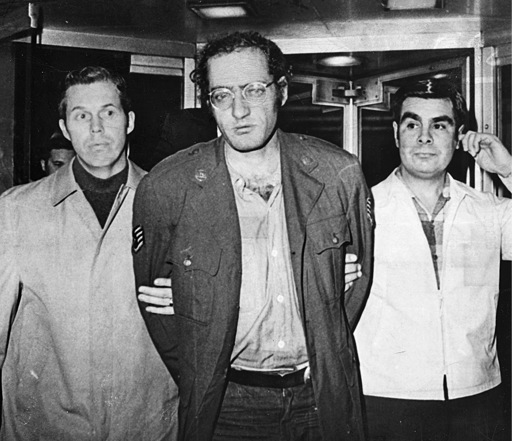

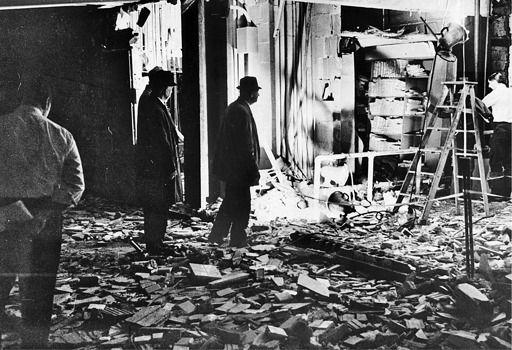

Sam Melville

, and

Jane Alpert

, led the first significant radical bombing group, which detonated nearly a dozen bombs around Manhattan in the second half of 1969. Above, detectives nose through the wreckage of a Commerce Department office the group bombed in Foley Square that September.