Crime Seen (10 page)

Authors: Kate Lines

Roy brought in BSU member Supervisory Special Agent Ken Lanning, to teach the behavioural aspects of sexual exploitation, abduction, abuse and other crimes related to children. Ken was already recognized as one of the world’s leading experts in this field of victimization that he had dedicated his career to since 1973. To say he was passionate about his work was an understatement. I sometimes worried he was going to have a heart attack when he got so agitated discussing topics such as previous generations’ denials of the existence of child abuse and the antiquated and inaccurate notion that “stranger danger” was the greatest threat to children’s safety.

The reality was that children were very often assaulted by people they knew, including their own family members. These sex offenders did not always physically assault their victims in the traditional or legal sense. They often used their authority, trust, grooming techniques and even seduction. They counted on their victims’ responses of confusion, embarrassment, shame and guilt—emotions that prevented them from reporting the abuse or even denying it if confronted.

Ken’s researched-based theories of the different motivations and types of child sex offenders were documented in his publication “Child Molesters: A Behavioral Analysis.”

2

It should be required reading for all involved in the field of sexual victimization of children. When I returned home from Quantico, I never attended a child sexual abuse consultation without having that guide tucked in my briefcase. Ken later included updates on the significant issues created by children and predators having access to the Internet and the use of the Internet for the distribution of child pornography, issues that didn’t exist at the time of my training.

Ken also used in his teaching one of the most comprehensive studies of missing children homicides, later published in “Investigative Case Management for Missing Children Homicides.”

3

One of the statistical tables was starkly revealing: for children who had been abducted and subsequently murdered, 47 percent were dead within one hour of the abduction; 76 percent within three hours; 89 percent within twenty-four hours; 98 percent within seven days; and 100 percent within thirty days. It sent a clear message as to why prompt investigative action by police was so critical in such cases. I cited these statistics many times over my career when police were asking for my help in a child abduction case. I also found them useful when trying to persuade my police bosses and provincial government officials to fund initiatives such as a violent crime tracking system, a geographic profiling program and a provincial sex offender registry.

A key fact to keep in mind was that sexually motivated child abductors and killers spent a significant amount of time fantasizing about taking a child and having sex with them. The actual sexual activity was the centre of the fantasy. The abductors spent little time planning the actual abduction or what they would do with the child when they were finished assaulting them. The abduction was often a circumstance of opportunity: a child left alone for a split second by a distracted parent or a youngster walking home from school or from a play date at a friend’s house. The killers trolled, waited for the opportunity and when it presented itself, they’d strike.

After the assault was over the offenders were faced with what to do with the child. The child would be panic-stricken, often screaming and crying. They would beg to be let go and promised not to tell their parents—that is, if they were even old enough to talk. Panic would set in for the offenders as well. They often had not thought this part through. Killing was one of their choices. Sometimes they didn’t get caught. Sometimes they did.

Those training sessions with Roy and Ken gave me a whole new understanding of sexually assaultive behaviour. Without a doubt it was hardest to work on those cases involving young children as victims, so innocent and vulnerable. I couldn’t even fathom what it would be like to be a parent of a child that was harmed or the worst-possible scenario, taken from them and possibly never know what happened to their child.

TAKEN

“To have a child taken … is to be struck by lightning out of a clear sky.”

—Journalist Bill Cameron in the CBC documentary

Missing

MICHAEL DUNAHEE—THE FIRST CHILD

of Bruce and Crystal—was just a few months away from his fifth birthday. He was a good-natured and outgoing little boy who loved being a big brother to his six-month-old baby sister, Caitlin. On Sunday, March 24, 1991, at 12:30 p.m., Michael was with his family, having just arrived at a school playing field where his mother was to play an afternoon game of touch football. They parked their red Datsun station wagon along the single row of other parked cars on the west side of the playing field. Michael asked if he could go over to the children’s playground area at the side of the school. It was a short distance away, just on the other side of an empty basketball court. He was told that he could, but was not to go off playing elsewhere with the other kids on the playground and to stay within sight. It was the first time Michael had ever been allowed to go to a playground alone, but his parents were no more than a hundred metres away and they would be able to easily see him from the football field. Michael went off toward the playground area as his mom was putting on her football cleats and his dad was settling Caitlin into her stroller.

At the football field Bruce checked on the score of the game in progress and then stepped onto a boulder jutting out of the ground at the side of the field so that he could look over top of the cars and keep an eye on his son. Less than a minute had passed since Michael had left his sight. When Bruce looked over toward the playground area, Michael wasn’t there. He told Crystal that he was going to go look for him. He searched around the school and between the portable classrooms, calling Michael’s name. Bruce ran back to the playing field to tell his wife he couldn’t find Michael. Word spread quickly and the football game was stopped. All of the players and spectators fanned out, searching nearby housing complexes, streets and back lanes. A local home owner, outside cutting his lawn, was asked to call the Victoria Police Department.

That afternoon and evening the police and volunteers searched for a little boy who had wandered off. By morning it had turned into a search by over a hundred officers for a little boy who had surely been abducted. Michael, three feet tall, weighing about fifty pounds, blond hair and blue eyes, freckles on his cheeks, and wearing his favourite

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles

T-shirt, was never seen again.

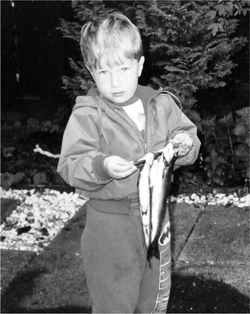

Michael Dunahee’s disappearance rocked Victoria and the wave of anxiety and anguish it created quickly spread across Canada. Every major media outlet in Canada and the northwestern US was covering the story. Posters of Michael were distributed across Canada and the US. Bruce and Crystal Dunahee went on television and pleaded for the safe return of their son. They showed numerous photographs of Michael, one holding a stick with two small fish skewered on it that he had caught with his grandpa. In another he was holding his baby sister. They also played video footage of Michael doing his “boogie” dance on his bed as his mother laughed and looked on.

Although Victoria is British Columbia’s capital city, it has always had a small-town feel. It was now in the spotlight being talked about, not for its spectacular floral gardens or the magnificent nearby mountains, but for its police department undertaking the largest investigation in Canadian history. Child abductions are thankfully rare; this was the first one to occur in Victoria.

Every parent in Victoria at the time was thinking the same thing—this could have been their child who was snatched while they looked the other way for just a moment. No longer were children allowed to walk to school without some kind of supervision. No longer were they allowed to play outside alone. It was a heartbreaking loss of innocence for the city.

After three weeks of investigation and with no firm or promising leads, Victoria detectives contacted the FBI’s BSU for help. As he was responsible for cases that came into the unit from the northwestern parts of the US and Canada, Supervisory Special Agent Steve Etter was assigned as the lead agent on the case.

Steve was just returning to work after a leave of absence and still coming to grips with devastating news of his own. His older daughter, Alexandra, who had been born with a congenital heart defect, had recently died at the age of just two, following surgery. She died on the same day that her new little sister

*

was born.

A funeral service was held for Alexandra in Dale City, just north of Quantico. The church was packed. Just about all of us from the BSU attended. A photograph of Alexandra was displayed at the front of the church. During the service Steve and his wife, Ellen, holding their baby daughter, came to the pulpit to eulogize Alexandra. They played an audio tape of her singing and chatting. They wanted those of us who did not get a chance to meet Alexandra to get to know who she was. I don’t know where they found the strength.

Steve had only been back to work for a few weeks and when I heard he had been assigned a Canadian case, I asked him if I could be involved. It was the first one to come in to the unit from Canada since I’d arrived at Quantico. A few days later I went to pick up the task force investigators from several different BC police agencies at nearby Manassas Regional Airport. They stepped off the private BC government jet loaded down with briefcases, numerous banker’s boxes and a gift of two large fresh salmon packed in ice.

The Quantico trip provided the detectives an opportunity to be out of the limelight for a few days. They had not had a day off in weeks. My offer of some relaxation and beverages was eagerly accepted and we left the airport for a nearby tavern. They told me that they were hopeful that the FBI consultation the next day would bring some new perspectives to their investigation. I let them know we would also be joined by Ken Lanning and gave them an overview of the training I had already received from him.

After a few short hours filled with their sharing what their lives had entailed over the last weeks, the bar owner came to our table and apologized that the tavern was out of beer. I don’t think that would ever happen back home in Canada, but I took it as a signal that it was time to leave and get them to their hotel.

The next morning I brought the guys to meet Steve and Ken in one of the small FBI Academy boardrooms on the second floor. They presented all the evidence gathered over the last twenty-nine days in the case and at the end of their presentation there was a good understanding of victimology, the abduction location and neighbourhood demographics. There had been no eyewitnesses. There was no physical evidence. But for the person who took Michael, there had been a high risk of being seen. With virtually no behavioural clues to interpret, there was little information for a crime-scene analysis. The likely personality descriptors of the unknown offender came from the FBI agent’s past investigative experiences and the research that Ken and others had conducted into these types of crimes more than anything else. The investigators were reminded that profilers dealt in probabilities, not possibilities. Anything was possible and investigators must keep their minds open to that.

The investigators had explored every lead and were frustrated by the lack of information to move their case forward. They asked the same questions as all dedicated investigators do. Have they missed something? Was there something more they could do? Their time spent in Quantico was also an opportunity for them to stop and take a breath. New eyes had taken a look at their case from a different perspective: eyes that didn’t have the media scrutinizing their every move; eyes that didn’t have to look at the anguished faces of family members. At the end of our meeting, I was confident that Steve and Ken had given them a better understanding of the most probable type of offender responsible for Michael’s disappearance. (As this investigation is still an open, confidential Victoria Police Department cold-case investigation, I can’t share any information regarding the details of the consultation, unknown offender profile or investigative suggestions that came out of the meeting.)

When the consultation was finished, lead investigator Detective John Smith thanked all of us for our time and signalled to his team to start packing their charts, reports, notes and photographs back into the banker’s boxes.

I saw in their faces and heard in their voices the toll this investigation was taking. Ken Lanning must have noticed it too. He interrupted their task. “Sit back down a minute, guys,” Ken said. “Just listen to one more thing I have to say.”

“There will come a time when this case will end for you,” Ken began. “All leads will have been followed up and in the end the person responsible for what happened to Michael Dunahee may never be found. Michael may never be found.” The room was silent.

“If that is what happens, you are still great police officers who did a great job. You are doing everything you can to solve this case. You will never let down the public, the Dunahee family or Michael. Remember that. Please.”

A few days later I went with the officers to the Washington studio filming of an

America’s Most Wanted

television episode featuring a segment on Michael Dunahee. The show’s host, John Walsh, was well known as a victims’ advocate since the murder of his own child, Adam, in 1981. The popular reality show first aired in 1988 and had helped to bring numerous missing children home. Detective Smith was featured on the syndicated show and dozens of tips were called in. The show rebroadcast parts of Michael’s story with updates on five separate occasions and later a $100,000 reward for information was offered but no tips received have resulted in any substantiated leads.