Congo (76 page)

Authors: David Van Reybrouck

During his first year in office, Kabila seemed to be aiming for a strong, authoritarian, and extremely personalized state, but in practice that state remained quite feeble. There was no real policy, no vision, no government apparatus. Even the army was a joke. Mobutu’s Forces Armées Zaïroises (FAZ) was disbanded and replaced by the Forces Armées Congolaises (FAC). It sounded official, but was in fact a hodgepodge of former FAZ soldiers, former Katangan Tigers,

kadogos

, Banyamulenge, and Rwandan Tutsis. The chief of staff was the Rwandan James Kabarebe. Kabila oversaw his country the way he had once overseen his rebel territory: laxly, very laxly. The only thing about which he was conscientious was maintaining control over the channels of information. It was no mistake, therefore, that his adviser for all things communications-related was once again Dominique Sakombi Inongo, the propagandist-turned-prophet. Kabila must have learned that from Mobutu: a strong regime needs to keep the media in an iron grip. The radio journalist Zizi Kabongo found out about that himself one night at 2

A.M.

, when the army came pounding on his door.

“Kabila had a very cool relationship with the public broadcasting organization,” Kabongo told me.

He saw the entire staff as a clutch of Mobutists. One evening we rebroadcast one of his meetings. Kabila didn’t sleep much and he heard the broadcast. Ever since Mobutu we’d had no money for equipment, so we always had to erase our tapes and use them over again. But this one tape was badly erased. After the recording of Kabila’s meeting, there was a section of tape that still contained the tail end of a report on Mobutu. The technician on duty fell asleep, but at the end the listeners heard

papa Maréchal

’s voice again. “

Oyé! Oyé! Papa ndeko. Our friend!”

you heard the people shouting. Mobutu has returned, the listeners thought. That same night the army rounded up all the journalists to throw them into prison. They knocked on my door at two o’clock. In the prison, I ended up among men who had been sentenced to death and revolutionaries. The situation was quite grim. Kabila was out to eliminate all his enemies.

Zizi, whose shins bore the scars of resistance to Mobutu, stood accused of Mobutism. More than 160 journalists were imprisoned between May 1997 and January 2001.

8

“The next day we were all brought to the presidential palace. Kabila himself gave us a terrible scolding for our act of rebellion. For punishment, we were all obliged to study Marxism. But when it was over we finally got the new tapes we’d been waiting for for years.”

9

The democratic opposition and the UDPS had been stiff-armed, the AFDL resigned to the scrapheap, the press snarled at and then silenced. What other bridges were left for the new leader to blow up? Those connecting the country to its foreign allies, of course. Within no time Kabila blew his credit with the United Nations by first refusing, then obstructing, an investigation of the mass extermination of Hutu refugees. Foreign teams of experts were systematically boycotted. Kabila was faced with a choice: he could either place the blame on Rwanda (which was where it belonged) and thereby admit that his victory was not due to his own rebellion, an admission that would destroy his popularity at home, or he could take the blame himself, which would earn him an international reputation as a brutal mass murderer. Domestic interest and international interests were at a standoff. It would have been a high-wire act even for a seasoned politician, and Kabila was no seasoned politician. Diplomacy was mumbo jumbo to him; boorishness was his strong suit. He entered the international arena like a suspicious rebel rather than a senior statesman. Within no time he had accused France of neocolonialism and America of a lack of diplomatic courtesy, and had called Belgium a terrorist state.

10

All three of those countries had put up with a great deal from Mobutu in his day, but ludicrous statements like this were something new. This was no longer the voice of a sly fox, but of a clodhopper. Other African heads of state, too, soon became familiar with their new colleague. In 1997 Nelson Mandela waited for him for hours at the peace talks in Congo-Brazzaville; the affront threw the always-genteel statesman into a rare paroxysm of rage. Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak was already waiting for him at the airport in Cairo, with an honor guard and the red carpet, when Kabila called to cancel the appointment because he felt “a bit tired.” Tanzanian president Benjamin Mkapa actually welcomed him to his residence, but in complete defiance of diplomatic protocol Kabila cut the visit short and flew back to Kinshasa.

11

President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda and Vice President Paul Kagame of Rwanda would also become acquainted with their protégé’s unmannered ways. They had hoped to control their chaotic neighbor by installing a pawn of their own, but Kabila turned out to be an unguided missile.

And then something very important happened: Kabila turned his back on Rwanda and Uganda. He had little choice in the matter. All over the country there was growing protest against the foreign interference. Rwanda in particular became the whipping boy. Every Tutsi was seen as Rwandan and every Rwandan as an occupier. Things even reached a point where anyone with a pointed nose or high forehead was seen almost immediately as an infiltrator. People in Kinshasa were extremely annoyed by the highly visible presence of Tutsis in the armed forces, often in high-ranking positions. These were officers who spoke neither French nor Lingala, but English, Swahili, and Kinyarwanda. These new military leaders frequently behaved like arrogant victors and saw no problem in reinstating the

chicotte

, the strop of hippopotamus hide that summoned up so many bad memories of colonial days. Women who wore jeans or a miniskirt in public, which had been allowed since 1990, received a public lashing. Taxi drivers committing a traffic violation did too. The number of lashes was not limited to twenty-five, as officially established in colonial times, but was determined by age: a fifty-year-old received fifty lashes. It became a widely accepted idea that overpopulated Rwanda was longing for raw materials and lebensraum, and therefore had its eye on Kivu, where so many Tutsis already lived. People believed that Rwanda was out to establish a Grande République des Volcans (great volcanic republic), a new state consisting of Rwanda and Kivu. It did not help any when a group of prominent Rwandans publicly called for a “second Berlin Conference” to reconsider the borders established in 1885.

12

Some Congolese felt that their huge country had already been annexed by the dwarf state of Rwanda.

13

A deep, deep hatred arose between the two countries, reminiscent of the relations in more distant times between China and Japan or Ireland and England. Many Rwandans considered Congo to be a country of lazy, chaotic bunglers who cared more about music, dancing, and food than about work, infrastructure, and public order. Many Congolese saw Rwanda as a cold, authoritarian country where plastic bags were banned for reasons of public cleanliness and motorcycle helmets were mandatory, a country of arrogant, pretentious parvenus who looked down on them in contempt. Many interpreted the differences between the countries in terms of an ancient cultural conflict between “Bantus” and “Nilotes,” even though those were highly problematic concepts from colonial anthropology. As long as Kabila’s court was filled with those hateful foreigners, he could forget about his authority being recognized: the president knew that was how the people felt. So there he was at the head of a vast country, in a city that was new to him, with a population he neither knew nor understood. Little by little, the cheers died out. “We need to give our liberators back their liberty,” people on the street said scornfully.

14

And that was precisely what Kabila did. In a nighttime broadcast on July 26, 1998, more than a year after his glorious entry into Kinshasa, he announced that Rwandan and other foreign soldiers were to leave the national territory. This time it was not a matter of a badly erased tape. The Congolese people were thanked “for tolerating and giving shelter to the Rwandan troops.”

15

That communiqué sealed for good the break with Kigali and Kampala. In the days that followed, hundreds of soldiers left Kinshasa. Chief of staff James Kabarebe, the man who had taken Congo in Kabila’s name, was thanked for services rendered. He returned to Rwanda in a fury. A new escalation was now inevitable. And indeed, less than one week later he invaded Congo again.

T

HE WAR THAT LASTED FROM

O

CTOBER

1996

TO

M

AY

1997 and brought about Mobutu’s fall is known by many names: the Banyamulenge uprising, the war of liberation, the AFDL offensive. These days it is more commonly referred to as the First Congo War. On August 2, 1998, the Second Congo War broke out. Rwandan troops crossed the border again, Kabarebe again led the invasion, the objective was once again regime change in Kinshasa. This time, however, conflict would not last seven months but five years, until June 2003. Officially, that is, for unofficially the war simmered on, at least until the moment that I write this, in spring 2010.

The Second Congo War was an extremely complex conflict in which, at a certain point, no fewer than nine African countries and some thirty local militias took part. It was a showdown on an African scale, with Congo as the central theater of war. The promptness with which a number of states, from Namibia in the south to Libya in the north, chose sides (for or against Kabila) was reminiscent of the formation of the ententes in Europe on the eve of World War I. Because of its continental scope, it is sometimes referred to as the First African World War, but that is an unfortunate term that skims too lightly over the ponderous impact that the World Wars I and II had on Africa. The term

Great African War

is therefore more useful, even though the hotbed of the conflict was limited mostly to Congo, and the local militias were active for a longer period than any foreign national troops. In terms of casualties, this Great African War or Second Congo War developed into the deadliest conflict since World War II. Since 1998 at least three million and perhaps as many as five million people have been killed in hostilities in Congo alone, more than in the media-saturated conflicts in Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan put together. And their numbers continue to rise. In 2007, an estimated forty-five thousand casualties were still being reported as a result of the indirect consequences of that forgotten war. Most of those were civilians. They did not die in the course of fighting, but as a result of malnutrition, dysentery, malaria, and pneumonia: afflictions that could not be treated because of the war. One must note, however, that many of those maladies were not being treated before the war either. Congo already had an above-average mortality rate and the conflict did nothing to ameliorate that. In 2007 that rate was still 60 percent higher than in all the rest of sub-Saharan Africa.

16

Average Congolese life expectancy at birth was fifty-three.

The Second Congo War disappeared from the international media reports because it was considered incomprehensible and obscure. And indeed, there were no two clearly delineated camps; even more, there was no clear division of roles into villain and underdog. After the Cold War, Western journalists increasingly came to apply a moral frame of reference in reporting on armed conflicts: in Yugoslavia, the Serbs were the major culprits; in Rwanda, the Tutsis were the innocent victims. In both cases that led to disastrous misrepresentations and policy measures. In Congo it was not particularly easy to find a “good” side. Anyone viewing the conflict from close up knew that all those involved had their own skeletons in the closet. The grievances often seemed justified and the methods chosen often problematic. None of the parties seemed able to step back from the fray, either literally or figuratively, in order to consider the legitimacy of the other’s perspective and search for common ground. For a grindingly poor country with a young, uneducated population that had known only Mobutu’s dark despotism, that was definitely too much to ask. The children of a dictatorship are rarely model democrats. The Second Congo War became a conflict in which everyone found everyone else just a shade more culpable, so that hitting back was allowable and an endless spiral of violence could ensue. The Western media turned and left.

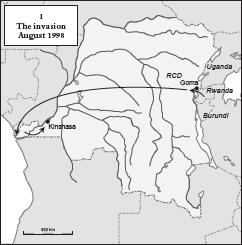

MAP 9: THE SECOND CONGO WAR

Rwanda, backed by Uganda and Burundi, invades Congo. The cities in the east are taken immediately, an air link to the far west of the country is intended to hasten the taking of Kinshasa. The invasion is made out to be the work of a domestic rebel movement: the RCD.