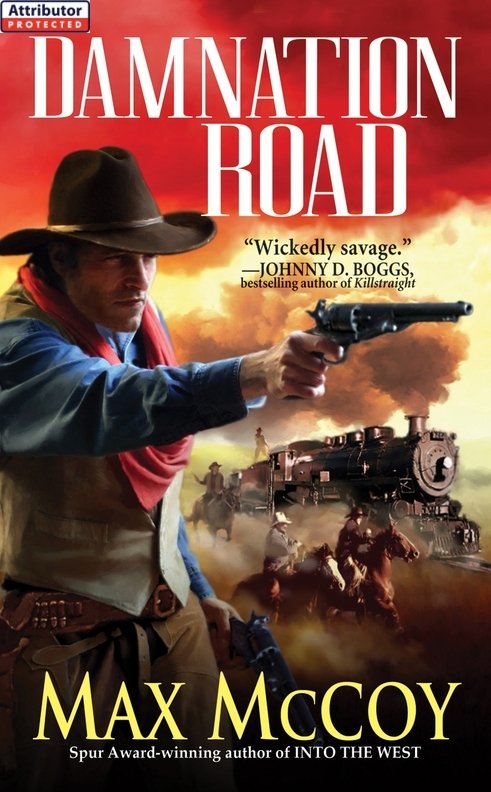

Damnation Road

Authors: Max Mccoy

Tags: #General, #Fiction, #Apache Indians, #Western Stories, #Westerns, #Treasure Troves, #Large Type Books, #Cultural Heritage

D

AMNATION

R

OAD

AMNATION

R

OAD

M

AX

M

C

C

OY

AX

M

C

C

OY

PINNACLE BOOKS

Kensington Publishing Corp.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

Kensington Publishing Corp.

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

For Karl Gregory

But you know yourself an outlaw, stubborn, vengeful, just, Bill Doolin cornered, a Dalton cut to pieces, a Younger hell-bent for home.

Â

âKim Horner, “Regression”

1898

O

NE

NE

Jacob Gamble limped into Farquharson and Morris Hardware, favoring his right leg, glancing behind him at dust-blown Oklahoma Avenue. His right boot was filled with blood and the red stuff oozed from the seams with every other step, leaving a sinuous trail on the freshly polished oak floor.

“Show you something?”

The clerk was a boy of seventeen and until a few moments before had been enthralled by a ruddy account in the

Police Gazette

of a Chicago meatpacker who had tired of his wife and disposed of her body in one of the sausage vats. The cover of the

Gazette

was a full-page illustration of three swarthy Spanish agents searching a disrobed and comely young American woman in her berth on a steamer in Havana Harbor.

Police Gazette

of a Chicago meatpacker who had tired of his wife and disposed of her body in one of the sausage vats. The cover of the

Gazette

was a full-page illustration of three swarthy Spanish agents searching a disrobed and comely young American woman in her berth on a steamer in Havana Harbor.

“Cartridges.”

Gamble slapped a revolver on the top of the display case so hard the boy was afraid the glass would crack. It was an old gun with a brass frame, an open top, and an octagonal barrel. It was filthy with residue and the rotten egg stench of recently discharged black powder radiated from the gun.

The boy whistled as he tossed the

Gazette

aside.

Gazette

aside.

“Navy Colt.”

The gun wasn't a Colt, it was an old cap-and-ball Manhattan converted to .38-caliber rimfire cartridges, and the boy hadn't even noticed that the loading gate and ejector rod had been placed opposite normal, making it a

left-handed

gun, but Gamble didn't have the will to correct him. Gamble was light-headed, there were splotches of white crowding his vision, and his legs were weak. He gripped the display case with his dirty hands to keep himself upright.

left-handed

gun, but Gamble didn't have the will to correct him. Gamble was light-headed, there were splotches of white crowding his vision, and his legs were weak. He gripped the display case with his dirty hands to keep himself upright.

“Carry this at Gettysburg, Granddad?” the boy asked as he picked up the Manhattan. “Damn, it's warm. You been target practicing?”

Gamble clenched his jaw and concentrated on forcing the whiteness back.

“You all right, mister? You look a might peaked.”

“Cartridges,” Gamble managed. “Thirty-eight rimfire.”

“Don't got 'em,” the boy said, rummaging among the boxes of ammo on the shelf behind the counter. “Had a box or two, a few months ago, maybe longer. Sold 'em. Have a couple of boxes of .38 Colt center fireâthat's what most conversions use nowadays. Got plenty of 38-40 Winchester. Everybody wants to shoot the same round in their rifles as their pistols.”

“I'm not everybody,” Gamble said. He took a couple of deep breaths and concentrated on forcing the whiteness back to the edges of his vision. “Show me something new.”

“Absolutely,” the boy said. “Probably time you replaced that ancient iron with something modern, if you ask me. Forty-five is the most popular caliber.”

Leaning over the display case, Gamble caught the ghost of his reflection: a jaw bristling with salt-and-pepper whiskers, a shock of long hair turning gray at the temples, a black leather patch over his right eye. His black coat was powdered with road dust and smeared at the elbows and cuffs with red clay.

“For my money, the best handgun is the .44 Russian,” the boy continued. “Top break, fast loading. Accuracy and power combined. A real manstopper.”

“What do you know about stopping a man, son?” Gamble took a deep breath, then exhaled slowly. “The Russian is what Bob Ford used to shoot Jesse James in the back of the head while Jesse stood on a chair dusting a picture. I'm predisposed against it.”

Gamble glanced over the row of Peacemakers, a couple of Bisleys, a variety of Smith & Wessonsâincluding a Russianâa half a dozen other brand names, many trash guns, and a vest pocket pistol of uncertain manufacture. Damn, he needed something. . .

bigger

. He glanced up at the rack of long guns, mostly lever-action rifles and shotgun doubles, Winchesters and Marlins and Stevens.

bigger

. He glanced up at the rack of long guns, mostly lever-action rifles and shotgun doubles, Winchesters and Marlins and Stevens.

“Hand me that Winchester.”

Gamble turned to glance through the front window to the street, and when he turned back the boy was holding out a heavy shotgun with a single barrel. Gamble was about to say he meant the lever-action carbine instead, but the big shotgun reminded him of a shoulder-mounted canon.

“Model 97,” the boy said. “Twelve gauge. Only been for sale a few months. Improvement over the slide gun of a few years back. Smokeless. Shoots the new Nitro shells.”

The gun was heavy. The boy said it was eight pounds and some change. Gamble put his right hand on the ribbed forestock and studied the tubular magazine slung beneath the barrel.

“Where's the lever?”

“You ain't seen one of these before, have you?” the boy asked smugly. “There's no lever. It's a slide action. You just pump it back and then forward again, and it puts a new shell in the chamber and you're still on target. Be careful, though, because if you hold down the trigger when you drive a shell home, it's going to fire.”

“Dandy.”

“You can stuff five rounds in the magazine, through the slot beneath the receiver, and keep one in the chamber. So, she's good for six shots, as fast as you can work that pump.”

Gamble found the release and pulled back the pump, which set the action into motion. The slide shot backward out of the top of the receiver, cocking the exposed hammer and grazing the top of his thumb. Then he drove the pump home, and the bolt. Together, the actions produced a metallic

ch-chink

! that presaged mayhem.

ch-chink

! that presaged mayhem.

“Helluva sound,” Gamble said.

“Imagine hearing that in a dark alley. I'd fill my pants.”

“I'm sure you would.” Gamble was sighting down the barrel, lining up the grooves on the top of the receiver that served as the rear sight with the bead at the far end of the thirty-inch barrel.

“What d'ya think?”

“It will do.”

“Knew you had a good eye.” If the boy realized he'd made a bad joke, he didn't show it.

“A box of shells.”

“What size shot?”

“Double buck.”

The clerk took a carton of Robin Hood Smokeless Powder Company shotgun shells from a shelf behind him and slid them across the top of the display case.

“What else?”

“Ammonia.”

While the boy went to retrieve the bottle from the shelf of cleaning supplies, Gamble ripped the top from one of the boxes. The shells weren't all brass, like Gamble was used to seeing, but had only a half-inch ring of brass at the base, with the rest being paper that was slick with wax.

“I'll be damned,” Gamble said.

“Can't shoot the Nitros in the old guns,” the boy said, placing the bottle on the top of the display case. “They're so hot they'll blow the bolt right back in your face. That's why they make 'em red, I guess.”

Gamble shoved the shell into the bottom of the shotgun's receiver.

“You'll have to wait to do that,” the boy said, and all the while Gamble was stuffing more shells into the gun. “There's a law about carrying loaded guns in the city limits. Just wait and I'll write up your ticket and we'll settle up.”

Gamble worked the pump, producing that bone-chilling sound again, then pushed one last shell into the bottom of the receiver.

“You want to live?”

The boy nodded.

“Then we

are

settled up.”

are

settled up.”

Gamble cradled the shotgun in the crook of his right arm and used his left hand to scoop up more of the bright red shells and shove them into the pockets of his dusty black coat.

“Jesus, mister,” the clerk said.

“Jesus has nothing to do with it,” Gamble said.

The whiteness came in on him hard just then, and he closed his eyes. His legs were numb and he felt himself sinking toward the floor. Then he heard shouting outside, and he pulled himself upright, and roughly uncorked the brown bottle. He pulled the bandanna from his neck, sprinkled some ammonia over it, then brought it toward his nose. The fumes seared his nostrils and brought the world back, fast and hard.

“You'd better get down, because it's going to be raining lead in about thirty seconds,” Gamble said.

“You the law?”

“Not by a damned sight.”

“Then you're ...”

“An outlaw.”

“A wicked man,” the boy said, grinning.

Some would say that, Gamble thought.

“How many men have you killed?”

Other books

The Winter Mantle by Elizabeth Chadwick

Real Men Don't Quit by Coleen Kwan

Master: An Erotic Novel of the Count of Monte Cristo by Colette Gale

B0089ZO7UC EBOK by Strider, Jez

The Chevalier (Châteaux and Shadows) by Philippa Lodge

A Cornish Christmas by Lily Graham

Hymn by Graham Masterton

One Long Thread by Belinda Jeffrey

The Croning by Laird Barron

The Silver Rose by Jane Feather