Cracked (24 page)

Authors: James Davies

To unravel this mystery, let's return to Watters in Hong Kong, who was now on the brink of finding an answer.

3

As Watters continued his conversations with eating disorders expert Dr. Sing Lee, a key piece in the jigsaw puzzle at last slotted into place. One day in Lee's office in downtown Hong Kong, Lee told Watters that he had become gripped by the work of the eminent medical historian Edward Shorter, who had written many articles on the history of anorexia. What Shorter pointed out in his writing was that rates of anorexia and the form anorexia took had never been stable in the general population. Its form and prevalence had fluctuated from period to period.

For example, in the mid-1800s anorexia did not actually exist as a distinct medical category. It was rather regarded as one of the symptoms of a broader condition, then called hysteria. This catchall term characterized a suite of symptoms, most usually afflicting middle- and upper-middle-class women, which included things like uncontrollable ticks, muscular paralysis, fainting fits, bouts of vomiting, and in many cases a complete refusal to eat food. But in 1873 an expert in hysteria, the French physician Ernest-Charles Lasègue, came to the conclusion that self-starving warranted its own official designation, as he theorized it was often a stand-alone condition.

At the time Lasègue coined the term anorexia for the first time, he also drew up a thorough description of its core symptoms and a template guiding physicians in their diagnosis and treatment of the condition. It was clear that Lasègue's work at last provided a model, as Shorter put it, “of how patients should behave and doctors should respond.”

186

The question now was whether Lasègue's work was related to a rise in the disease.

Even though there were no epidemiological studies of anorexia rates in Lasègue's day, what Shorter noticed was that anecdotal reports suggested that once anorexia became part of the medical canon, its diagnostic prevalence increased too. Whereas in the 1850s the disorder was still confined to just a few isolated cases, after Lasègue's work it wasn't long before the term anorexia became standard in the medical literature, and with this, the number of cases climbed. As one London doctor reported in 1888, anorexia behavior was now “a very common occurrence,” giving him “abundant opportunities of seeing and treating many cases”; and a medical student confidently wrote in his doctoral dissertation: “among hysterics, nothing is more common than anorexia.”

187

This rise in anorexia was fascinating to Shorter because it closely followed the trajectory of many other psychosomatic disorders he had studied during his historical investigations. These disorders were also not constant in form and frequency but came and went at different points in history. This led Shorter to theorize that many disorders that did not have known physical causes and did not behave like diseases such as cancer, heart disease, or Parkinson's, which seemed to express themselves in the same way across time and space. Rather, disorders like anorexiaâwith no known physical causeâseemed to be heavily influenced by historical and cultural factors. If a disorder gained cultural recognition, then rates of that disorder would increase.

This provided a challenge to the conventional explanation that a disorder could proliferate after being recognized by medicine, because doctors could now identify something previously off their radar. While it was no doubt true that once doctors knew what to look for diagnostic rates would inevitably increase, for Shorter it was essential to also consider the powerful role culture could play in the escalation of some disorders. In short, Shorter was convinced that medicine did not just “reveal” disorders that had previously escaped medical attention, but that one could actually increase their prevalence by simply putting the disorder on the cultural map.

To explain how this could happen, Shorter made use of an interesting metaphorâthat of the “symptom pool.” Each culture, he argued, possessed a metaphorical pool of culturally legitimate symptoms through which members of a given society would choose, mostly unconsciously, to express their distress. It was almost as if a particular symptom would not be expressed by a given cultural group until the symptom had been culturally recognized as a legitimate alternativeâthat is, until it had entered that culture's “symptom pool.” This idea could help explain, among other things, why symptoms that were very common in one culture would not be in another.

Why, for example, could men in Southeast Asia but not men in Wales or Alaska experience what's called

Koro

(the terrifying certainty that their genitals are retracting into their body)? Or why could menopausal women in Korea but not women in New Zealand or Scandinavia experience

Hwabyeong

(intense fits of sighing, a heavy feeling in the chest, blurred vision, and sleeplessness)? For Shorter, the answer was simple: symptom pools were fluid, changeable, and culturally specific, therefore differing from place to place.

This idea implied that certain disorders we take for granted are actually caused less by biological than cultural factorsâlike crazes or fads, they can grip or release a population as they enter or fade from popular awareness. This was not because people consciously chose to display symptoms that were fashionable members of the symptom pool, but just that people seem to gravitate unconsciously to expressing those symptoms high on the cultural scale of symptom possibilities. And this of course makes sense, as it is crucial that we express our discontent in ways that make sense to the people around us (otherwise we will end up not just ill but ostracized).

As Anne Harrington, professor of history of science at Harvard, puts it, “Our bodies are physiologically primed to be able to do this, and for good reason: if we couldn't, we would risk not being taken seriously or not being cared for. Human beings seem to be invested with a developed capacity to mold their bodily experiences to the norms of their cultures; they learn the scripts about what kinds of things should be happening to them as they fall ill and about the things they should do to feel better, and then they literally embody them.”

188

Contagions do not spread through conscious emulation, then, but because we are unconsciously configured to embody species of distress deemed legitimate by the communities in which we live.

One of the reasons people find this notion of unintentional embodiment difficult to accept is that such processes occur above our headsâimperceptibly, unconsciouslyâand so we often fail to spot them. But if you still doubt the power of unintentional embodiment, then just try the following experiment. Next time you are sitting in a public space where there are others sitting opposite you, start to yawn conspicuously every one or two minutes, and do this for about six minutes. All the while, keep observing the people in your vicinity. What you'll almost certainly notice is that others will soon start yawning too.

Now, there are many theories why this may happen (due to our “capacity to empathize,” or to an offshoot of the “imitative impulse”). But the actual truth is that no one really knows for sure why. All we do know is that those who have caught a yawning bug usually do not know they have been infected. They usually believe they are yawning because they are tired or bored, not because someone across the way has just performed an annoying yawning experiment.

Such unintentional forms of embodiment have been captured in many different theories developed by social psychologists. One theory of particular note is what has been termed the “bandwagon effect.” This term describes the well-documented phenomenon that conduct and beliefs spread among people just like fashions or opinions or infectious diseases do. The more people who begin to subscribe to an idea or behavior, the greater its gravitational pull, sucking yet more people in until a tipping point is reached and an outbreak occurs. When an idea takes hold of enough people, in other words, it spreads at an ever-increasing rate, even in cases when the idea or behavior is neither good nor true nor useful.

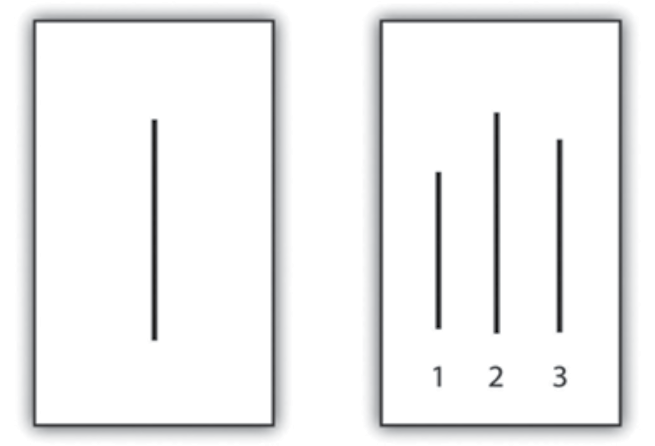

Take the following experiment as an example. Imagine that a psychologist gathers eight people around a table, but that only one of the eight people is not in on the experiment. That person is you. Everyone else knows precisely what is expected of them. What they have to do is give a prepared answer to a particular question. The question is: Which of the three lines in the box on the right most closely resembles the line on the left?

Easy, right? If you are sitting in a group where everyone is told to answer correctly, it is almost 100 percent certain that you will answer correctly too. But what would happen if you were put in a group where a sufficient number of members have been told to give an incorrect answer with sufficient forcefulness to many such slides? Unbelievable as it sounds, at least one-third of you will begin to give incorrect answers too. You will conclude, for instance, that the line in the box on the left resembles the line numbered 1 or 3 on the right.

Psychologist Solomon Asch demonstrated this bemusing occurrence by conducting this very experiment. His aim was to show that our tendency to conform to the group is so powerful that we often conform even when the group is wrong. When Asch interviewed the one-third of people who followed the incorrect majority view, many said they knew their answer was wrong but did not want to contradict the group for fear of being ridiculed. A few said that they really did believe the group's answers were correct. This meant that for some, the group's opinion had somehow unconsciously distorted their perceptions. What Asch's experiment revealed was that even when an answer is plainly obvious, we still have a tendency to be swayed in the wrong direction by the group. This is either because we do not want to stand alone, or because the bandwagon effect can so powerfully influence our unconscious minds that we will actually bend reality to fit in.

Because Asch showed it didn't take much to get us to conform to a highly implausible majority conclusion, the question is what happens when we are asked to conform to something discussed as real and true by powerful institutions like the media and psychiatry? The likelihood is that our rates of conformity will dramatically increase. And this is why the historian Edward Shorter believed that when it came to the spread of symptoms, the same “bandwagon effect” could be observed too

.

If enough people begin to talk about a symptom as though it exists, and if this symptom is given legitimacy by an accepted authority, then sure enough more and more people will begin to manifest that symptom.

This idea explained for Shorter why symptoms can dramatically come and go within a populationâwhy anorexia can reach epidemic proportions and then suddenly die away, or why self-harm can suddenly proliferate. As our symptom pool alters, we are given new ways to embody our distress, and as these catch on, they proliferate.

After reading Shorter's work, Dr. Lee began to understand what had happened in Hong Kong. Anorexia had escalated after Charlene's death because the ensuing publicity and medical recognition introduced into Hong Kong's symptom pool a hitherto foreign and unknown condition, allowing more and more women to unconsciously select the disorder as a way of expressing their distress.

This theory was also consistent with another strange change Dr. Lee had noticed

.

After

Charlene's death it wasn't just the rates of anorexia that increased but the actual form anorexia took. The few cases of self-starving Lee treated before Charlene's death weren't characterized by the classic symptoms of anorexia customarily found in the West, where sufferers believe they are grossly overweight and experience intense hunger when they don't eat. No, this particular set of Western symptoms did not match the experiences of anorexics that Lee encountered before the mid-1990s, where anorexics had no fear of being overweight, did not experience hunger, but were simply strongly repulsed by food.

This all changed as Western conceptions of anorexia flooded Hong Kong's symptom pool in the mid-1990s. Young women now began to conform to the list of anorexic symptoms drawn up in the West. Like Western anorexics, those in Hong Kong now felt grossly overweight and desperately hungry. In short, as part of the Western symptom drained eastward, the very characteristics of anorexia in Hong Kong altered too.

Watters now understood that Lee's discoveries in Hong Kong could be used to help partly explain a whole array of psychiatry contagions that could suddenly explode in any given population. The only problem was that Western researchers were loath to recognize how the alteration of symptom pools could account for these contagions. As he writes:

A recent study by several British researchers showed a remarkable parallel between the incidence of bulimia in Britain and Princess Diana's struggle with the condition. The incidence rate rose dramatically in 1992, when the rumors were first published, and then again in 1994, when the speculation became rampant. It rose to its peak in 1995, when she publically admitted the behavior. Reports of bulimia started to decline only after the princess's death in 1997. The authors consider several possible reasons for these changes. It is possible, they speculate, that Princess Diana's public struggle with an eating disorder made doctors and mental-health providers more aware of the condition and therefore more likely to ask about it or recognize it in their patients. They also suggest that public awareness might have made it more likely for a young woman to admit her eating behavior. Further, the apparent decline in 1997 might not indicate a true drop in the numbers but only that fewer people weren't admitting their condition. These are reasonable hypotheses and a likely explanation for part of the rise and fall in the numbers of bulimics. What is remarkable is that the authors of the study don't even mention, much less consider, the obvious fourth possibility: that the revelation that Princess Diana used bulimia as a “call for help”

encouraged

other young women to unconsciously mimic the behavior of this beloved celebrity to call attention to their own private distress. The fact that these researchers didn't address this possibility is emblematic of a pervasive and mistaken assumption in the mental health profession: that mental illnesses exist apart from and unaffected by professional and public beliefs and the cultural currents of the time.

189