Complete Works of Emile Zola (999 page)

Read Complete Works of Emile Zola Online

Authors: Émile Zola

“You are acting shamefully!” she cried. “I told you so before. You don’t seem to have any feelings! However, I can tell you this, unless you make a change, you may lie in your hole by yourself. I shall have myself taken somewhere else, for I’ll never consent to let my bones be poisoned by that drab there!”

As she spoke she jerked her chin in the direction of Flore; but the latter was not going to submit to this abuse.

“You’d be no very pleasant neighbour yourself!” she retorted, in a drawling, whining tone. “Make yourself quite easy, my dear; I don’t intend to let your bones give the disease to mine.”

“Eh, what? What disease?”

“Oh, you know what disease very well!”

La Bécu and La Frimat were now obliged to interpose and separate the two women.

“Come, come,” urged the former, “you won’t lie together since you are both of the same way of thinking. Every one is at liberty to choose her own company.”

La Frimat expressed her acquiescence in this.

“It’s only natural,” she said. “I’m sure that when my old man’s time comes I’d rather keep him in the house with me than let him lie alongside of old Couillot, with whom he had differences once on a time.”

The tears welled to her eyes as she thought that her paralytic husband would probably pass away before the week was over. She had fallen with him on the previous evening as she was trying to put him to bed, and whenever he departed she wouldn’t be long in following him.

It was at this moment that Delhomme came up, and Lengaigne at once appealed to him.

“Now, then,” said he, “folks say you are a just man; well, will you allow such injustice? Now that you are mayor, you can make this scamp turn out of here and take his place in the regular order.”

Macqueron shrugged his shoulders, and Delhomme proceeded to explain that as he had paid his money the plot belonged to him. The matter was settled now, and there was an end of it. Buteau, who had hitherto quieted himself by force, then lost his head and rushed into the fray. All the members of the family should have maintained a decorous bearing as the clods of soil were still falling with heavy thuds upon the old man’s coffin; however, Buteau’s indignation was too great to be restrained.

“Ah! curse it, you’re mightily mistaken if you expect to find any proper feeling in that fellow!” he cried to Lengaigne, as he pointed to Delhomme. “He let his own father be buried by the side of a thief!”

This remark caused a general explosion, the different members of the family taking part in the row. Fanny supported her husband, saying that the real mistake lay in not having purchased a plot for their father at the time when their mother Rose died; he might have laid close to her. Thereupon Hyacinthe and La Grande assailed Delhomme with abuse, also expressing their disgust at old Fouan’s proximity to Saucisse, a most inhuman proceeding admitting of no excuse whatever. Monsieur Charles was of the same opinion, but expressed himself more moderately.

They were now all wrangling and shouting at once. Buteau, however, managed to make himself heard above the others, as he roared out: “Yes, their very bones will struggle under the ground to attack each other again!”

The whole company, relatives, friends, and acquaintances, eagerly seized hold of this phrase. Yes, that was the truth! Their very bones would continue the fight underground. When they were buried, the Fouans would still pursue each other with that savage animosity which they had mutually manifested during life. Lengaigne and Macqueron would go on bickering and quarrelling till they had quite rotted; and the women, Cœlina, Flore, and La Bécu, would still attack each other with their tongues and claws. It was the universal opinion in Rognes that foes in life could never rest peacefully together when they were buried. The hatred between them never perished; it lasted beyond life right away to the end of time. In this sunny graveyard, beneath the rank growth of grass and weeds, a savage, timeless warfare was waging between coffin and coffin, just such a warfare as was now being waged by these living mortals who were grouped together amid the graves, clenching their fists and reviling one another. However, a shout from Jean separated the adversaries, and made them turn their heads: “La Borderie is on fire!”

Doubt was no longer possible. The flames were leaping up from the roof, quivering and paling in the light of day. A dense cloud of ruddy smoke was gently rolling away towards the north. Then La Trouille came into sight, running hastily from the direction of the farm. While hunting for her geese she had noticed the first sparks, and she had stood gloating over the spectacle till the idea of telling the others of the sight occurred to her, whereupon she set off at a run. Jumping astride the low wall, she cried out in her childish voice:

“Oh, isn’t it just blazing? That big beast Tron came back and set it on fire in three different places — in the barn, in the stables, and in the kitchen. They caught him just as he was setting the straw alight, and the waggoners nearly killed him. The horses and the cows and the sheep are all roasting! Oh, you should hear the noise they’re making! You never heard such a row!”

Her green eyes glistened, and she laughed as she continued:

“Oh, and there’s La Cognette! She’s been ill, you know, ever since the master died, and they had forgotten her in her bed. She was already getting singed, and she’d only just time to cut and run in her shift. Oh, it was a rare sight to see her prancing about in the open fields with her bare legs. She hopped and skipped along, and the folks shouted out, ‘hou! hou!’ as she passed them. They’re not very fond of her, you know, and one old man said: ‘She’s come out just as she went in, with only a shift on her back!’ “

At this point a fresh thrill of merriment made the girl wriggle with laughter.

“Do come! it’s such a lark! I’m off back again.”

Then she sprang down from the wall, and ran as fast as her legs could carry her in the direction of the blazing farm.

Monsieur Charles, Delhomme, Macqueron, and nearly all the peasants followed her; while the women, with La Grande at their head, also left the graveyard for the road, so as to get a better view. Buteau and Lise had stayed behind, and the latter detained Lengaigne, being anxious to question him about Jean, without appearing to show too much interest in him. Had he found some work, she asked, as he was lodging in the neighbourhood? When the innkeeper replied that he was going away to re-enlist, both Buteau and Lise, feeling vastly relieved, broke out into the same exclamation:

“What a fool he must be!”

So this troublesome bother was at an end, and they would be able to live happily again! They cast a last glance at Fouan’s grave, which the sexton had now almost filled up; and as the two children lingered behind to watch, their mother called them.

“Come along, Jules and Laure, come along! Mind you’re good children, now, and do what you’re told, or the man will come and put you in the earth too.”

The Buteaus then went off, pushing Laure and Jules in front of them. The children, who knew the truth, looked very grave and earnest with their big solemn black eyes.

Jean and Hyacinthe were now the only ones left in the graveyard. The latter just watched the fire from a distance, disdaining to hurry off like the others. As he stood, quite motionless between two graves, he seemed to be absorbed in some visionary dream, and his sad, dissipated face expressed the mournful melancholy that lies at the end of every system of philosophy. Perhaps he was thinking that existence glides away and vanishes like smoke! And as serious meditation always had an exciting effect on him, he ended by giving vent to three detonations.

“God in heaven!” exclaimed the drunken Bécu, as he passed through the graveyard on his way to the fire, “if this wind continues, we may expect a downfall of dung!”

“Yes, indeed,” replied Hyacinthe; and hurrying off he disappeared round the wall.

Jean was now alone. Away in the distance some huge whirling clouds of black smoke were rising from the ruins of La Borderie, casting shadows over the fields and the scattered sowers, who were still plodding backwards and forwards, making the same monotonous gestures. Then Jean’s eyes slowly wandered back to the ground at his feet, and he gazed at the mounds of fresh soil beneath which Françoise and old Fouan were sleeping. His anger of the morning and his disgust for people and circumstances had vanished in a feeling of profound calm. In spite of himself he felt full of restfulness and hope; maybe it was owing to the warm sunshine.

Ah, yes, his master Hourdequin had had any amount of worry with all those new inventions; he had never reaped much advantage from his machines and artificial manures, and other scientific devices. And then La Cognette had come to finish him off; he was now asleep in the graveyard, and nothing remained of the farm, the very ashes of which the wind was now sweeping away. But what did it matter after all? Walls might be burned down, but the soil could not be burned. Earth, Mother earth, would always be there ready to nourish all who cast their seed upon her bosom. She had time enough before her, and space in plenty, and even now she yielded corn, and would yield still more when men knew how to treat her.

It was the same with the stories of the revolutionists — those political cataclysms which were predicted. The soil, it was said, would pass into other hands, and the harvests of other countries would swamp our own, till our land was over-run with brambles. Well, and what then? Is it within any one’s power to harm the soil? It will always be there for any one who may be obliged to till it to escape dying from hunger. And even if weeds were to cover its surface for years together, that would be a rest for it, and it would grow young and fertile again. The soil cares nothing about our quarrels; this mighty toiler, ever absorbed in her workings, troubles herself no more about man than about a swarm of ants.

Jean had had his share of grief and trouble, pain and rebellion. And now Françoise was slain, Fouan was slain, the wicked seemed triumphant, the foul and sanguinary vermin of the villages were able to pollute and prey upon the soil. Ah, but who can tell? The frost which sears the crops, the hail which breaks them, the deluge which beats them down, are all perhaps necessary, and so it may be that blood and tears are equally essential to the world’s progress. What does our unhappiness weigh in the great system of the stars and the sun? We only gain our bread by dint of a terrible daily struggle. The soil alone remains fixed and imperishable, the mother from whom we all spring, and to whom we must all return; she whom her children love so keenly that they sin for her sake; she who utilises everything, even our crimes and our wretchedness, for purposes of creation, in view of attaining her own secret, mysterious ends.

For a long time some such confused, ill-formulated reverie as this rolled vaguely through Jean’s mind as he lingered in the graveyard; but suddenly a trumpet sounded in the distance, the trumpet of the firemen of Bazoches-le-Doyen, who were arriving too late at the double-quick. Then, hearing the clarion-call, Jean drew himself up. It was like warfare passing by amid smoke; warfare with its horses, its cannons, and its clamorous carnage! Ah! confound it, since he no longer had the heart to till the old soil of France, he would defend it from invaders!

He was going off, when for a last time he turned his eyes from the two grassless graves to the endless plough-lands of La Beauce filled with sowers, all making the same ceaseless gesture. Mid corpses and seeds, sustenance was springing from the soil.

THE END

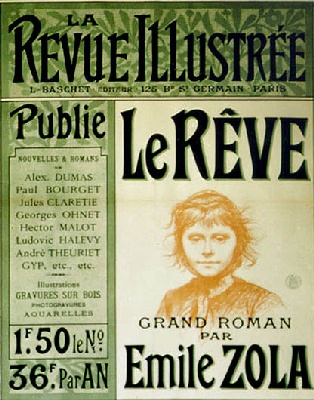

THE DREAM

Translated by Eliza E. Chase

Le Rêve

is the sixteenth novel in the

Rougon-Macquart

series, first published by Charpentier in October 1888, recounting the story of the orphan Angélique Marie, who is adopted by the Huberts, a couple of embroiderers. The Huberts’ marriage has been blighted by a childlessness, which they believe is due to an old a curse uttered by Mme Hubert’s mother on her deathbed.

Angélique is a humble and devout girl, enthralled by the tales of the saints and martyrs, as told in the Golden Legend of Jacobus de Voragine. She dreams of being saved by a handsome prince and living happily ever after, in the same way the virgin martyrs have their faiths tested on earth before being rescued and married to Jesus in heaven. When she meets and falls in love with Félicien d’Hautecœur, the last in an old family of knights in the service of Christ and of France, it appears her dream has been realised.