Corporations Are Not People: Why They Have More Rights Than You Do and What You Can Do About It (15 page)

Authors: Jeffrey D. Clements,Bill Moyers

Self-serving? Ten of the for-profit health insurance corporations paid their CEOs a total of $1 billion in compensation between 2000 and 2009.

8

One “nonprofit” health insurance corporation, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Massachusetts, fired its CEO in 2011 with a $12 million severance and compensation package. CEOs of the ten largest publicly traded health insurance corporations earned a total of $118.6 million in 2007.

Meanwhile, back in the public sector, “the Administrator of the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, who manages the health care of forty-four million elderly Americans on Medicare and about fifty-nine million low-income and disabled recipients on Medicaid,” is paid $176,000.

9

It is hard to see how the Chamber serves the interests of America’s businesspeople and employees who pay towering health insurance premiums to help fund massive executive salaries and multimillion-dollar lobbying campaigns to block “government” health care.

In addition to protecting bloated health insurance companies, the Chamber works in other areas to protect the few and hurt the many. Bailed-out Wall Street corporations use the Chamber to

block financial reform. Subsidy-collecting fossil fuel corporations pay the Chamber to block energy reform. In fact, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce opposition to any effort to address the climate crisis is so extreme that even other global corporations such as Apple, Nike, and PG&E have resigned from the Chamber in protest.

10

What About Union Spending?

“What about unions?” Anyone who questions the impact of staggering amounts of corporate money in our democracy will hear that from time to time. The question makes sense: Americans distrust excessive concentrations of power and potential corruption, regardless of the institution in which the power is concentrated. We should seek transparency and accountability, checks and balances for any institution that has concentrated power, whether governmental, corporate, union, or otherwise. But we also should consider some facts about unions before accepting false equivalency with corporations.

The Chamber of Commerce says not to worry,

Citizens United

“provided unions with the same political speech rights as corporations.”

11

David Bossie, who brought the

Citizens United

case, says the “newfound freedom” for corporations makes a “level playing field” with unions and interest groups.

12

Perhaps they think that unions will somehow balance out corporate power.

Unfortunately, they won’t. First, the federal law that the

Citizens United

case struck down had assumed a level playing field; corporations

and

unions were covered by the same restrictions on election spending. That had been true since 1947. If you are concerned about union political spending, then

Citizens United

is a disaster for you, too, since

Citizens United

blocks Congress and the states from restricting union election spending. In that sense, David Bossie is correct:

Citizens United

means that democracy is for sale to any and all that have the cash to bid.

Behind this vision of a pay-to-play democracy is a deeply flawed premise that Americans are supposed to be spectators rather than governing citizens as corporations and unions throw money around to decide our elections. That assumption, however, is not the only thing wrong with the “level playing field” viewpoint about unions. In real life, there is no such thing as equality between unions and corporations, just as there is no equivalence between most people and the CEOs of large corporations.

First, a union is very different from a corporation. A union is an organization of employees. The employees agree to be represented by an elected leadership of the organization. The leadership negotiates with employers to reach terms of employment on behalf of all of the workers, terms that are approved by the workers, as well as by management of the business. People who decide to form unions may choose to incorporate the union, or they may not. Some unions are corporations, but many other unions are not. Unincorporated unions are simply voluntary associations of workers or federations of local “chapters.” The largest labor organizations, such as the AFL-CIO, are federations of smaller unions.

That does not make unions perfect, and it’s true that union corruption has been a problem at times, as in any human institution. When they worked well, though, as they usually did and continue to do, unions offer some counterbalance to corporate power. They provide an employee voice into the question of how corporate profits should be allocated among all of the people who contribute. In the long-gone heyday of unions, when corporations profited, everyone did well. Shareholders still gained, and CEOs and executives still made a fine living, but unions helped employees get a fair share, too.

Strong unions helped create the middle class. In the 1950s, when unions represented more than 35 percent of American workers in the private sector, wages rose. More people who

worked hard had a chance to have health insurance and to retire in something better than poverty. For a variety of reasons, though, including corporate union suppression tactics, the rate of union membership declined steeply. By 1970, only one in four private sector workers was in a union. This number kept falling until today, when unions represent only 7 percent of private sector employees.

13

That means that 93 percent of private sector employees are

not

in unions.

So one answer to the question “What about unions?” is “What unions? They don’t count anymore.” That’s not a complete answer, however. While private sector unions have declined significantly, public sector unions have grown over the same years. About 35 percent of public sector employees now belong to unions. Though the data are mixed, unions in the public sector have probably helped those employees retain slightly more of what all Americans seek—a decent wage, health care, some possibility of retirement, and some level of security.

Also, it’s true that public and private union members spend money to influence government and policy. Union members pool contributions through political action committees (PACs), and unions do have political influence, particularly in the Democratic Party. In 2010, members of SEIU (a union representing service employees) contributed over $11 million, members of teachers’ unions contributed $15 million, and the teamsters, electrical workers, and carpenters all contributed millions of dollars. So unions should not be exempt from any examination of the influence of money in politics.

Upon examination, however, the falsity of assertions about union-corporation parity is apparent. Unions do not have the membership, money, or influence to come anywhere close to balancing corporate power. The high ground for union members in politics comes at election time. Apart from the PAC spending

(which itself is dwarfed by corporate money), unions can mobilize members to help get out voters and rally for favored candidates. But then the election is over, and regardless of the winner, corporate influence in government overwhelms unions as much as it overwhelms every other interest.

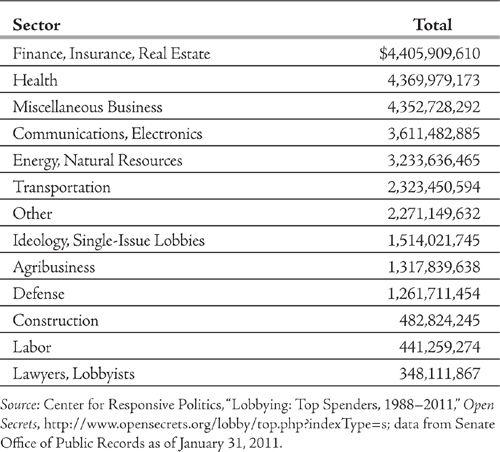

If you go back and look at that top-twenty list of lobbying spenders, you will see not a single union or federation of unions on the list. Not one. If we pull back from the top-twenty list to see

all

lobbying spending, including unions, corporate industries, and “special interests,” the corporate domination remains clear (see

Table 2

).

In summary, corporate spending on lobbying came to more than $20 billion; union spending on lobbying, $0.4 billion. The financial industry alone spent $4 billion more than all of the unions combined, in every field, in the public and private sectors. Even by Wall Street’s accounting, $20 billion and $0.4 billion are not close to equivalent.

Apart from the overwhelming magnitude of corporate money, the type of money from a union is different. Jon Youngdahl, national political director of the SEIU, explains where that $11 million that SEIU put into elections last year came from:

About 300,000 janitors, nurses’ aides, child-care providers and other members who voluntarily contribute on average $7 per month to SEIU’s Committee on Political Education (COPE)…. We are a union of working people, and the money we spend on politics is money donated by workers.

14

Finally, in lobbying spending as elsewhere, the outputs reflect the inputs. If unions are using whatever power they have to drive into our government the union agenda—enlarged union membership, better wages, health care and pensions for union members, and in the private sector, a more equitable division of corporate earnings among executives, shareholders, and employees—they have failed miserably. By contrast, transnational corporate spending to dominate government has been a very good investment for the largest corporations.

Table 2

Lobbying Expenditures by Industry (1998-2010)

What Corporations Get for the Money

Virtually every significant issue now reflects a corporate agenda, with the possible exception of social issues of limited economic impact, such as abortion, lesbian and gay rights, and the role of religion in public life. Consider two macro issues: spending versus debt; and energy and the environment. Whether Americans can find a way to manage these two issues wisely may have the most impact on whether we face precipitous decline as a nation and as

a world. On both, the well-financed corporate agenda overwhelms the public national interest.

Corporate Power Drives Deficits and Debt

Admiral Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has identified the growing national debt as one of the most significant national security issues.

15

The national debt, approximately $10 trillion, is now at the highest point, as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), since 1946, in the aftermath of the Great Depression and World War II.

16

If current Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections hold, that debt will rise to $16 trillion in ten years.

The biggest contributing factors to the rapid debt increase since 2001 are (1) trillions of dollars in “temporary” tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 that remain in place, (2) the costs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (the latter alone was costing $10 billion per month in 2011), (3) the enactment of a massive prescription drug benefit called Medicare Part D without funding the program, and (4) the collapse of the global financial system in 2008, followed quickly by the government bailouts to Wall Street and financial firms.

17

The national debt reflects accumulated borrowing over the years. The budget deficit, on the other hand, reflects the amount of government spending in excess of government revenue in any given year. Continued deficits contribute to rising national debt.

In 2010, by official measures, the $3.5 trillion federal budget broke down as follows: Medicaid and Medicare, 21 percent; military, 20 percent; Social Security, 20 percent; “mandatory” spending (veterans’ compensation, unemployment, food stamps, and so on), 17 percent; “discretionary” spending (law enforcement, roads, student aid, energy, and the like), 16 percent; and interest payments on the national debt, 6 percent.

18

More accurate measures that

include all government spending for military purposes, not merely that counted in the Pentagon’s budget, show federal spending on the military and war much closer to 50 percent of the budget.

19

On the revenue side, in 2010, tax revenues fell to the lowest level since 1950.

20

For 2011, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office has projected the budget deficit to be $1.4 trillion. The CBO projects cumulative deficits of $6.7 trillion between 2012 and 2021.

21

What does any of this have to do with corporations? The corporate stranglehold on Washington drives huge corporate subsidies and earmarks. Diverse organizations from Public Citizen to the Cato Institute calculate “corporate welfare,” defined as unnecessary federal spending and subsidies for specific corporations, at $92 billion to $125 billion per year.

22

The Cato Institute describes subsidies for corporate agribusiness ($26 billion in 2006, as much as $30 billion in 2010) as, “a long-standing rip-off of American taxpayers.”

23

The vast majority of agriculture subsidies do not go to “family farms” but to the biggest corporate producers. These subsidies could not be justified on any measure of public policy merit; they are bad for the health of the American people and an unfair business advantage for large corporations over small business. Taxpayer subsidies for corn production and industrialized by-products make unwholesome and fattening foods and drinks artificially cheap and place locally grown, organic, and otherwise healthy unprocessed food in an unfair competitive position.

Why does a practice that is bad for people and the country continue? Look back at

Table 2

; “agribusiness” is one of the largest lobbying machines in Washington, spending over $1.3 billion in the past decade.