Dare to Be a Daniel (4 page)

Read Dare to Be a Daniel Online

Authors: Tony Benn

His real love was London and he had a desire to improve the lot of the Londoner. He was a member of the first London County Council, which met in 1889 with a massive 2:1 Progressive majority against the Moderates (Conservatives).

Writing of that occasion, John Benn said, ‘The Progressives were already full of great schemes, mostly framed to secure a millennium for London by return of post. The Reformers, fresh from the polls, hotly resented any obstruction to their wishes. They were indeed in deadly earnest.’ John was a genuine entrepreneur, combining enterprise with a passionate belief in municipal trading, including the common management and ownership of the tramways, gas, water and electricity. The story of the introduction of electric trams, and Grandfather’s role, is most interesting.

The Progressives’ strategy was to buy out the many privately owned horse-drawn tram companies, whose operations brought chaos to London’s transport system, and to introduce electric trams. Despite stubborn resistance, the first LCC electric trams were inaugurated in May 1903 and ran until 1952. John Benn believed that the revenue from fares could be used to reduce rates and alleviate the ‘disgraceful conditions’ of the poor; tramway employees received a minimum wage (twenty-five shillings) for a maximum sixty-hour week.

My grandfather fought a notable battle against the ‘surface’ or ‘stud’ system for trams, whereby connection was made between the tram and a wire contact in the road. The system was introduced by the Moderates and was supposedly cheaper, but had caused the death of a horse and cars to catch fire, because many of the studs were found to be live. John spoke about ‘the terrible story of the Mile End Road from June 24th to July 12th last. Fifty live studs a day injured people, roasted horses, caused fireworks

at

night and the danger of a fatal accident to any person who chanced to touch a live stud.’ The tram company sued my grandfather for libel, and in November 1910 the court assessed damages against him at £12,000. The judge directed that ‘£5,000 must be secured within 14 days’. An order was put on his property to guarantee payment and, anticipating the bailiffs, my grandmother marked some of the furniture as hers; but my grandfather won on appeal in March 1911. He was congratulated by, among others, a man called Key who wrote, ‘I felt as if all the bells ought to be ringing and the flags in the City waving.’

John Benn also advocated leasehold franchisement, the taxation of land values, the abolition of all school fees and public ownership of the Port of London. And he was a strong supporter of women’s rights, vigorously defending Lady Sandhurst and two other women who had been chosen by the council as aldermen, but who were disqualified by the courts, because they were women.

John’s greatest passion was to secure for Londoners the right to have their own elected government to replace the hotchpotch of boards and vestries, which were as corrupt as they were inefficient. He believed that London, as the greatest city in the world, should be allowed to take over responsibility for the new and sprawling community growing up outside the old City of London, and the City itself under its Lord Mayor and aldermen and livery companies. These enjoyed immense wealth, but had no interest in the people who poured into the City every day to work in the offices and warehouses from which its wealth was derived – and John always believed that its riches should be shared.

As Chairman of the Housing Committee, he was very proud of what the new LCC was able to achieve, acquiring great tracts of land for building. And he campaigned actively to raise the rates

of

relief in 1893–4 at a time when distress among the poor was at its worst for twenty years.

In 1892 my grandfather had supported John Burns in his campaign for trade-union rates of pay, hours and conditions for contractors to the council. That same year, when the National Telephone Company asked permission to have the streets of London dug up to accommodate its new cable system, the LCC objected, and John led the delegation to see the Postmaster-General to demand that the new telephone service should be seen as a public utility and brought into public ownership.

Arnold Morley, the Postmaster General, refused, saying that the telephone was a luxury. To this my grandfather, showing great foresight, replied that ‘The day will come when ordinary people will be able to order their groceries through the telephone.’ He lived to see a Liberal government bring the National Telephone Company into the Post Office’s own system.

He was equally radical in his attitude to the police, on one occasion calling for an inquiry into the severe injuries sustained, at the hands of the police, by unemployed demonstrators at Tower Hill. And he moved the motion in the council in April 1889 which declared it to be necessary and expedient that the LCC should, in common with all other municipal bodies, have control of its own police. However, London never succeeded in this because Sir William Harcourt, the Home Secretary, argued that the dangers of ‘Irish terrorism’ necessitated government control.

In 1894 Lord Salisbury denounced the LCC as the place where ‘collectivist and socialistic experiments were tried’; the

Daily Mail

included John Benn, along with John Burns and Sidney Webb, on its ‘blacklist’ in the LCC elections that year.

In 1892 my grandfather had been elected MP for St George’s-in-the-East,

declaring

that he aspired ‘to the honour of being a member for the backstreets’. He used this little verse as his slogan:

Friends of Labour, Working Men

Stick to Gladstone, Vote for Benn.

John was a passionate believer in Home Rule for Ireland and defeated C. J. Ritchie, who was then President of the Local Government Board, receiving a message of congratulations from Mr Gladstone himself.

After losing his seat in 1895 by eleven votes, having forgotten to vote for himself, he stood in the Deptford by-election in 1897, calling for a bigger house-building programme and for cheap fares for workmen. A scurrilous campaign was mounted against him in a newspaper called

The Sun

owned by Harry Marks, which circulated to every elector a special edition attacking John Benn. He was defeated by 324 votes, a result that led John Burns to announce that ‘The election had been won by a newspaper owned by blackguards, edited by scoundrels.’ Later, in the General Election of 1900, my grandfather stood for Bermondsey, where he was again defeated. He was ultimately successful in re-entering Parliament for Devonport.

As Chairman also of the LCC, he set out in 1904 his political philosophy in these words, describing the role of the council as guardian of the plain citizen, and foreshadowing the Beveridge Report forty years later:

The Council now follows and guards him from the cradle to the grave. It looks after his health, personal safety and afflicted relatives; it protects him from all sorts of public nuisances; it

endeavours

to see that he is decently housed or itself houses him.

It keeps an eye on his coal cellar and his larder; it endeavours to make his city more beautiful or convenient; it looks after his municipal purse and corporate property and treasures his historical memories.

It tends and enriches his broad acres and small open spaces and cheers him with music.

It sees that those it employs directly or indirectly enjoy tolerable wages and fair conditions.

It speaks up for him in Parliament, both as to what he wants and what he does not want; and last and greatest of all, it now looks after his children, good and bad, hoping, if it is possible, to make them better and wiser than their progenitors.

In 1910 he spoke alongside Keir Hardie at a rally in Hyde Park in support of Lloyd George’s Budget.

One of the last decisions taken by the LCC was to acquire the site on the river on which its home, County Hall, was built. It was Mrs Thatcher who abolished its successor, the Greater London Council, because she did not believe in any of the principles that John Benn espoused.

John was very popular with children and once composed a children’s prayer: ‘O God, please make the bad people good and the good people nice.’ He also wrote ‘The Christmas Pudding Song’ which I remember my father singing at Christmas, to the tune of ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’:

Once there was a pudding

At least I fancied so

She had three little children

Whose names I think you know

There was Peter Mincepie first

Michael Orange sitting by

And little Lucy Lemon who

Seemed just about to cry.

Chorus:

Sing a song of Pudding full of spice and plums

Crowned with glistening holly, when old Xmas comes

Pass the pudding plates and have another slice

And clap clap clap for Christmas time and everything that’s nice.

Worthy Mistress Pudding who had so wise a head

She always gave a raisin for everything she said

She plummed her neighbours up with spicy compliments

Her words were also eatable and with the currant went.

Chorus

Little Peter Mincepie was so cut up one day

He always was so crusty and had a nasty way

Of making very ill the folks who took him in

They couldn’t sleep a wink at night he kicked up such a din.

Chorus

Little Michael Orange was such a charming boy

To make his playmates happy was ever Michael’s joy

He covered them with juice and though they sucked him dry

This very happy little chap was never known to cry.

Chorus

Little Lucy Lemon whenever she was squeezed

She always pulled a nasty face and said ‘I won’t be teased’

She always was so cross she never got a kiss

Whatever you do, dear boys and girls, don’t get a face like this.

John Benn died in 1922, three years before I was born, and I am very sad never to have met him. As I have got older, I have come to appreciate what a tremendously progressive force local government has been in the history of our democracy. Had the Labour Party existed when he was first elected, he would certainly have been a member of it. He was a passionate advocate of what came to be known as ‘gas-and-water socialism’, which laid the foundations of the welfare state. After his death his son, my Uncle Ernest, opened the John Benn Hostel for homeless boys in the East End in memory of his father.

In 1958, when my dad was just over eighty, he did a broadcast for the BBC and his opening words were, ‘The chief interest of my family for four generations has been Parliament.’ He described how his grandfather, the Revd Julius Benn, had nominated James Bryce as the Liberal candidate for Tower Hamlets; how his father John had been elected for the same constituency in 1892, and he himself for Tower Hamlets in 1906. His broadcast ended by describing how my two eldest sons had sat in the gallery of the House of Lords waving to him, knowing that their father, their grandfather and both their great-grandfathers had been Members of Parliament. And he ended, ‘You will understand then what I mean when I speak of a parliamentary community and why I live so happy in a blaze of autumn sunshine.’

My dad could not know then that one of those little boys (my son Hilary) would himself become an MP for Leeds and is now a Cabinet minister, helping to make a record of five members of the family over four generations in Parliament in three centuries.

M

OTHER’S SIDE

On my mother’s side my Scottish ancestors were radical in nature, and it is said that my great-great-grandmother was in Stirling on the day of the execution of two Scots radicals – John Baird and Andrew Hardie – for armed insurrection in 1820.

My great-grandfather on Mother’s side was Peter Eadie, a Scots engineer who was apprenticed on the Clyde. The Eadies were farmers in Perthshire, but Peter travelled widely in Europe, as many Scottish engineers did in the nineteenth century, and was involved in building the railway station at Kilmarnock.

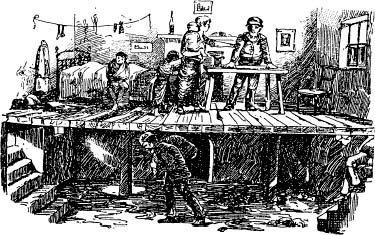

Peter Eadie was a very imaginative man. He invented a device called a Ring Traveller, which was a modest invention that was essential for the textile industry. And in his little house in Galashiels he designed and manufactured these tiny components, set up a small company and then moved to Paisley, a textile centre. There he built up a very successful business with two brothers (the company being called Eadie Bros and Co.) with £120 capital.

Politically he was a radical on Paisley council and disliked the ‘idle rich’ intensely. My mother said that the first time she heard the word ‘socialist’ was after the election of the Liberal government in 1906, when Peter declared that he might go further than them and ‘become a socialist’. In his capacity as a

Paisley

councillor, he supported votes for women and in 1913 wrote:

I will give my blessing to anyone who will bring in a measure to redress her [woman’s] wrongs. Of course I do not know all the circumlocutions of the House of Commons nor how long it would take them to do it, but if they would hand it over to the Paisley Town Council they would do the job at a sitting.