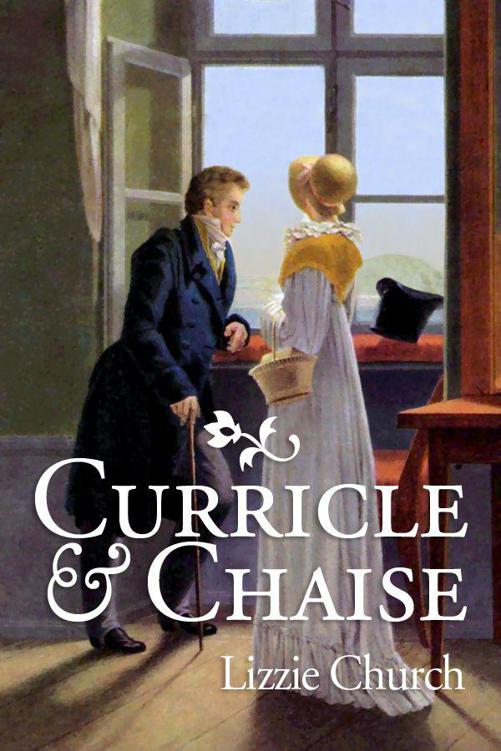

Curricle & Chaise

Authors: Lizzie Church

Curricle &

Chaise first published 2012. Copyright © Lizzie Church 2012 - all rights reserved.

Cover desi

gn and illustration by John Amy

www.ebookdesigner.co.uk

, b

ased on the painting 'Couple at the Window' by Georg Friedrich Kersting (1785-1847)

When Mrs Thomas Barrington was so inconsiderate as to depart this world without so much as a ‘by your leave’, leaving two daughters to burden their aunts and precious little else to cover their maintenance, their futures looked very uncertain indee

d. Of course, it was entirely natural that two

young ladies of 19 and 7

would

feel

bereft at the loss of their mama, but to Miss Lydia and Miss Susan Barrington their change in circumstances demanded a total and somewhat painful adjustment to their whole way

of life. With their father less than

two years dead and no male relative available to render them assistance

it quickly became apparent that

they must

learn to

shift for themselves. Even this might have proved tolerable. After all, Lydia was an independent sort of a girl, more than capable of holding her

own against importunate trades

men

,

and more than

ha

ppy to bring her younger sister up on

her own

. It would not do, however. The state in which Lydia discovered the family affairs made independent existence quite out of the question. In spite of all her best efforts, within a few months of her mama’s death, and scarcely out of full mourning, it became apparent to her that there was nothing to be done but to acknowledge the inevitable and appeal to her relations for help.

The girls’ circumstances occasioned some debate amongst the relatives in question – two aunts, both sisters of Mrs Barrington. Elizabeth, the younger, was happily married to a dedicated but impoverished clergyman in Surrey. The other, Mary, was a somewhat hard-faced female on the wrong side of forty. She had made an excellent marriage in her more endearing youth and now lived in style and the constant vapours in the Abdale mansion in Middlesex

. Elizabeth, indeed, despite a

delicate financial situation

, tiny house

and a rather

fearful regard for her spirited

elder niece would have been more than pleased to offer both girls a home

. B

ut Mary would have none of it, talked persuasively of duty (and thought secretly of the benefit

that

Lydia could bring to the rather constrained society of Abdale House, and more particularly to the care of her most expensive cups and plates) and had nimbly requisitioned the elder of the two almost before Lydia had requested her assistance.

This left Elizabeth with young Susan – a somewhat ponderous,

slow child

of very few words and

with a rather perplex

ing air of never being

quite aware of what

was going on

,

for whom, her sister feared, life would always be

something of

a struggle.

It was several months before the aspirations of either aunt could be met, however. Lydia was determined to salvage what property she could, more for her sister’s sake than her own, and she fought desperately to retain some semblance of independence to the end. But what hope of success could a young lady of gentle birth and no influential friends expect in the face of determined creditors? There was no way in which the tradesmen could wait for their bills to be paid. They had only waited until now out of respect firstly for dear Lydia’s poor

, unfortunate

papa, and la

tterly for Miss Lydia’s highly esteemed

mama

,

and

there was now nothing to restrain

them from taking over the premises immediately. The skirmish lost (though the bills paid) Lydia gave way in as gracious a manner as she could muster, packed her sister’s trunk and her own, and summoned the assistance of her uncle – which materialised in due course in the form of a chaise and four.

And so it was that, on a bleak November day in the year 1810, Miss Lydia Barrington found herself huddled in her Uncle Abdale’s second best carriage, jolting alon

g the turnpike towards her new home

.

She had taken a

detour

on the way from

Bradbury

so that she could

deliver Susan into Elizabeth’s welcoming arms in Surrey and after a short stay of a couple of days (which she had spent primarily in assisting her sister to unpack, settle in and become used to the extremely constrained surroundings of her cupboard-sized bedroom in the vicarage attic) she had set

off once more, firstly in the S

tage to London (a city which she would like to have had the chance to explore more thoroughly) and latterly in the chaise.

It was a long journey and she was feeling miserable. Not that Lydia was one normally to succumb to the di

smals. She had a cheerful disposition

as well as a somewhat fiery temper, but her changed situation, and the weather, and the effects of a cold that simply would not go away,

concerns abo

ut Susan,

and

what she, Lydia, could possibly do with her life - and

more tha

n anything, the prospect of living

with a

unt Abdale

,

were sufficient to put the dampers on what she would normally have found an interesting journey. She was actually feeling a little sorry for herself – quite a new sensation for her, and one that she was finding had little to recommend it. For two years now she had been used to the freedom and responsibility of running her mama’s house virtually single-handed since her father’s death at the battle of Vimeiro (an event which, on looking back, Lydia was convinced had led to the demise of both of her parents and not just the one). The change from being used to issuing instructions and having her own way, of dealing with servants and trades

men

from day to day, to being dependent on the good offices of an aunt whom she detested (and whose motives in offering her a home seemed singularly suspect) and cousins whom she had not seen for nigh on

six

years, was not one to which she was looking forward with much relish. So she felt miserable and

hard done by

, clutching her grey silk handkerchief and shivering perceptibly in the draughty carriage. It wasn’t until the coachman turned to speak

to her

that she realised how far they had come.

‘If you care to look to the right, Miss, you will just see Abdale House

over there,

beyond the trees.’

Sure enough, silhouetted against the grey November sky, Lydia could just make out the familiar square form of Abdale House, planted s

olidly

in its

magnificent

park. And then the carriage swung round into the driveway, between two sturdy iron gates and up the avenue of limes, an

d within a very few minutes

they had pulled up on the gravel frontage under the imposing portico and she was being handed down at last.

Her welcome to Abdale was not exactly effusive. Indeed, it was scarcely a welcome at all, the housekeeper being the only soul to ma

terialise

at the sound of the bell, and she appearing more than usually severe in the gloominess of the hall.

‘

It is good to see you again, Mrs Arthur,’ said Lydia, trying to ignore the rather upturned nose of the upright figure before her.

‘I hope I find you well?’

Mrs Arthur emitted a sniff designed to convey her own superiority over all dependent relatives, however polite and well bred they may be. ‘Master and family is all gone out,’ she returned. ‘I can show you to your room, if you like’.

If Lydia was surprised she did not show it. Instead she followed her guide up the broad staircase, trusting that the coachman would see to the removal of her trunk. Mrs Arthur led her past the guest rooms and up a second flight of stairs, approaching the door of what Lydia well remembered to be

the former governess’s room. Mrs Arthur

flung open the door with another condescending sniff and turned back along the corridor before Lydia could even step inside. The room was cold and gloomy; the grate contained no fire. Only the fact that the bed was made up indicated that she was, indeed, expected there at all.

Lydia looked around the room pensively as the housekeeper stalked away. She felt acutely aware of her uncomfortable position here at Abdale. She had no doubt that her situation had been made well known to the servants, and that this reception provided just a taste of things to come.

It was some time before she had a chance to find out, however, as it was after eleven the next morning before Mrs Abdale appeared in the breakfast room, rather plump in her mauve muslin robe. She stopped in the doorway and eyed her niece narrowly for a moment before advancing into the room as stiffly as her somewhat rotund form would a

llow. In the

six

years since she had last seen her niece

Lydia had metamorphos

ed f

rom a somewhat thin, pasty four

teen year old into an elegant and stunningly beautiful young lady, with a trim but shapely fi

gure. Her shining dark chestnut

locks refused to subject themselves to the confines of a half-mourning cap – an item of apparel which would

have rendered any less attractive

a wearer positively plain, but which only su

cceeded in making Lydia

appear even more beautiful than normal.

Mrs Abdale, in contrast, was anything but shapely and trim.

Unaccountably, the image of her late mama’s pet pug dog (an animal with whom Lydia had enjoyed a somewhat adversarial relationship until its felicitous if untimely demise at the wheel of a carriage and four) fleetingly entered Lydia’s brain

as she looked at her. She endeavoured to set

t

his

aside as she bobbed a demure curtsey to her aunt.

‘My dear Lydia,’ effused Mrs Abdale,

sailing into the room and

allowing her niece the liberty of a peck on the cheek before proceeding to pile a plate with ham and cheese from the sideboard. ‘In what melancholy circumstances we find ourselves, indeed. And to think that the last time we met my poor

dear sister Barrington seemed

in

as good

health and lively as ever. Such a shock as it was. Why, it quite laid me up for a full se’ennight or more.’

‘We are all very sorry about it, I’m sure, ma’am.’

‘And to leave you alone in the world, entirely destitute, so Abdale assures me. How dreadful. You are to be quite a burden on us, I fear.’

Lydia inclined her head and said nothing, concentrating on the pattern of the carpet instead.

‘Yet I was quite astonished to hear of her sad passing away. Your mama was always a sorry, impractical sort of a child but she was never of so sickly a disposition as I – why, had I died in her stead I should scarcely have been more surprised.’