Copenhagen (17 page)

Authors: Michael Frayn

*

I have had many helping hands with this play, both before it was produced in London and since. Sir John Maddox kindly read the text for me, and so did Professor Balázs L Gyorffy, Professor of Physics at Bristol University, who made a number of corrections and suggestions. I am also indebted to Finn Aaserud, the Director of the Niels Bohr Archive in Copenhagen, and to his colleagues there, for much help and encouragement. Many scientists and other specialists have written to me after seeing the play on the stage. They have mostly been extraordinarily generous and supportive, but some of them have put me right on details of the science, for which I am particularly grateful. They also pointed out two mathematical errors so egregious that the lines in question didn’t make sense from one end to the other—even to me, when I re-read them. All these points have now been addressed, though I’m sure that other mistakes will emerge. So much new material has come to hand, in one way or another, that I have extensively overhauled and extended this Postscript to coincide with the production of the play in New York.

One matter of dispute that I have not been able to resolve completely concerns the part played by Max Born in the introduction of quantum mechanics. The matter was raised (with exemplary temperance) by his son, Gustav Born, who was concerned about the injustice he felt I had done to his father’s memory. I was reluctant to make the play any more complex than it is, but I have since made adjustments both to the play itself and to this Postscript which go at any some way to meeting Professor Born’s case. We are still at odds over one line, though, in which Heisenberg is said to have’invented quantum mechanics’. I am quoting the judgment of other physicists here (including one not especially sympathetic to Heisenberg), but I realise that it is a huge over-simplification, and that it seems to compound the original injustice committed when Heisenberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1932 ‘for the creation of quantum mechanics’, while Born had to wait another 22 years to have his part acknowledged in the same way. The trouble is that I have not yet been able to think of another way of putting it briefly enough to work in spoken dialogue.

The American physicist Spencer Weart, in a letter to Finn Aaserud, very cogently pointed out that the calculation of the critical mass was much harder than I’ve made it seem for Heisenberg once Bohr has suggested it to him. ‘Perrin failed to get it and his publication of a ton-size critical mass subtly misled everyone else, then Bohr and Wheeler failed, Kurchatov failed, Chadwick failed, all the other Germans and Russians and French and British and Americans missed it, even the greatest of them all for such problems, Fermi, tried but missed, everyone except Peierls … Physics is hard.’

Some correspondents have also objected to Heisenberg’s line about the physicists who built the Allied bomb, ‘Did a single one of them stop to think, even for one brief moment, about what they were doing?’, on the grounds that it is unjust to Leo Szilard. It’s true that in March 1945 Szilard began a campaign to persuade the US Government not to use the bomb. A committee was set up—the Committee on Social and Political Implications—to allow the scientists working on the project to voice their feelings, and Szilard also circulated a petition among the scientists, 67 of whom signed it, which mentioned ‘moral considerations,’ though it did not specify what exactly these were.

But the main stated reasons for Szilard’s second thoughts were not to do with the effects that the bomb would have on the Japanese—he was worried about the ones it would have on the Allies. He thought (presciently) that the actual use of the bomb on Japan would precipitate an atomic arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Committee’s report (which Szilard himself seems to have written) and the petition stressed the same points. By this time, in any case, the bomb was almost ready. It had been Szilard who urged the nuclear programme in the first place, and at no point, so far as I know, while he worked for it (on plutonium production) did he ever suggest any hesitation about pursuing either the research or the actual manufacture of the bomb.

I think the line stands, in spite of Szilard’s afterthoughts. The scientists had already presented their government with the bomb, and it is the question of whether the German

scientists were ready or not to do likewise that is at issue in the play. If Heisenberg’s team

had

built a bomb, I don’t think they would have recovered very much moral credit by asking Hitler to be kind enough not to drop it on anyone—particularly if their objection had been the strain it might place upon post-war relations among the Axis powers.

*

One looming imponderable remains. If Heisenberg had made the calculation, and

if

the resulting reduction in the scale of the problem had somehow generated a real eagerness in both the Nazi authorities and the scientists, could the Germans have built a bomb? Frank believes that they could not have done it before the war in Europe was over—‘even the Americans, with substantial industrial and scientific advantage, and the important assistance from Britain and from ex-Germans in Britain did not achieve that (VE-Day, 8 May 1945, Trinity test, Alamogordo, 6 July 1945).’ Speer (who as armaments minister would presumably have had to carry the programme out) suggests in his memoirs that it might have been possible to do it by 1945, if the Germans had shelved all their other weapons projects, then two paragraphs later more cautiously changes his estimate to 1947; but of course he needs to justify his failure to pursue the possibility. Powers makes the point that, whatever the timetable was, its start date could have been much earlier. Atomic energy in Germany, he argues, attracted the interest of the authorities from the first day of the war. ‘The United States, beginning in June 1942, took just over three years to do the job, and the Soviet Union succeeeded in four. If a serious effort to develop a bomb had commenced in mid-1940, one might have been tested in 1943, well before the Allied bomber offensive had destroyed German industry.’

If this ‘serious effort’ had begun only after Heisenberg’s visit to Copenhagen, as the play suggests might have happened if the conversation with Bohr had gone differently, then even this timetable wouldn’t have produced a bomb until late 1944—and by that time it was of course much less

likely that German industry could have delivered. In any case, formidable difficulties remained to be overcome. The German team were hugely frustrated by their inability to find a successful technique for isolating U235 in any appreciable quantity, even though the experimental method, using Clusius-Dickel tubes, was of German origin. They could have tried one of the processes used sucessfully by the Allies, gaseous diffusion. This was another German invention, developed in Berlin by Gustav Hertz, but Hertz had lost his job because his uncle was Jewish. (It was, incidentally, the delays in getting the various American isotope-separation plants to function which meant that the Allied bomb was not ready in time for use against Germany.)

The failure to separate U235 also held up the reactor programme, and therefore the prospect of producing plutonium, because they could not separate enough of it even for the purposes of enrichment (increasing the U235 content of natural uranium), so that it was harder to get the reactor to go critical. The construction of the reactor was further delayed because Walther Bothe’s team at Heidelberg estimated the neutron absorption rates of graphite wrongly, which obliged the designers to use heavy water as a moderator instead. The only source of heavy water was a plant in Norway, which was forced to close after a series of attacks by Norwegian parachutists attached to Special Operations Executive, American bombers, and the Norwegian Resistance. Though perhaps, if a crash programme had been instituted from the first day of the war, enough heavy water might have been accumulated before the attacks were mounted.

If, if, if .… The line of ifs is a long one. It remains just possible, though. The effects of real enthusiasm and real determination are incalculable. In the realm of the just possible they are sometimes decisive.

*

Anyone interested enough in any of these questions to want to sidestep the fiction and look at the historical record should certainly begin with:

Thomas Powers:

Heisenberg’s War

(Knopf 1993; Cape 1993)

David Cassidy:

Uncertainty: The Life and Science of Werner Heisenberg

(W H Freeman 1992)

Abraham Pais: Niels

Bohr’s Times

(OUP 1991)—Pais is a fellow nuclear physicist, who knew Bohr personally, and this, in its highly eccentric way, is a classic of biography, even though Pais has not much more sense of narrative than I have of physics, and the book is organised more like a scientific report than the story of someone’s life. But then Bohr notoriously had no sense of narrative, either. One of the tasks his assistants had was to take him to the cinema and to explain the plot to him afterwards.

Werner Heisenberg:

Physics and Beyond

(Harper & Row 1971)—In German,

Der Teil und das Ganze

. His memoirs.

Jeremy Bernstein:

Hitler’s Uranium Club, the Secret Recordings at Farm Hall

, introduced by David Cassidy (American Institute of Physics, Woodbury, New York 1996)

or the British edition of the transcripts:

Operation Epsilon, the Farm Hall Transcripts

, introduced by Sir Charles Frank. (Institute of Physics Publishing 1993)

Also relevant:

Heisenberg:

Physics and Philosophy

. (Penguin 1958)

Niels Bohr:

The Philosophical Writings of Niels Bohr

(Oxbow Press, Connecticut 1987)

Elizabeth Heisenberg:

Inner Exile

(Birkhauser 1984)—In German

Das politische Leben eines Unpolitischen

. Defensive in tone, but revealing about the kind of anguish her husband tended to conceal from the world; and the source for Heisenberg’s ride home in 1945.

David Irving:

The German Atomic Bomb

(Simon & Schuster 1968)—in UK as

The Virus House

(Collins 1967). The story of the German bomb programme.

Paul Lawrence Rose:

Heisenberg and the Nazi Atomic Bomb Project

(U of California Press 1998)

Records and Documents Relating to the Third Reich, II German Atomic Research, Microfilms DJ29-32

. (EP Microform Ltd, Wakefield) living’s research materials for the book, including long verbatim interviews with Heisenberg and others. The only consultable copy I could track down was in the library of the Ministry of Defence.

Archive for the History of Quantum Physics

, microfilm. Includes the complete correspondence of Heisenberg and Bohr. A copy is available for reference in the Science Museum Library. Bohr’s side of the correspondence is almost entirely in Danish, Heisenberg’s in German apart from one letter.

Leni Yahil:

The Rescue of Danish Jewry

, (Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia 1969)

There are also many interesting sidelights on life at the Bohr Institute in its golden years in:

French & Kennedy, eds:

Niels Bohr, A Centenary Volume

(Harvard 1985)

and in the memoirs of Hendrik Casimir, George Gamow, Otto Frisch, Otto Hahn, Rudolf Peierls, and Victor Weisskopf.

For the subsequent challenges to the Copenhagen Intepretation:

David Deutsch:

The Fabric of Reality

(Allen Lane 1997)

Murray Gell-Mann:

The Quark and the Jaguar

(W H Freeman 1994; Little, Brown 1994)

Roger Penrose:

The Emperor’s New Mind

(OUP 1989)

The actual ‘two-slits’ experiment was carried out by Dürr, Nonn, and Rempe at the University of Konstanz, and is reported in

Nature

(3 September 1998). There is an accessible introduction to the work in the same issue by Peter Knight, and another account of it by Mark Buchanan (boldly entitled ‘An end to uncertainty’) in

New Scientist

(6 March 1999).

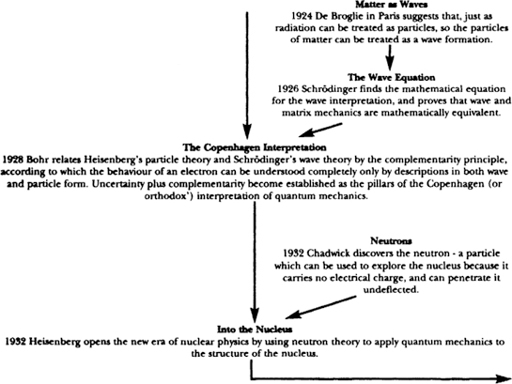

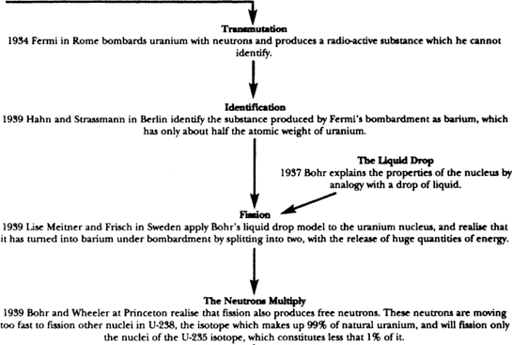

Overleaf: a diagram outlining

Copenhagen

’s scientific and historical background.

From the beginning of modern atomic theory to Hiroshima: an outline sketch of the scientific and historical background to the play

.