Read Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) Online

Authors: JOSEPH CONRAD

Complete Works of Joseph Conrad (Illustrated) (238 page)

The sleeping judge woke up suddenly and snarled, “Why in Heaven’s name don’t we get on? We shall be all night. Let him call the second name on the list. We can take the Spanish ambassador when you have settled. For my part I think we ought to hear him....”

Lord Stowell said suddenly, “Prisoner at the bar, some gentlemen have volunteered statements on your behalf. If you wish it, they can be called.”

I didn’t answer; I did not understand; I wanted to tell him I did not care, because the Lion was posted as overdue and Seraphina was drowned. The Court seemed to be moving slowly up and down in front of me like the deck of a ship. I thought I was bound again, and on the sofa in the gorgeous cabin of the Madre-de-Dios. Someone seemed to be calling, “Prisoner at the bar... Prisoner at the bar....” It was as if the candles had been lit in front of the Madonna with the pink child, only she had a gilt anchor instead of the spiky gilt glory above her head. Somebody was saying, “Hello there.... Hold up!... Here, bring a chair,...” and there were arms around me. Afterwards I sat down. A very old judge’s voice said something rather kindly, I thought. I knew it was the very old judge, because he was called the star of Cuban law. Someone would be bending over me soon, with a lanthorn, and I should be wiping the flour out of my eyes and blinking at the red velvet and gilding of the cabin ceiling. In a minute Carlos and Castro would come... or was it O’Brien who would come? No, O’Brien was dead; stabbed, with a knife in his neck; the blood was still sticky between my first and second fingers. I could feel it. I ought to have been allowed to wash my hands before I was tried; or was it before I spoke to the admiral? One would not speak to a man with hands like that.

A loud, high-pitched voice called from up in the air, “I will give any of you gentlemen of the robe down there fifty pounds to conduct the remainder of the case for him. I am the prisoner’s father.”

My father’s voice broke the spell. I was in the court; the candles were still burning; all the faces, lit up or in the shadow, were bunched together in little groups; hands waved. The barrister whose face was like the devil’s under his wig held in his hands the paper that had been handed to Lord Stowell; my father was talking to him from the bench. The barrister, tall, his robes old and ragged, silhouetted against the light, glanced down the paper, fluttered it in his hand, nodded to my father, and began a grotesque, nasal drawl:

“M’luds, I will conduct the case for the prisoner, if your lordships will bear with me a little. He obviously can’t call his own witnesses. If he has been treated as he says, it has been one of the most abominable...”

Old Lord Stowell said, “Ch’t, ch’t, Mr. Walker; you know you must not make a speech for the prisoner. Call your witness. It is all that is needed.”

I wondered what he meant by that. The barrister was calling a man of the name of Williams. I seemed to know the name. I seemed to know the man, too.

“Owen Williams, Master of the ship Lion.... Coffee and dye-wood.... Just come in under a jury-rig. Had been dismasted and afterwards becalmed. Heard of this trial from the pilot in Graves-end. Had taken post-chaises...”

I only heard snatches of his answers.

“On the twenty-fifth of August last I was close in with the Cuban coast.... The mate, Sebright, got boiling water for them.... Afterwards a heavy fog. They boarded us in many boats....” He was giving all the old evidence over again, fastening another stone around my neck. But suddenly he said: “This gentleman came alongside in a leaky dinghy. A dead shot. He saved all our lives.”

His bullet-head, the stare of his round blue eyes seemed to draw me out of a delirium. I called out:

“Williams, for God’s sake, Williams, where is Seraphina? Did she come with you?” There was an immense roaring in my head, and the ushers were shouting, “Silence! Silence!” I called out again.

Williams was smiling idiotically; then he shook his head and put his finger to his mouth to warn me to keep silence. I only noted the shake of the head. Sera-phina had not come. The Havana people must have taken her. It was all over with me. The roaring noise made me think that I was on a beach by the sea, with the smugglers, perhaps, at night down in Kent. The silence that fell upon the court was like the silence of a grave. Then someone began to speak in measured, portentous Spanish, that seemed a memory of the past.

“I, the ambassador of his Catholic Majesty, being here upon my honour and on my oath, demand the re-surrender of this gentleman, whose courage equals his innocence. Documents which have just reached my hands establish clearly the mistake of which he is the victim. The functionary who is called Alcayde of the carcel at Havana confused the men. Nikola el Escoces escaped, having murdered the judge whose place it was to identify. I demand that the prisoner be set at liberty...”

A long time after a harsh voice said:

“Your Excellency, we retire, of course, from the prosecution.”

A different one directed:

“Gentlemen of the jury, you will return a verdict of ‘Not Guilty’...”

Down below they were cheering uproariously because my life was saved. But it was I that had to face my saved life. I sat there, my head bowed into my hands. The old judge was speaking to me in a tone of lofty compassion:

“You have suffered much, as it seems, but suffering is the lot of us men. Rejoice now that your character is cleared; that here in this public place you have received the verdict of your countrymen that restores you to the liberties of our country and the affection of your kindred. I rejoice with you who am a very old man, at the end of my life....”

It was rather tremendous, his deep voice, his weighted words. Suffering is the lot of us men!... The formidable legal array, the great powers of a nation, had stood up to teach me that, and they had taught me that — suffering is the lot of us men!

It takes long enough to realize that someone is dead at a distance. I had done that. But how long, how long it needs to know that the life of your heart has come back from the dead. For years afterwards I could not bear to have her out of my sight.

Of our first meeting in London all I remember is a speechlessness that was like the awed hesitation of our overtried souls before the greatness of a change from the verge of despair to the opening of a supreme joy.

The whole world, the whole of life, with her return, had changed all around me; it enveloped me, it enfolded me so lightly as not to be felt, so suddenly as not to be believed in, so completely that that whole meeting was an embrace, so softly that at last it lapsed into a sense of rest that was like the fall of a beneficent and welcome death.

For suffering is the lot of man, but not inevitable failure or worthless despair which is without end — suffering, the mark of manhood, which bears within its pain a hope of felicity like a jewel set in iron....

Her first words were:

“You broke our compact. You went away from me whilst I was sleeping.” Only the deepness of her reproach revealed the depth of her love, and the suffering she too had endured to reach a union that was to be without end — and to forgive.

And, looking back, we see Romance — that subtle thing that is mirage — that is life. It is the goodness of the years we have lived through, of the old time when we did this or that, when we dwelt here or there. Looking back, it seems a wonderful enough thing that I who am this, and she who is that, commencing so far away a life that, after such sufferings borne together and apart, ended so tranquilly there in a world so stable — that she and I should have passed through so much, good chance and evil chance, sad hours and joyful, all lived down and swept away into the little heap of dust that is life. That, too, is Romance!

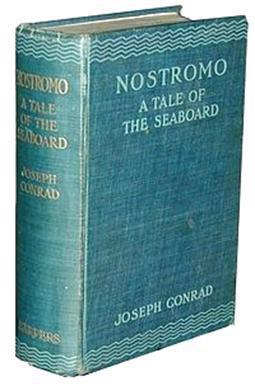

NOSTROMO

A TALE OF THE SEABOARD

This 1904 novel is set in the fictitious South American republic of “Costaguana.” and was originally published serially in two volumes of

T.P.’s Weekly

. Nostromo is believed by some to be the best novel of the 20

th

century.

The first edition

CONTENTS

PART FIRST THE SILVER OF THE MINE

TO JOHN GALSWORTHY

“So foul a sky clears not without a storm.” — SHAKESPEARE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

“Nostromo” is the most anxiously meditated of the longer novels which belong to the period following upon the publication of the “Typhoon” volume of short stories.

I don’t mean to say that I became then conscious of any impending change in my mentality and in my attitude towards the tasks of my writing life. And perhaps there was never any change, except in that mysterious, extraneous thing which has nothing to do with the theories of art; a subtle change in the nature of the inspiration; a phenomenon for which I can not in any way be held responsible. What, however, did cause me some concern was that after finishing the last story of the “Typhoon” volume it seemed somehow that there was nothing more in the world to write about.

This so strangely negative but disturbing mood lasted some little time; and then, as with many of my longer stories, the first hint for “Nostromo” came to me in the shape of a vagrant anecdote completely destitute of valuable details.

As a matter of fact in 1875 or ‘6, when very young, in the West Indies or rather in the Gulf of Mexico, for my contacts with land were short, few, and fleeting, I heard the story of some man who was supposed to have stolen single-handed a whole lighter-full of silver, somewhere on the Tierra Firme seaboard during the troubles of a revolution.

On the face of it this was something of a feat. But I heard no details, and having no particular interest in crime qua crime I was not likely to keep that one in my mind. And I forgot it till twenty-six or seven years afterwards I came upon the very thing in a shabby volume picked up outside a second-hand book-shop. It was the life story of an American seaman written by himself with the assistance of a journalist. In the course of his wanderings that American sailor worked for some months on board a schooner, the master and owner of which was the thief of whom I had heard in my very young days. I have no doubt of that because there could hardly have been two exploits of that peculiar kind in the same part of the world and both connected with a South American revolution.