Crime Seen (19 page)

Authors: Kate Lines

As it neared the time to introduce the legislation, it was proposed to Jim and Anna that the sex offender registry be named Christopher’s Law. Jim later said, “I thought, ‘No, no, you won’t put Christopher’s name on this. This was dealing with sex offenders. It was a sex offender who sexually assaulted and then murdered our son.’ I didn’t want to have his name on that legislation, but then Anna and I talked about it after and she wondered why I was having difficulty. She thought it would be a good legacy and that it would be significant to give some meaning to the work that we had done and for what Christopher had been through.”

And so it was decided that Christopher’s legacy would be much more than his horrible death. In 2001 Ontario proclaimed Bill 31, An Act in Memory of Christopher Stephenson, referred to as “Christopher’s Law.” Ontario was the first and only province in Canada to establish a sex offender registry and within a few years had one of the highest offender registration rates worldwide. Ontario Sex Offender Registry staff and I joined Jim and Anna in continuing to lobby the federal government, and Canada’s National Sex Offender Registry was finally established in 2004.

Jim’s favourite story to tell about his son was about the time when he and Anna were sitting around the kitchen table talking with Christopher and Amanda about what they wanted to be when they grew up. Jim said, “I told Christopher that when I was his age my teacher asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up and I told her I wanted to be a cowboy. Christopher kind of giggled, so I asked him, ‘What do you want to be?’ He said, ‘I want to be a lawyer.’ I asked him, ‘Why do want to be a lawyer?’ Christopher said, ‘Because I want to make laws.’ ”

Christopher wasn’t given a chance to be a lawyer, but the law that bears his name has gone a long way to save others from harm.

CHANGES AND CHANCES

“Maybe who we are isn’t so much about what we do, but rather what we’re capable of when we least expect it.”

Jodi Picoult,

My Sister’s Keeper

A LATE WINTER STORM HAD ROLLED INTO

Ottawa overnight and it was still snowing in the morning when Trapper and I came out the front door of our downtown hotel. Bob was still sleeping and, as usual, I was on the early shift for dog walking, still wearing my pajamas underneath my winter parka and bare feet inside my snow boots. I pulled Trapper across Wellington Street and into the first open space in front of a government building we came to. There couldn’t have been a worse location to be caught short of a poop bag—the snow-covered front lawn of the Supreme Court of Canada. But my violation of the poop-and-scoop law wasn’t the only thing that weighed on my mind that day. I’d been kicking a bit of snow onto all my problems lately and they were just getting worse.

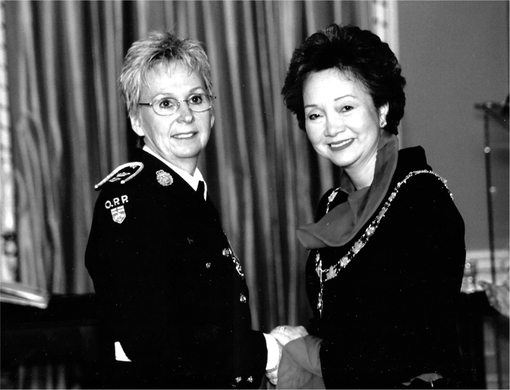

It was April 4, 2003, and Bob and I were in Ottawa as I was receiving the Governor General’s Order of Merit of the Police Forces medal from Adrienne Clarkson. The investiture invitation said I was in the top tenth of 1 percent of the members of police forces for my “exemplary contributions to establishing and promoting concepts in behavioural sciences, concepts that enhance public safety and victim assistance.”

9

I was receiving a lot of accolades from police services and professional groups for my work and to now have my country recognize my service career was such an honour—but at the same time I was feeling a mounting sense of guilt and doubt.

Because the truth was, I didn’t want to do this job anymore. In the course of my workday I’d be taking calls for assistance on homicide, sexual assault and child abuse cases, and when I’d hang up the phone a wave of anxiety would surge up into my chest. Thankfully I had other extremely capable BSS staff that I could assign the cases to. The thought of looking at one more crime report or set of photographs or watching one more videotape made me feel sick to my stomach. Shortly after I returned from Ottawa I stepped down as president of the ICIAF, not wanting to attend any conferences or meetings where these kinds of cases would be discussed. I’d never before experienced such mental and physical fatigue.

Receiving the Governor General’s Order of Merit of the Police Forces medal from Adrienne Clarkson, 2003.

I didn’t see a doctor about what I was experiencing. I’d been working in the business long enough to be able to diagnose myself. Over the years I had helped some of my own staff deal with stress-related health issues and I’d even recently collaborated with Peter Collins in setting up “Project Safeguard” to help those working in undercover assignments deal with the stress in their jobs. I knew what was causing the anxiety and fatigue and I knew what the solution was.

I told no one, not even Bob, about what was going on with me. Frankly, Bob and I weren’t really talking about much of anything anymore. We’d drifted apart and neither of us seemed happy. I thought it might be just a phase and that we’d get through it. While it saddened me that we seemed to be going the way of so many other police marriages, we officially became another statistic when he moved out.

In 2004 I was selected as Police Leader of the Year by the Canadian Police Leadership Forum. It was another enormous honour, but again I didn’t derive as much satisfaction from it as I felt I should have. Right after the announcement I went to my boss and told him I needed to get out of BSS. He was surprised but didn’t ask any questions nor delay in getting me a new assignment.

Within a few weeks I was the director of Intelligence Bureau. I had zero background in intelligence work, other than passing along the odd piece of information to the bureau that I came across when I was working in uniform or undercover. Intelligence had over one hundred staff and I knew little about their work in antiterrorism probes, witness relocation, informant development or intelligence gathering. But the officers and support staff pitched in and got me up to speed. The best part was, even though some days I’d come to work not knowing what the hell I was doing, I felt exhilarated about my job again. I loved the new business I was in, and within weeks felt healthy again and back to my old self.

I attended many of my meetings with my counterparts from other agencies with one of my subject matter experts in tow. The often-long drives to different parts of the province gave me the opportunity to get to know them and their work and for them to get to know me. My predecessors were all male and most had either come up through the ranks or had at least some experience when they took over the director’s position. My own internal intelligence-gathering efforts revealed that one of my managers had more than a little resistance to the idea of me being the new boss and was apparently quite vocal about it—except to my face of course.

One winter day I decided it would be good for me and this manager to take a road trip together. It didn’t go particularly well. En route he told me how he and the other managers in the office were getting together in the near future for an office meeting and to do a little ice fishing. Apparently it was an annual event, apparently I wasn’t invited and apparently I was supposed to pay for their getaway. Well, that wasn’t happening. I countered with a story that I had already arranged a “me and the boys” office meeting at a hotel and spa. I told him that we would have our meetings during the day and I would be booking spa appointments for all of us in the evenings. He told me he didn’t think the guys would like that. I told him they better get used to working for a woman. A period of silence followed and then I told him I was kidding. I’m not sure that he took the joke so well. On the way home, he filled up my unmarked police car with gas and topped up the engine coolant. The next time I was driving the car and needed to spray some washer fluid on my windshield, it squirted out engine coolant instead. Since we eventually ended up working fairly well together after the initial period, I will give him the benefit of the doubt that it was an honest mistake.

In 2006 a uniform position as the chief superintendent in charge of Investigation Support Bureau was advertised, so I threw my hat into the competition ring. I was familiar with the bureau commander job since it was the position that I reported to when I was manager of BSS. I was successful and became the first female commander of Investigation Support Bureau responsible for the specialty areas of forensic identification, electronic and physical surveillance, behavioural sciences, criminal investigations and a relatively new area of expertise, electronic crime.

The Electronic Crime Section (E-Crime) was my steepest learning curve because I knew so little about it. I found out it was no longer as simple as police attending a crime scene, collecting evidence, interviewing witnesses and taking statements. New exploitive opportunities for cybercrimes were being created daily: superviruses; intellectual property fraud; attacks on wireless communications and storage systems; Internet-facilitated identity theft schemes; and online extortion. The crime business had gone global, rarely occurring in one jurisdiction and we were often dealing with multiple offenders residing in different locations around the world.

There were not only new challenges for front-line detectives, but also for my forensic electronic analysts. It seemed every criminal investigation the OPP did had some form of technology-based evidence seized. It was often crucial evidence of the crimes committed:

• Homicide investigators were able to locate the body of a missing child after the murderer’s cellphone pings off a nearby telecommunications tower led them to the area where the child’s remains were located.

• Drug investigators seized a cellphone from an arrested marijuana grower and discovered it contained a photograph of another large crop ready for harvest. A couple of clicks more on the phone and investigators had the GPS coordinates of the photograph and went on over to do a “meet-and-greet” with the harvesters.

• At the murder trial of a police officer shot and killed in the line of duty, a sampling of seized computer data was presented to the jury. A stack of photocopied pages from various Internet sites demonstrated the killer’s interest in weapons in general and especially in the five days prior to killing the officer. The stack was three inches high.

• In a domestic-terrorism investigation, 4.3 terabytes of data were seized as evidence of the crimes committed. Just one terabyte’s worth of stacked paper would be 66,000 miles high.

Having to deal with the potential negative impact of having so much information, some of it being evidence of the crime, was a whole new management issue that I had never dealt with before. And since large segments of the public had minimal knowledge about how computers and the Internet really worked, there were inexhaustible opportunities for criminals to exploit. Particularly vulnerable were children. Police officers and civilian technology analysts were responding with limitless imagination and determination to make the Internet a safer place for kids.

One example of such a creative approach came from the founder of the Toronto Police Service Child Exploitation Section, Paul Gillespie. In 2006 Gillespie took the initiative to email Bill Gates asking for help in battling the online sexual exploitation of children. Microsoft responded with a partnership investment to co-create a new software package to assist in tracking online predators, valued at over $4 million.

10

OPP e-crime programmer Trevor Fairchild developed an award-winning software package for use by child pornography investigators to categorize millions of photographs and movies seized in their investigations. The program was made available free to law enforcement and security agencies worldwide. A co-worker of Trevor’s, programmer and analyst Joseph Versace, developed a software program that monitored peer-to-peer child pornography file sharing in cyberspace twenty-four hours a day, tracking all known images of child pornography being shared online.

And then there were people with good intentions who were using the Internet to try to find information to help family or friends or even strangers. Sometimes they didn’t even know the people they were trying to help. The combined efforts of three web sleuths who’d never met would eventually solve a seventeen-year-old missing person’s case.

Jen was a young woman from the Niagara, New York, area who was searching the Internet trying to find information about her uncle who’d been missing since 1993. Jen’s uncle, Russell, or Rusty as they called him, hadn’t been in touch with his family in over a decade.

Jen had vivid childhood memories of Rusty. “He was a quirky man with a big heart,” she said. “Rusty was a hunter and one time when he was living with my grandmother she told him she would like to have a fresh turkey for Thanksgiving. Rusty brought home an actual live turkey from somewhere that he kept in the basement for two days. Damn did that thing make noise. I liked to pet it. Then it made an appearance on the table for Thanksgiving dinner. I believe that was the year I became a vegetarian.”