Complete Works of Wilkie Collins (1708 page)

Read Complete Works of Wilkie Collins Online

Authors: Wilkie Collins

The only immediate objection to this ingenious proposition was started by the doctor, who sarcastically inquired of Simon, “what he thought Mrs. Heavysides would say to it?” The carpenter confessed that this consideration had escaped him, and that Mrs. Heavysides was only too likely to be an irremovable obstacle in the way of the proposed arrangement. The witnesses all thought so too; and Heavysides and his idea were dismissed together after Simon had first gratefully expressed his entire readiness to leave it all to the captain.

“Very well, gentlemen,” said Captain Gillop. “As commander on board, I reckon next after the husbands in the matter of responsibility. I have considered this difficulty in all its bearings, and I’m prepared to deal with it. The Voice of Nature (which you proposed, Mr. Purling) has been found to fail. The tossing up for it (which you proposed, Mr. Sims) doesn’t square altogether with my notions of what’s right in a very serious business. No, sir! I’ve got my own plan; and I’m now about to try it. Follow me below, gentlemen, to the steward’s pantry.”

The witnesses looked round on one another in the profoundest astonishment — and followed.

“Pickerel,” said the captain, addressing the steward, “bring out the scales.”

The scales were of the ordinary kitchen sort, with a tin tray on one side to hold the commodity to be weighed, and a stout iron slab on the other to support the weights. Pickerel placed these scales upon a neat little pantry table, fitted on the ball-and-socket principle, so as to save the breaking of crockery by swinging with the motion of the ship.

“Put a clean duster in the tray,” said the captain. “Doctor,” he continued, when this had been done, “shut the doors of the sleeping-berths (for fear of the women hearing anything), and oblige me by bringing those two babies in here.”

“Oh, sir!” exclaimed Mrs. Drabble, who had been peeping guiltily into the pantry — ”oh, don’t hurt the little dears! If anybody suffers, let it be me!”

“Hold your tongue, if you please, ma’am,” said the captain. “And keep the secret of these proceedings, if you wish to keep your place. If the ladies ask for their children, say they will have them in ten minutes’ time.”

The doctor came in, and set down the clothes-basket cradle on the pantry floor. Captain Gillop immediately put on his spectacles, and closely examined the two unconscious innocents who lay beneath him.

“Six of one and half a dozen of the other,” said the captain. “I don’t see any difference between them. Wait a bit, though! Yes, I do. One’s a bald baby. Very good. We’ll begin with that one. Doctor, strip the bald baby, and put him in the scales.”

The bald baby protested — in his own language — but in vain. In two minutes he was flat on his back in the tin tray, with the clean duster under him to take the chill off.

“Weigh him accurately, Pickerel,” continued the captain. “Weigh him, if necessary, to an eighth of an ounce. Gentlemen! watch this proceeding closely; it’s a very important one.”

While the steward was weighing and the witnesses were watching, Captain Gillop asked his first mate for the log-book of the ship, and for pen and ink.

“How much, Pickerel?” asked the captain, opening the book.

“Seven pounds one ounce and a quarter,” answered the steward.

“Right, gentlemen?” pursued the captain.

“Quite right,” said the witnesses.

“Bald child — distinguished as Number One — weight, seven pounds one ounce and a quarter (avoirdupois),” repeated the captain, writing down the entry in the log-book. “Very good. We’ll put the bald baby back now, doctor, and try the hairy one next.”

The hairy one protested — also in his own language — and also in vain.

“How much, Pickerel?” asked the captain.

“Six pounds fourteen ounces and three-quarters,” replied the steward.

“Right, gentlemen?” inquired the captain.

“Quite right,” answered the witnesses.

“Hairy child — distinguished as Number Two — weight, six pounds fourteen ounces and three-quarters (avoirdupois),” repeated and wrote the captain. “Much obliged to you, Jolly — that will do. When you have got the other baby back in the cradle, tell Mrs. Drabble neither of them must be taken out of it till further orders; and then be so good as to join me and these gentlemen on deck. If anything of a discussion rises up among us, we won’t run the risk of being heard in the sleeping-berths.” With these words Captain Gillop led the way on deck, and the first mate followed with the log-book and the pen and ink.

“Now, gentlemen,” began the captain, when the doctor had joined the assembly, “my first mate will open these proceedings by reading from the log a statement which I have written myself, respecting this business, from beginning to end. If you find it all equally correct with the statement of what the two children weigh, I’ll trouble you to sign it, in your quality of witnesses, on the spot.”

The first mate read the narrative, and the witnesses signed it, as perfectly correct. Captain Gillop then cleared his throat, and addressed his expectant audience in these words:

“You’ll all agree with me, gentlemen, that justice is justice, and that like must to like. Here’s my ship of five hundred tons, fitted with her spars accordingly. Say she’s a schooner of a hundred and fifty tons, the veriest landsman among you, in that case, wouldn’t put such masts as these into her. Say, on the other hand, she’s an Indiaman of a thousand tons, would our spars (excellent good sticks as they are, gentlemen) be suitable for a vessel of that capacity? Certainly not. A schooner’s spars to a schooner, and a ship’s spars to a ship, in fit and fair proportion.”

Here the captain paused, to let the opening of his speech sink well into the minds of the audience. The audience encouraged him with the parliamentary cry of “Hear! hear!” The captain went on:

“In the serious difficulty which now besets us, gentlemen, I take my stand on the principle which I have just stated to you. My decision is as follows Let us give the heaviest of the two babies to the heaviest of the two women; and let the lightest then fall, as a matter of course, to the other. In a week’s time, if this weather holds, we shall all (please God) be in port; and if there’s a better way out of this mess than

my

way, the parsons and lawyers ashore may find it, and welcome.”

With those words the captain closed his oration; and the assembled council immediately sanctioned the proposal submitted to them with all the unanimity of men who had no idea of their own to set up in opposition.

Mr. Jolly was next requested (as the only available authority) to settle the question of weight between Mrs. Smallchild and Mrs. Heavysides, and decided it, without a moment’s hesitation, in favor of the carpenter’s wife, on the indisputable ground that she was the tallest and stoutest woman of the two. Thereupon the bald baby, “distinguished as Number One,” was taken into Mrs. Heavysides’ cabin; and the hairy baby, “distinguished as Number Two,” was accorded to Mrs. Smallchild; the Voice of Nature, neither in the one case nor in the other, raising the slightest objection to the captain’s principle of distribution. Before seven o’clock Mr. Jolly reported that the mothers and sons, larboard and starboard, were as happy and comfortable as any four people on board ship could possibly wish to be; and the captain thereupon dismissed the council with these parting remarks:

“We’ll get the studding-sails on the ship now, gentlemen, and make the best of our way to port. Breakfast, Pickerel, in half an hour, and plenty of it! I doubt if that unfortunate Mrs. Drabble has heard the last of this business yet. We must all lend a hand, gentlemen, and pull her through if we can. In other respects the job’s over, so far as we are concerned; and the parsons and lawyers must settle it ashore.”

The parsons and the lawyers did nothing of the sort, for the plain reason that nothing was to be done. In ten days the ship was in port, and the news was broken to the two mothers. Each one of the two adored her baby, after ten day’s experience of it — and each one of the two was in Mrs. Drabble’s condition of not knowing which was which.

Every test was tried. First, the test by the doctor, who only repeated what he had told the captain. Secondly, the test by personal resemblance; which failed in consequence of the light hair, blue eyes, and Roman noses shared in common by the fathers, and the light hair, blue eyes, and no noses worth mentioning shared in common by the children. Thirdly, the test of Mrs. Drabble, which began and ended in fierce talking on one side and floods of tears on the other. Fourthly, the test by legal decision, which broke down through the total absence of any instructions for the law to act on. Fifthly, and lastly, the test by appeal to the husbands, which fell to the ground in consequence of the husbands knowing nothing about the matter in hand. The captain’s barbarous test by weight remained the test still — and here am I, a man of the lower order, without a penny to bless myself with, in consequence.

Yes! I was the bald baby of that memorable period. My excess in weight settled my destiny in life. The fathers and mothers on either side kept the babies according to the captain’s principle of distribution, in despair of knowing what else to do. Mr. Smallchild, who was sharp enough when not seasick, made his fortune. Simon Heavysides persisted in increasing his family, and died in the work-house.

Judge for yourself (as Mr. Jolly might say) how the two boys born at sea fared in afterlife. I, the bald baby, have seen nothing of the hairy baby for years past. He may be short, like Mr. Smallchild — but I happen to know that he is wonderfully like Heavysides, deceased, in the face. I may be tall, like the carpenter — but I have the Smallchild eyes, hair, and expression, notwithstanding. Make what you can of that! You will find it come, in the end, to the same thing. Smallchild, junior, prospers in the world, because he weighed six pounds, fourteen ounces and three-quarters. Heavysides, junior, fails in the world, because he weighed seven pounds one ounce and a quarter. Such is destiny, and such is life. I’ll never forgive

my

destiny as long as I live. There is my grievance. I wish you good-morning.

This is a collection of three short stories, published in 1874.

The first two stories were used by Collins for readings in America; the third was written during his tour.

On his return to England, Collins further adapted them for book publication.

The dedication is to Oliver Wendell Holmes whom he met in Boston.

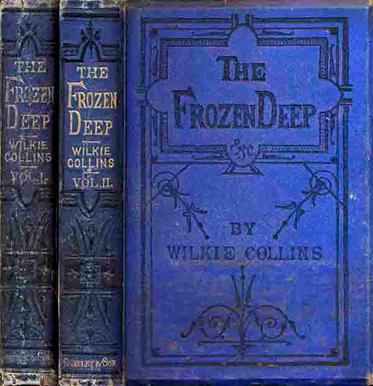

The Frozen Deep

is derived from the 1856 stage play.

The Dream Woman

is based on the 1855 short story republished in

The Queen of Hearts

(1859) with the principal characters renamed Francis Raven and Alicia Warlock.