Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (14 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

When Mehmed II captured Constantinople, the city lay in

ruin and the population had been decimated by naval blockade and warfare. The

sultan did not, however, wish to rule over a city of ruins. According to the

chronicler Aşikpaşazade, Mehmed II appointed a new city commandant

and sent his agents to various provinces, declaring that “whoever wishes, let

him come, and let him become owners of houses, vineyards and gardens in

Istanbul,” and to whomever came, the Ottoman government gave what it had

promised, but even this act of generosity was not sufficient to repopulate the

city. Thus, the sultan

gave orders to dispatch families, both rich and poor, from

every province. The Sultan’s servants were sent with orders to Kadis and

commandants of every province, and in accordance with their orders conscribed

and brought very many families. Houses were also given to these new arrivals,

and this time the city began to be repeopled . . . They began to build mosques.

Some of them built dervish convents, some of them private houses, and the city

returned to its previous state. . . . The sultan built eight medreses with a

great cathedral mosque in their midst, and facing the mosque a fine hospice and

a hospital, and at the side of the eight medreses, he built eight more small

medreses, to house the students.

The Ottoman state frequently moved Turcoman tribal groups

from Anatolia and settled them in the newly captured towns and villages of the

Balkans. Jews, Greeks, and Armenians also followed Ottoman armies and opened

businesses in the newly conquered towns. The new settlers injected new blood

into the urban economies, increased the population, and diversified the ethnic,

linguistic, and religious composition of the region. In these new Ottoman

administrative centers, government officials, members of the religious classes,

commanders of the army, and soldiers of the local garrison performed the daily

work of running a vast empire. These officials included government agents who

supervised tax collection; a

kadi,

or a judge in a religious court; the

sipahis

and their warden; the janissaries and their commander; the wardens of the

fortress; the market inspector; the toll collector; the poll-tax official; the

customs inspector; the chief engineer; the chief architect; the mayor; as well

as the local notables and dignitaries. Always with the new Muslim populations

came the ulema of the Hanafi School of Islamic law, who acted as the chief

muftis, or the officially appointed interpreters of the Islamic law. The influx

of Ottoman officials, administrators, and army officers, as well as new

settlers from Anatolia, created a new Muslim majority in many urban centers of

the Balkans. By 1530, Muslims constituted 90 percent of the population of

Larissa in Thessaly (Greece), 61 percent in Serres (northern Greece), 75

percent in Monastir and Skopje (Macedonia), and 66 percent in Sofia (Bulgaria).

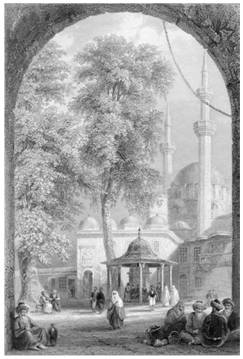

Court of the Mosque of Eyoub

(Eyub). William H. Bartlett. From Julie Pardoe,

The Beauties of the

Bosphorus

(London: 1839).

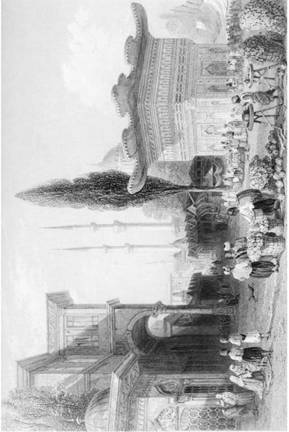

Fountain and market at Tophannè

(Tophane). William H. Bartlett. From Julie Pardoe,

The Beauties of the

Bosphorus

(London: 1839).

VAKIFS

In addition to the sultan, Ottoman officials, dignitaries,

and local notables built and endowed new mosques, schools, bathhouses, bridges,

fountains, and

derviş

convents that came to dominate the urban

landscape. The speed by which these new buildings were completed, suggested not

only plentiful supply of skilled labor and highly developed architectural

traditions, but the sufficient and ready means necessary to fund such projects

through to completion more reliably and much more quickly than European states

could manage at this time.

The true vehicle of Ottoman urban renewal was the pious

foundation, or the

vakif.

By foregoing the revenues from rents on shops

and land and instead directing them into a pious foundation, the founder of a

vakif

relinquished his ownership of the property and its resulting income, but in

return secured blessings in his own afterlife and in the earthly lives of his

children and heirs. Ottoman sultans and their government officials built

mosques, schools, hospitals, water installations, roads, and bridges, as well

as “institutions, which provided revenue for their upkeep, such as an inn,

market, caravanserai, bathhouse, mill, dye house, slaughter house or soup

kitchen” supported by

vakifs.

The charitable institutions were “usually

grouped around a mosque, while the commercial establishments stood nearby or in

some suitably active place.” Regardless of their physical location, they played

an important role in the civic life of the city by providing essential public

services as well as offering goods and services for sale.

Vakifs

also

financed Sufi convents, as well as water wells and fountains that kept the city

alive and provided water for ablution. They also fostered trade by funding the

construction and maintenance of bridges and ferries.

BAZAARS AND BEDESTANS

Outside the imperial palace, urban life focused on the

marketplace. Every “Ottoman city had a market district, known in Arabic as

suq

and in Turkish as

çarşi

where both the manufacture and sale of

goods were centralized.” This was an important public space in any Ottoman

city, and it was replicated across the empire. Markets served as the center for

the people’s social and economic life. The majority of large urban markets also

“had an inner market, known as

bedestan,

which could be closed off at

night or in times of trouble.” To attract merchants and craftsmen to their

domain, Ottoman sultans built covered markets with

bedestans

in the

cities they conquered. These markets, as well as inns or caravanserais, “served

as lodgings for merchants” who “stored their valuable goods in special vaults

reserved for them” at “these establishments.” At times,

bedestans

were

used for storing “grains and other agricultural goods collected as product-tax

by the representatives of the central administration.”

Bedestans

also “included

shops where local and long-distance merchants exchanged their goods.” The large

covered markets were usually surrounded by wide streets, gardens, and running

springs on all sides.

The covered bazaar of Istanbul (

kapali çarşisi)

,

located in the center of the old city, was a “city within a city, containing

arcaded streets, numerous lanes and alleys, squares and fountains, all enclosed

within high protecting walls, and covered by a vaulted roof studded with

hundreds of cupolas, through which penetrated a subdued light.” One

19th-century European visitor explained that the covered bazaar was “composed

of a cluster of streets, of such extent and number as to resemble a small

covered town, the roof being supported by arches of solid masonry,” with “a

narrow gallery, slightly fenced by a wooden rail,” occasionally connecting “these

arches.”

The

kapali çarşisi

was designed and developed

by Mehmed II, the conqueror of Constantinople, who “built more than 800 shops

in the central location that was to become the covered bazaar, mainly shops of

cloth merchants and tailors.” By the beginning of the 18th century, the bazaar

contained three thousand shops, and by the end of the 19th century, four

thousand. Aside from shops, the covered bazaar had its own mosque, fountains,

public bathhouse, school, coffeehouses, and warehouses. Shoppers could enter

its 61 narrow streets and lanes through 18 gates. Those visiting the covered

bazaar for the first time frequently got lost or confused.

Within the covered bazaar, there were distinct quarters and

sections for each trade and craft. Manufacturers such as “goldsmiths,

shoemakers, carpet merchants, and those who sold coats, furniture, jewelry,

furs, cutlery, old clothes, cosmetics, hats, and almost any other kind of goods

gathered together in their own sections of the bazaar.” The merchants and

shopkeepers sat cross-legged on carpets in front of their shops and wore large

turbans on their heads. Jewish, Greek, and Armenian traders and shopkeepers

dressed and worked like Muslim merchants. Despite the best efforts of several

religious sultans to prevent non-Muslim merchants from wearing the same clothes

as the Muslim merchants, the Christian and Jewish traders continued to dress

and act like their Muslim counterparts.

Outside

kapali çarşisi,

there were also

specialized bazaars where particular goods or products were exchanged or sold.

Thus, the fish market of Istanbul offered a wide variety of fish taken, with net

or line, by fishermen of the Black Sea, Sea of Marmara, the Golden Horn, and

the Bosphorus, while the Egyptian Market served as the great depot of spices

and drugs. Here the merchants sold such goods and products as “cinnamon,

gunpowder, rabbit fat, pine gum, peach-pit powder, sesame seeds, sarsaparilla

root, aloe, saffron, liquorice root, donkey’s milk and parsley seeds, all to be

used as folk remedies.”

Marketplaces and bazaars served as the centers of the

city’s commercial life. Men of all nationalities and religious affiliations,

along with veiled women, many attended by servants, bargained with merchants

and shopkeepers. Although “the markets were largely a part of the male sphere

of Ottoman society, women could be found there as well.” Indeed, “poor women

and peasant women hawked produce they grew themselves or items they made, such

as embroidered towels.” Other women, “most commonly Jews, acted as peddlers

carrying wares in the upper-class neighborhoods, visiting the harems and

offering goods to women who were barred by social custom from going to the

public markets themselves.” Among “the wealthy classes, it was not unusual for

women” to own shops. In “such cases, however, social custom did not allow the

women to deal directly with men from outside their families,” and they were

forced to leave “the actual daily running of the business” to “a male relative.”

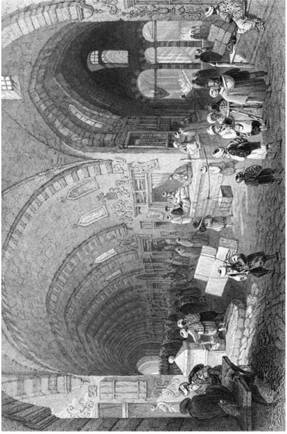

Great Avenue in the

tchartchi

(covered bazaar). William H. Bartlett. From Julie Pardoe,

The Beauties

of the Bosphorus

(London: 1839).

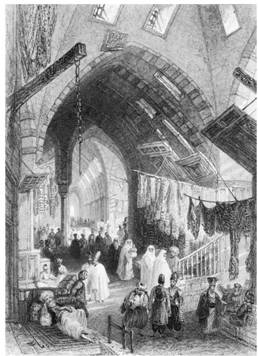

A scene in the

tchartchi

(covered

bazaar). William H. Bartlett. From Julie Pardoe,

The Beauties of the

Bosphorus

(London: 1839).

MERCHANTS AND GUILDS

In the Ottoman social hierarchy, the merchants and

craftsmen stood below the members of the government and the ruling elite. They

were required to dress in their own unique clothes and were prohibited from

wearing the garments of the ruling classes. In all Ottoman cities, local

manufacturers were organized into guilds that produced consumer goods and

handled local trade, while wealthy and well-connected merchants controlled

long-distance commerce.

MERCHANTS

There were two categories of merchants in the Ottoman

Empire: those who functioned as local traders, buying and selling goods

produced by the guilds, and the

tüccar

or

bazirgan,

who were

involved in long-distance and overseas trade. The local traders formed a

distinct category within the guilds and were, therefore, subject to the same

regulations as the handicraftsmen. Those who were involved in long-distance

trade were not subject to guild regulations. Though not part of the ruling

elite, the wealthy merchants who connected the markets of the Ottoman Empire

with those of Europe and “the Orient” enjoyed enormous power and influence

among government officials, many of whom invested in international trading

ventures.

The

tüccar

performed several important functions in

the Ottoman society and economy. The “most important of these was the

distribution of raw material, food, and finished goods throughout the empire”

and beyond. In addition to trade within the empire, the

tüccar

imported

and exported a variety of luxury goods. All these commercial activities

resulted in significant contributions of customs and tolls to the imperial

treasury. The

tüccar

involved themselves in large-scale exchange of

goods or, in the case of luxuries, items of unusually high value.

In the Ottoman society, the few existing industries were

controlled either by the state or the guilds, and cash was concentrated in the

palace and among the small ruling elite. Those who had amassed large fortunes

in gold and silver invested in commercial enterprises organized by wealthy

merchants. Palace officials, provincial governors and notables, as well as the

powerful religious endowments, invested their money through the merchants in

mudaraba,

or in a commercial enterprise or major trading venture suitable for

investment by a man of wealth and power.

Wealthy merchants, who mostly operated from a

bedestan,

traded

in luxury goods such as “jewels, expensive textiles, spices, dyes, and

perfumes.” Their fortunes in gold and silver coin, as well as their ownership

of slaves and high-quality textiles, were the outer signs of their enormous

power and prestige in the urban communities of the Ottoman Empire. While “the

merchants were among the most important and influential inhabitants of every

city, they were also among the least popular.” Given “the profession and the

understanding of the market economy” of these businessmen, “it is not amazing

that they always aimed to maximize their profit involving speculative ventures

of the simplest kind like buying cheap and selling high.” Because “this

speculative activity included food and raw materials,” the merchants “were

blamed for all shortages that occurred occasionally.” Their reputation and

standing “sank even lower in the latter period when their wealth permitted them

to go into such professions as tax farming, which was certainly very unpopular

with the population at large.” Beginning in the second half of the 16th

century, the power of the long-distance traders began to decline as European

merchant ships came to dominate the overseas trade and as “families descended

from kapikulu officers [slaves of the sultan serving as soldiers or

administrative at the palace] gained control of tax-farming and began to

dominate the towns, both socially and politically.”