Cross and Scepter (20 page)

Authors: Sverre Bagge

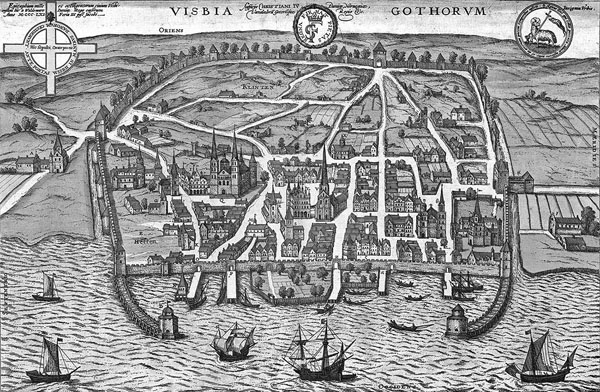

Figure 13.

Sixteenth-century city plan of Visby on Gotland (Sweden). Only half of the area inside the wall has urban settlement; the upper part, which is actually a hill, consists of fields. This may be the result of the decline of the town in the later Middle Ages, although it was quite normal for medieval towns to have agricultural areas inside their walls to provide food for the inhabitants. The many stone houses and the large churches indicate that the city was still wealthy. Today, Visby is one of the best-preserved medieval towns in Scandinavia, although, except for the cathedral (no. 2 from the left), all the churches are in ruins. From Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg, eds.

Civitates orbis terrarum

, vol. 5., first edition (Cologne 1572, repr. Cologne, 1898).

There was a considerable expansion of Scandinavian trade during the Middle Ages, which led to closer contact with the rest of Europe, to urbanization, and to the increased use of money; all of which contributed to a substantial economic surplus. Almost all the towns that existed in Scandinavia around 1300 had been founded during the previous 300 years. However, the urbanization trend did not alter the predominantly agrarian character of Scandinavian society. Agriculture was probably more important in the High Middle Ages than in both the previous and the following period. Most of the export consisted of surplus from agriculture and the fisheries, and the greatest exporters were the members of the landed aristocracy. Although the towns were home to a number of indigenous merchants and artisans, export trade was dominated by foreign merchants. Politically, the indigenous merchants were too weak to compete with the landed aristocracy, in contrast to the situation at this period in the most commercialized areas of EuropeâItaly, the Netherlands, and parts of France and Germany.

Bureaucracy or Feudalism?

Thus, the division of power in contemporary societyâat least at the central levelâbecomes a question of the relationship between

the king, the Church, and the secular aristocracy. In contrast to many other recent scholars, R. I. Moore regards the period from 975 to 1225 as crucial for the development of the European state. An ecclesiastical bureaucracy and an intellectual elite developed an increasingly systematic and intolerant doctrine that was imposed on the population, and a distinctive royal bureaucracy resulted in more effective and oppressive government in Europe than in most other contemporary civilizations. Although there arose a class of professional bureaucrats in the king's service in countries like England and particularly France, which to some extent formed a counterweight to the top aristocracy, Moore exaggerates their importance compared to the prelates and the aristocracy. What characterized the political system of Western Europe in the Middle Ages, compared to that of other civilizations, was not the strength of the bureaucracy under the king's direct control, but on the contrary the king's greater dependence on the leading strata of the population, the prelates, nobles, and burghers. This resulted in corruption, inefficiency, and injustice, but it created a certain amount of stability as well, because the state mattered to its most influential inhabitants. This applies even more to Scandinavia. First, there is little evidence of a central administration recruited from men of lower rank who were completely dependent on the king. In most cases, we do not know the social origin of the men in the king's service, but to the extent that we do, they seem mostly to have been recruited from the aristocracy. Second, the central administration was significantly smaller and less developed.

However, we do note movements in the direction of Moore's bureaucracy in Scandinavia from the late twelfth and particularly the thirteenth century onwards. The central administration in Scandinavia, as well as in the rest of Europe, had its origin in the king's household, as the titles of the various officers indicate: “marshal” or “constable” (head of the stable), “steward” (kitchen

manager), etc. These offices continued to exist later in the Middle Ages, but they were sometimes kept vacant. A new officer appears from the late twelfth or early thirteenth century, the “chancellor,” who was responsible for the king's correspondence and kept his records and accounts. The development of the chancery in the following period made the chancellor the most important royal official and gave him a role resembling that of Moore's bureaucrats in England and France. Clerical chancellors played an important part during the authoritarian regimes in Denmark under Erik Klipping and Erik Menved, as well as in Norway under HÃ¥kon V.

The rise of the chancery was of course a result of the increasing use of script in administration from the thirteenth century onwards. The number of letters extant or known to have existed during the most active period of the royal chancery in Norway, the reign of HÃ¥kon V (1299â1319), is twenty per year. The Swedish chancery reached the same figure in the 1330s, while the total number of letters per year in Denmark in the early fourteenth century was eighty. As most of what was written has been lost, these numbers probably represent only a tiny part of what was actually produced. There is also evidence of efforts by the king to attach competent people to his chancery, clerics as well as laymen, for instance the foundation of an organization of royal chapels by King HÃ¥kon V of Norway, and the systematic use of canons for the same purposes in Denmark and Sweden. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the output was anywhere near that of the contemporary English chancery. Henry II (1154â89) already is supposed to have issued 115 letters per year, whereas a dramatic increase took place under his successors, which can be measured in the rise in the amount of wax used per week for sealing: from 3.63 pounds between 1226 and 1230 to 31.90 between 1265 and 1271. It might also be mentioned that the total of all published documents from Norway in the period from about 1000 to 1570,

from institutions as well as individual persons, fills twenty-three large volumes, which represents the majority of the extant material; unprinted letters may fill a few volumes more. This amount is roughly equivalent to the material issued by the English royal chancery over a few decades of the thirteenth century. However, medieval England was “a much governed country,” and the volume of documents both used and preserved was higher there than in any other country north of the Alps. Although far behind England, the Scandinavian countries show a significant rise in the use of script from the thirteenth century onwards, the late-medieval material from Sweden, and particularly Denmark, being significantly more abundant than that from Norway.

The medieval commonplace about the value of writing was that it served to preserve the memory of things that had happened. This is the theme of numerous introductory statements in the royal charters (

arengas

) and is also mentioned in prefaces to historical works. Most obviously, kings, prelates or great lords needed to keep records of their estates and rights to determine whether they received what they were entitled to from their subordinates. The concentration of property in few hands over widely different parts of the country is difficult to imagine without written records; at the least, such concentrations would likely have been less stable. The importance of the preservation of memory also applies to the legal field, where the reforms carried out in the thirteenth century would hardly have been possible without writing. Whereas in the past it would have been difficult to base legal decisions on a broad knowledge of sentences from earlier courts that had dealt with similar cases, precedence could now acquire greater importance than before. The same principle applied to other administrative decisions. Standardized procedures and routines became possible to a greater extent than in an oral society, and the decisions of lower instances could be backed up by the king's confirmation. The introduction of writing also served

to give the elite greater authority as experts on law, religion, and other fields of knowledge, which in turn contributed to further centralization. Most important, even the relatively modest use of script in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries gave the king and the central government a clear advantage over potential rivals in other parts of the country. The king now could make his will known to his officials all over the country and receive reports from them, which gave him an amount of information that none of his potential rivals in other parts of the country could match.

The consistent application of these principles is more characteristic of Early Modern than of medieval government, but already in the thirteenth century, the use of script made it less necessary for the king to be present in person to have his will respected. Kings, bishops, and other leaders now to a greater extent communicated indirectly, through local officials or through the use of script. The king also normally resided in towns, although he moved between a number of them. In Norway, his usual itinerary in the thirteenth century was by ship along the coast between Oslo and Bergen, spending most winters in Bergen. Winter was also the time for the main festivities of the year, the Christmas celebrations, when most of the leading men in the country gathered around the king. Capitals in the modern sense were a later development. In Denmark, Copenhagen developed into the permanent administrative center in the fifteenth century, but the king continued to travel.

There was also a change in the relationship between the king and his subordinates, at least in theory, a change from “friends” to “officials,” that amounted to a degree of what might be termed “bureaucratization.” Like ecclesiastical officers and in contrast to previous usage, they now had clearly defined districts and owed obedience to the king, although there was nothing like the total dependence on him propagated by sources like

The King's Mirror.

Here the models for the royal official or retainer are Old

Testament heroes like Joseph, Mardocheus, and Esther, who remained obedient to their masters no matter how unjustly they were treated, and whose absolute subordination to the king is expressed in the passage where the Father explains the advantage in joining the king's service. When all men in the realm are obliged to do whatever the king demands without receiving anything in return, becoming the king's man and receiving a salary from him will be an unquestionable advantage.

Of course, the whole point in joining the king's service was to get something in return. The king would not convince anyone to serve him unless he rewarded them. However, there is some echo of the ideas in

The King's Mirror

in formulas used in the correspondence between the king of Denmark and members of the aristocracy in his service in the later Middle Ages. The latter clearly emphasize the distance between the king and themselves when addressing him. The king is “the most noble lord and mighty prince,” and the noble addressing him is his servant who owes him “humble, subservient, dutiful, and faithful service.” The king addresses the members of the nobility, like all other subjects, condescendingly as “most dear to Us.” While the nobles address the king in the plural, the king normally addresses them in the singular, the exceptions being men who are particularly prominent or close to him, who are addressed in the plural. Such men are also addressed in other formulas that make clear the king's especial favor. On the other hand, when ordering his men, the king normally uses the term “ask,” although it is plainly implied that it is their duty to perform his “request.” Most probably, this means of address should be read as that of an exalted, gracious lord, so confident in the loyalty of his men that he finds it unnecessary to address them in the language of explicit orders.

This terminology corresponds almost perfectly to the relationship between the king and his men as depicted in

The King's Mirror

. The difference, however, is that these men were not simply subjects; they had entered the king's service voluntarily and were free to leave it as well. Sources of the later Middle Ages give examples of nobles formally renouncing their loyalty to the king. The formality of the act may indicate that it was considered a more drastic step than in the earlier Middle Ages. Moreover, all known examples of such behavior date from periods of crisis or rebellion, when the noble in question could justify his behavior either by the fact that it had proved impossible to serve the king any longer, or because he was taking part in some joint aristocratic resistance to the king. The late-medieval Danish correspondence between the king and the nobles shows a mixture of the new Christian ideology that sees the king as head of state and God's representative on earth, to whom his subjects owe loyal service, and the traditional or feudal ideas of a contract between the king and the individual noble.

Figure 14.

Christoffer II, from his funeral monument in Sorø Abbey Church (Denmark), second half of the fourteenth century. Christoffer was one of the most unsuccessful of Danish kings, but thanks to his more successful son, Valdemar IV, he got an elaborate and beautiful grave monument in bronze, which gives an impression of royal majesty. Photo: Mariusz Pazdziora. Wikimedia Commons.