Cyclogeography (10 page)

Authors: Jon Day

Nevertheless the utopian schemes of the modernist cyclists seemed pretty far away from the world Sinclair described, and I wanted to know what he thought of the future of cycling. Could it be reclaimed as a

subversive activity, despite the branding, despite the hugely inflated bicycling costs, despite the surveillance of Boris bike tracking and the potential for political appropriation? Was David Cameron’s much-publicised cycling commute to the Commons (during which he was followed by a chauffeur-driven car containing a change of clothes and his security detail) the death-knell for any kind of cycling utopianism? Was there any hope for a resurgent cyclogeographic tradition as radical as Jarry’s? ‘I’m not encouraged to get back on a bike,’ he said. ‘I might do from time to time. I might do in another place. The south coast. You can get that much further much more easily. But I hate the idea of having to lock it up, carrying this great thing because otherwise it’s gone. I used to cycle to Victoria Park, leave the bike in the bushes, run round the park and cycle home. Now, I think you wouldn’t be able to take your eyes off it, unless you’ve got a complete wreck. Even the wrecks are desirable now. There’s a shop – I don’t know if it’s still there – that used to specialise in that sort of retro look. Tweedy jackets and wicker baskets. It’s bizarre.’

Sinclair was winding down. He’d said his piece. He was interested in bicycle couriering, in the endgame of the career. ‘What’s an old courier supposed to do?’ he asked me. They become controllers, I said, or cabbies. Or they die on the road. Forty seems to be the point at which the body wants to give up. ‘That’s the nice thing about walking, you can go on a bit longer’, he said.

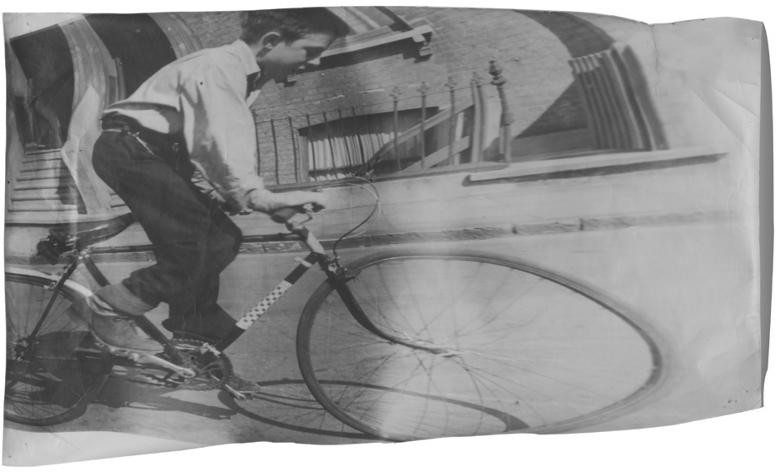

Inspired by my encounter with Sinclair, I wanted to get out of London, to the edge of things. He had tipped me off about Nigel Henderson, an artist and photographer who had lived in Bethnal Green after the war and made a series of what he called ‘stressed photographs’ of boys riding their bikes around the East End in the 50s and 60s.

Henderson was interested in the way his photographic images captured something of the movement of the cyclists themselves, the way in which an apparently objective record of an action could be manipulated to suggest the action described. It was a curious form of subjective indexicality. ‘I noticed,’ Henderson explained:

that when I had an actual negative that interested me (let’s say a boy on a bicycle) I could sometimes enrich the impact of the image by slanting the paper under the enlarger projecting lens […] If I pleated the paper horizontally I could create a pattern of stress which further animated the situation by putting the wheels and frame ‘through it’ as it were and creating an identification with the boys’ efforts and the tension of the wheels and frame in a somewhat ‘Futurist’ way.

I was fascinated by Henderson’s stressed photographs of cyclists, and Sinclair had told me about another potential cyclogeographic

dérive

, one that seemed

to fulfil the themes of cycling as a kind of topographical mapping. It was to follow Henderson on a ride down the Northern Sewage Outfall, part of the great anti-cholera sewer system built by Joseph Bazelgette in the 1860s, which runs from Wick Lane in Hackney to Beckton in east London. Sinclair had told me that Henderson used regularly to stalk the great pipe, walking and cycling along its length, exploring the territory as he went. No one was on a bicycle then at all, he had said, just Henderson and the odd fisherman.

Nigel Henderson’s stressed photograph of a cyclist

One spring day I tried to follow the line described by the outfall – now sanitised and branded as a cycle friendly ‘greenway’ – from the River Lea, near to where I lived, to Beckton. It wasn’t a satisfactory journey. After I’d wrangled with the guts of the Olympic site, where bored security guards manned every junction,

turning me back, and where the razor-wired watchtowers made the landscape look like something from a Second World War movie, I found the greenway. The ride along the length of the pipe was uneventful, save for the occasional whiffs of piss and shit you got along the way, drifting from the pipe. The landscape was sparse, post-industrial.

When I got to Beckton I climbed the Beckton Alps, imagining myself climbing one of the great cols – Alpe d’Huez, perhaps, or Mont Ventoux, where the British cyclist Tommy Simpson died in the heat, far above the tree line, during the 1967 Tour de France, his body broken by fatigue and jumped up on amphetamines and brandy. In the distance stood the old gas works, used as a stand-in for the Vietnamese city of Huê´ during the filming of Stanley Kubrick’s

Full Metal Jacket

. The place still had an air of scorched earth about it. Burnt-out park benches lined the route, and many of the tracks were fenced off. Ten thousand people used to work here, manning the gas works, but now it lies largely empty. I climbed the weaving path that winds up the hill to its highest point and clambered through a gap in the fence, where a couple were kissing in the shadow of a fence across which several large crosses of St George had been painted. They didn’t welcome the intrusion, and so I slipped away, back along the pipe, back into the city.

Couriering is constrained navigation. You’re constrained by the demands of commerce – by the companies that book the work, by the layout of the industrial sectors of the city (PR, design and fashion in the east, media and commerce in the middle, publishing and boutique retail in the west) – but also by the shapes and contours of the roads themselves. Maps are historical records of these constraints, which change over time. In the city especially the memories contained in maps are only tentative. Roads become blocked and one-way systems are enforced, seemingly overnight, in order to accommodate the long-term projects that keep the city moving. For the past few years Crossrail has been redrawing the London map around itself, and a huge development in Victoria has channelled cyclists and drivers through vast metal channels in a temporary re-mapping of the area, killing cyclists implacably as it goes.

The London map, as experienced by its cyclists, is created around these temporary hot spots and reworkings, and thus is inherently fluid. There is no such thing as an accurate map of London: there are instead only records of what it was, or imagined projections of what it might become. Many maps of London include streets that have never existed, even in the eyes of the planners. ‘Trap Streets’ they’re called, and they’re used to catch out would-be copyright infringers, built-in errors used to assert their maker’s intellectual property.

For couriers maps are essential tools of the trade, but they are always provisional and partial. Most

couriers use the

A–Z

, but more and more riders these days use their smartphones to navigate. The maps used by some of the older riders are personal documents that they’ve amended with scribbled hieroglyphs: notes on buildings that only let you in through the back entrance or only at certain times of day; footnotes recording the rhythms and reliability of particular goods lifts; Post-its warning of the presence of aggressive postroom workers at various locations across the city.

London’s most famous cartographer is, or at any rate should be, Phyllis Pearsall, the creator of the

A–Z.

The story of Pearsall’s map – conceived by the young artist in 1935 as she wandered Belgravia looking for a party armed only with an inadequate Ordinance Survey map of the area – is told as an epic, but it’s really a love story. And, like all love stories, there is a strong element of mythology to it. Struck by the insufficiency of the existing maps of London, it is said that Pearsall spent a year walking every one of London’s twenty thousand streets for ten hours a day. By night she drew her map.

One of her great innovations was to obtain a list of street-name changes from the London County Council in order to update her new map of London (a box of ‘T’s blew out of the window of her office onto High Holborn, she later recalled, and so in the first

A–Z

Trafalgar Square didn’t have an entry in the index). Eventually she conquered London’s 3,000 miles of streets and inscribed them all onto paper. Roads took

precedence, in scale, over buildings and green spaces. If Harry Beck’s tube map was a work of abstraction, Pearsall’s map was an impressionist masterpiece. It was a difficult book to sell at first, but eventually W. H. Smith agreed to stock her map, the first edition of which Pearsall delivered to shops herself in a wheelbarrow. The

A–Z

was a map which had governed my daily experience of the city for years, but now I wanted to leave it behind, to find out what lay beyond it.

Almost fifty years ago, while he was still a student at Central St Martin’s School of Art, the artist Richard Long embarked on a different kind of mapping: a bicycle ride from WC1 to Cambridgeshire. A photo of him about to set off shows a young, steely-eyed man carrying a rucksack and standing beside his road bike, a simple six-speed machine with mud guards and dropped handlebars. To the top tube of his road bike were tied a bundle of sticks he would use to mark out his way and record his journey.

Long’s ride took him three days of largely nonstop cycling. He pedalled out of London, through Ely, Tring and Cambridge. He cycled along A roads and canal towpaths, along country tracks and across muddy fields. At sixteen locations along his route he drove one of his stakes into the ground. ‘Starting from the entrance of St Martin’s in London,’ he later recalled:

and carrying the components of the sculpture strapped to my bicycle, I commenced a more-or-less continuous day-night-day-night cycle ride around the counties to the north of London, ending back at my flat in the East End. At random places and times along the way I left one part of the work at each place. Each consisted of a yellow painted vertical piece of wood stuck into the ground, with a blue horizontal crosspiece at the top. They were left in gardens, on verges or village greens, in fields etc.

Near the location of each stake Long attached a notice which his mother had typed for him on her typewriter. The notice read:

THIS IS ONE PART OF A PIECE OF SCULPTURE WHICH SURROUNDS AN AREA OF 2401 SQ. MILES. THERE ARE FIFTEEN OTHER SIMILAR PARTS, PLACED IRREGULARLY.

With this simple yet radical act Long broke free from the confines of the gallery, and from the constraints of traditional sculpture. Long marked his progress and recorded his route on a map, which is all that’s left of the work.

Originally Long’s map was part of a triptych, locating the local journey he’d made in progressively more abstract space: first in relation to an OS map of the area, then in relation to the country itself, and finally in the context of a map of the world. Much of Long’s art is about reclamation. A few months before he made his

cycling sculpture Long had hitchhiked from St Martin’s back to his home in Bristol, stopping somewhere in the Wiltshire countryside before finding a field and walked up and down in the damp grass. He took a photograph of the resulting track, which he called

A Line Made by Walking.

He has been walking ever since – on moors, up mountains, over deserts and across the frozen glaciers of Antarctica – and you can tell. At sixty-nine, Long is lithe and energetic, a looming presence with the slightly weathered air of a country vet.

For most of his career Long has used natural materials to make his works, stones arranged on the floors of galleries or mud applied directly to the walls. In the 1970s he began making sculptures using River Avon mud – still his favoured material – and he’s since become something of ‘a mud expert’. With his walking works he reclaims the act of movement itself as a form of artistic activity. With his mud works he reclaims an elemental material. His cycling sculptures, which he’s made several of over the years, reclaim the map as something in its own right: not as a reference to the world but as an abstract shape with some intrinsic beauty, suggesting but not describing the journey it describes. His work evokes the poetry of travel rather than its prose. Much of his art is about the spaces in between stopping points, about bodies and measurements, about moving through time and space and leaving traces of this movement only in faintly algebraic commemorations of the routes taken or the work

done.

His subsequent work has occupied that fertile territory between an idea and its actualisation, between the act and its record. Often he documents his walking sculptures as maps, prints and photographs, narrating the story of them rather than reproducing the journeys themselves. Many of his walks are recorded only as text works, haiku-like prose poems, and talking to Long is a bit like encountering one of these enigmatic pieces. Underneath it all is an understanding that ideas can be beautiful in and of themselves. Long’s

Cycling Sculpture, 1–3 December 1967

now only exists – perhaps only ever did exist – in map form. The shape marked out by the points he traced doesn’t resolve into anything else. As a map it is vague, stripped of place-names, roads and topographical features. It is the record of a dreamt or unreal journey.