Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (27 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

The Bektaşis absorbed certain pre-Islamic and

Christian practices and rituals, which explains their acceptance, popularity,

and success among many urban and rural communities of the Balkans, particularly

in Albania. Using Holy Communion as a model, they served wine, bread, and

cheese when new members joined the order. The members of the order also

confessed to their sins and sought absolution from their

murşid

(spiritual

guide). In sharp contrast to Muslims who prescribed strict separation between

the two sexes, Bektaşi women participated in the order’s rituals without

covering their faces. A small group within the order swore to celibacy and wore

earrings as a distinctive mark. Under Ottoman rule, Bektaşi leaders

introduced the teachings of their order to various regions of the Balkans,

Anatolia, and the Arab Middle East, including Egypt. As the convents of the

order spread throughout the Balkan region, many Christians in Albania, Kosovo,

and Macedonia converted to Islam through Bektaşi teachings and activities.

Evliya Çelebi wrote that the Muslims of Gjirokaster in southern Albania were so

devoted to the first Shia imam, Ali, that, when sitting down or standing up,

they uttered “

Ya Ali

” (“Oh Ali”). According to Evliya Çelebi, these

Albanians studied and read Persian and, in sharp contrast to Muslims who

shunned alcohol consumption and public demonstrations of physical intimacy with

the opposite sex, they “were very fond of pleasure and carousing” as well as “shamelessly”

drinking wine and other intoxicating beverages. The Bektaşis also

celebrated weddings and the two Muslim feasts of

bayrams,

as well as

Persian Zoroastrian and various Christian festivals, such as

Nevruz

(Persian

New Year) and the days of St. George, St. Nicholas, and St. Demetrius, by

dancing and drinking, a behavior that was denounced by the devout traveler and

writer as “shameless” and “characteristic of the infidels.”

In his

Book of Travels,

Çelebi left his readers with

a vivid description of a “love intoxicated” Bektaşi

derviş

:

Meanwhile I took a close look at this dervish. He was

barefooted and bareheaded and raggedy. But his face and his eyes gleamed with

light, and his speech sparkled with pearls of wit. He was extremely eloquent

and quick witted. On his head perched a “water pot” headgear, with the turban

awry and adorned with twelve ruby-colored brands, like appliqué roses, standing

for the twelve leaders of the

Bektaşi

order, and signifying his

love for the dynasty (of Ali) and his devotion to the twelve

imams.

. .

. On his shirtless and guileless pure and saintly chest were marks of

flagellation he had received in Tabriz [a city in northwestern Iran] during the

Aşura ceremonies marking the martyrdom of el-Huseyn. . .

He

removed the “water pot” from his head revealing, just above his forehead, a “brand

of submission” the size of a piaster [a coin]. His purpose in displaying it to

us was to demonstrate that he was an adept in the holy law (

şeriat)

,

in the mystic path (

tarikat)

, in the mystic truth (

hakikat)

, and

in Gnostic wisdom (

marifet)

, and that he had submitted to the way of

Truth (

tarik-i hak

). On both arms were wounds and gashes of the four

companions of the Prophet, and on his left arm were brands and lashes of the

plain of Kerbela. He was mad, pure, wild, and radiant, but not exactly naked.

He was shaven in the saintly “four strokes” manner to indicate that he was free

of all forbidden things—thus there was no trace of hair, whether on his head,

mustache, beard, brow, or eyelashes. But his face was shining. In short, the

apron round his waist, the staff in his hand, the words “Oh Beloved of hearts”

on his tongue, the sling of David in his waistband, the

palheng

-stone (“a

carved stone the size of a hand with twelve flutings worn at the waist”) of

Moses, pomp of Ali, the decorative plumes, bells, and other ornaments [all

these indicated that he was] a companion of the foot-travelers, they were the

outfittings and instruments of poverty of the noble dervishes, and he himself

was the perfect mystic.

MEVLEVIS

The greatest rival of the Bektaşis was the Mevlevi

order, which enjoyed immense popularity among the members of the Ottoman ruling

elite. The founder of the order, and one of the most beloved Persian poets, was

Mevlana Celaledin Rumi (Persian: Mowlana Jalaludin Mohammad Balkhi, also known

as Mowlavi), born in 1207 in Balkh in today’s northern Afghanistan. His father,

Bahauddin Walad, a renowned scholar, theologian, and mystic, fled his home

before the arrival of the Mongols in 1215 and took his family to Konya, the

capital of the Rum Seljuk state in central Anatolia. Rumi lived, wrote, and

taught in Konya until his death in 1273. His body was buried beside his father

under a green tomb, which was constructed soon after his death. The mausoleum

has served as a shrine for pilgrims from the four corners of the Islamic world,

as well as those of other faiths who revere his teachings and mystical poetry.

Rumi would have been an ordinary mystic and poet had it not

been for an accidental encounter in 1244 with the wandering Persian Sufi master

Shams-i Tabrizi, who hailed from Tabriz, a city in northwestern Iran. Shams

inspired Rumi to compose one of the masterpieces of Persian poetry,

Divan-i

Shams-i Tabrizi

(The Divan of Shams of Tabriz), in which Rumi expresses his

deep love, admiration, and devotion for Shams, who had transformed his life.

This was followed by the

Masnavi

(Turkish:

Mesnevi)

, a

multivolume book of poetical genius and fantastic tales, fables, and personal

reflections that Rumi completed after the disappearance of Shams. Rumi’s poetry

transcends national, ethnic, and even religious boundaries, and focuses

primarily on the spiritual journey to seek union with God. Love for fellow

human beings is presented in his poems as the essence of the mystical journey.

The mystical order that was established during Rumi’s

lifetime (which came to be known as Mevleviyya) was distinguished from other

Sufi orders by the significance it gave to

sema,

a music and

whirling/dancing ritual performed in a circular hall called

sema hane.

Imitating

their master’s love for the musical ceremony that inspired singing and dancing,

Mevlana’s followers employed spinning and whirling to reach a trance-like

state. While the majority of Muslims shunned singing and dancing, the Mevlevi

dervişes

made music and dancing the hallmark and central tenet of their order.

Because of its popularity, power, and influence, the

Mevlevi order was subjected to frequent attacks and persecution from the ulema,

who denounced their use of music and dancing as un-Islamic. Thus, in 1516, when

Selim I was moving against the Safavid dynasty in Iran, the

şeyhülislam

persuaded the sultan to order the destruction of Rumi’s mausoleum in Konya,

which served as the physical heart of the order. Fortunately for the Mevlevis,

the order was repealed and the mausoleum and center were spared.

Despite numerous campaigns of harassment by the members of

the religious establishment, Ottoman sultans and government officials continued

to show their respect and reverence for the Mevlavi order by showering its

leaders with gifts and favors. For example, in 1634, Murad IV assigned the poll

tax paid by non-Muslims of Konya to the head of the Mevlevi order. In 1648, the

chief of the Mevlevi order “officiated, for the first time, at the ceremony of

the girding on of the sword of Osman, which marked the accession of a new

sultan,” a privilege that remained with the order until the end of the Ottoman

dynasty. The close relationship between Ottoman sultans and the leaders of the

Mevlevi order continued into the 19th century. The reform-minded Selim III (1789–1807)

visited the Mevlevi

tekkes

so frequently that the musical ceremony,

which had been performed only on Tuesdays and Fridays, was performed daily in a

different

tekke

on each day of the week. Outside Istanbul, however, the

ceremony continued to be performed only on Fridays. This visible support

allowed the order not only to survive against attacks from the ulema but also

grow and expand into the four corners of the Ottoman Empire.

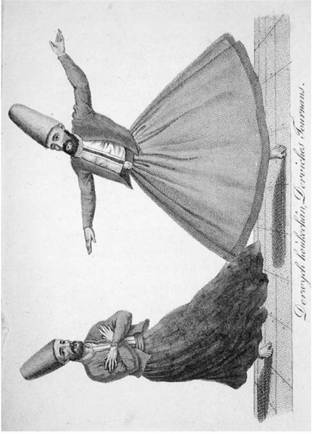

Dancing dervishes. Anonymous, c.

1810.

NAK

Ş

BANDIS

A latecomer among the Sufi orders in Istanbul was the

Nakşbandiyya

(Naqshbandiyya)

Sufi order, which arrived in the Ottoman Empire from

Central Asia in the late 15th century. The order traced its origins to the

Persian mystic and teacher Khawjah Bahauddin Naqshband (d.1389), who lived and

taught in Central Asia in the 14th century. The order immediately attracted a

large following because, more than any other mystical brotherhood, its

teachings and practices corresponded with the established rules and practices

of Sunni Islam. Greatly influenced by the writings of the Persian theologian, mystic,

philosopher, and jurist Ghazali (1058–1111), the Nakşbandis believed that

mysticism could not negate anything that was taught by the Quran and the

examples, deeds, sayings, and customary practices (

sunnah)

of the

prophet Muhammad. The members of the order closely observed the daily prayers,

fasts, and other observances prescribed by the Islamic law.

In sharp contrast to other Sufi orders, the Nakşbandis

did not “engage in any outward performance” of their

zikr,

“the act by

which” Sufis meditated and sought “a union with God.” Instead, they engaged in

what they called, the silent

zikr,

as they believed that “the sort of

physical exercise characteristic of other order’s practice” of

zikr

was “theatrical

diversion from the true purpose of the act.” Also unlike other Sufi orders, the

Nakşbandis did not “have a long process of spiritual internship that

required those seeking to join the order to pursue a series of stages under the

guidance of a master before being judged worthy of admittance.” They believed

that a person only approached the order for admittance if he had already

reached a sufficient level of religious enlightenment internally and thus knew

that he was ready.

At times, the enormous power and popularity of the Nakşbandiyya

order ignited the jealousy and insecurity of Ottoman sultans. For example, in

1639, Murad IV “executed a şeyh of the

Nakşbandi

order of

dervishes, called Mahmud, who had grown too influential.” Despite the sporadic

persecution of the order, the Nakşbandis continued with their missionary

activities and spread the teachings of the order to the four corners of the

Ottoman Empire. The order “received a major boost from the teachings of Sheikh

Ziya al-Din Khalid (d. 1827),” who “was a Kurd from the Shahrizor district in

present-day Iraq.” He “rejected the anti-Sufi stance” of radical Muslim

reformers such as Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1791), the founder of the

Wahhabi movement in Arabia, who “condemned all Sufis as heretics,” but the

sheikh also criticized “what he believed to be the divergence from ‘true’ Islam

that most Sufi orders of his day represented.” Sheikh Khaled “saw his mission

as nothing short of the revival of Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire through

strict adherence to Islamic law, grounded in a certainty of purpose that could

only come to the believer through the mystical experience.” His movement gained

popular support among the masses. In particular, the order played an important

role in shaping the culture of the Kurdish-populated region in southeastern

Anatolia, northern Iraq, and northern Syria.

Many among the elite and the subject classes viewed the

Sufi masters as holy men who possessed miraculous powers. When a Sufi master of

great standing appeared in a town, townspeople rushed to touch or kiss the hem

of his mantle or skirt, or even his feet. The tombs of Sufi masters were places

of pilgrimage. When a Sufi

şeyh

passed away, the tomb would be

enclosed and a dome was built over it, attracting pilgrims from near and far

away lands. Cults and myths often arose around the tomb of a Sufi master who

was venerated for his spiritual purity and power. In order to attract the

attention and blessings of a saint or Sufi master buried in a tomb, pious

visitors, the sick, the ailing, impotent men, women unable to bear children,

pregnant women fearful of complications in childbirth, and mothers pleading for

a cure for their children’s infirmity offered prayers and supplications by

tying scraps of material, “shreds of cotton, woolen, and silk morsels of ribbon

and tape” to the railings of the mausoleum or the nearby bushes and trees. Many

lit candles as they pleaded for a cure, while others donated metal candelabra

or carpets for the floor of the mausoleum as a sign of their humility and

devotion. Some who could not find a remedy to their illness slept near or on a

tomb for a few hours or up to forty days if their ailment was serious. At

times, even trees, rocks, or fountains in the garden of the shrine became holy

objects with magical power.