Complete Short Stories (VMC)

Read Complete Short Stories (VMC) Online

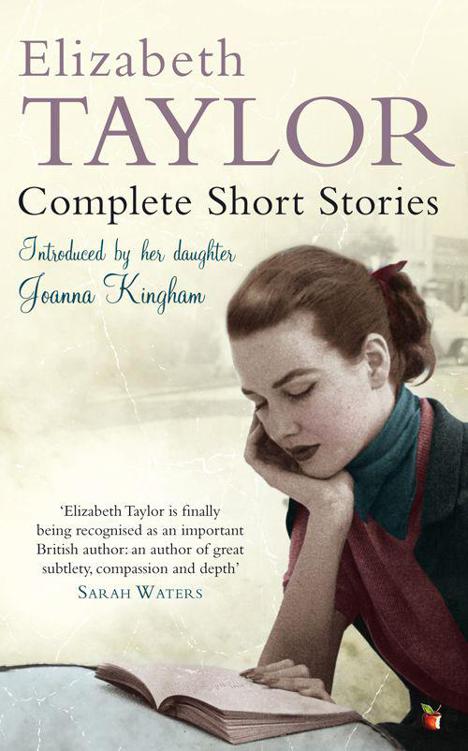

Authors: Elizabeth Taylor

VIRAGO

MODERN CLASSICS

564

Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Taylor (1912–1975) is increasingly being recognised as one of the best writers of the twentieth century. She wrote her first book,

At Mrs Lippincote’s

, during the war while her husband was in the Royal Air Force, and this was followed by eleven further novels and a children’s book,

Mossy Trotter

. Her highly acclaimed short stories appeared in publications including

Vogue

, the

New Yorker

and

Harper’s Bazaar

, and here for the first time are collected in one volume. Rosamond Lehmann considered her writing ‘sophisticated, sensitive and brilliantly amusing, with a kind of stripped, piercing feminine wit’, and Kingsley Amis regarded her as ‘one of the best English novelists born in this century’.

At Mrs Lippincote’s

Palladian

A View of the Harbour

A Wreath of Roses

A Game of Hide and Seek

The Sleeping Beauty

Angel

In a Summer Season

The Soul of Kindness

The Wedding Group

Mrs Palfrey at the Claremont

Blaming

Short Story Collections

Hester Lilly and Other Stories

The Blush and Other Stories

A Dedicated Man and Other Stories

The Devastating Boys

Dangerous Calm

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-1-40551-271-8

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 the Estate of Elizabeth Taylor

Introduction copyright © 2012 Joanna Kingham

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

Nods & Becks & Wreathèd Smiles

I Live in a World of Make-believe

The Rose, the Mauve, the White

You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There

Most of the stories in this book were originally published in four volumes –

Hester Lilly

(1954);

The Blush

(1958);

A Dedicated Man

(1965); and

The Devastating Boys

(1972) – but this edition includes several that have previously appeared only in magazines. Much of my mother’s work was printed in the

New Yorker

, and I can remember the copies, with a deep crease down the centre, regularly arriving at our house. The crease was so that the parcel would qualify for printed-paper-rate postage, and it was only when I went to America in my teens that I saw for the first time flat copies on the bookstalls – they seemed strangely unfamiliar. My brother and I enjoyed the cartoons and later the articles and short stories, including our mother’s own. We also enjoyed the

New Yorker

’s generous gifts of a large ham at Christmas-time, a great treat when such things were scarce here. The literary editors Katharine White and William Maxwell became my mother’s good friends, and she dedicated

The Blush

to Maxwell.

Before writing this introduction I had been reading the collections, smiling at forgotten memories and wishing I could ask my mother about several of the details and incidents and what had prompted her to include them. Many of the stories have an autobiographical streak, though sometimes no more than a thread; but throughout there are phrases and characters recognisable to those of us lucky enough to have known her. Two such tales are ‘Plenty Good Fiesta’ and ‘The Devastating Boys’. The little Spanish boy she wrote about in ‘Plenty Good Fiesta’ eventually returned to his family in Spain, while ‘Sep’ and ‘Benny’ of ‘The Devastating Boys’ were frequent visitors at my parents’ house. It is nearly fifty years since they first came, but they kept in touch with my father until his death a few years ago. My mother’s fears about how she would manage to look after the children she reflected on as she wrote about Laura’s doubts, but in fact my mother had an intuitive understanding of children and invariably elicited their love and respect. It has always struck me how shrewdly they are portrayed in her fiction. Once, in a letter to her agent, she reported that she was having difficulty in finding new ideas for her work, but had been delighted when my small daughter had told her

not to worry as it would ‘soon come down from your head’ – a sage counsel which much cheered her grandmother.

Readers frequently ask about a writer’s technique – how they develop their characters, use dialogue and so on. In an article, my mother once described how she set the scenes for her stories: ‘The thing that I do, I have found, is to fasten to some detail, and then let the mind wander down any corridor it fancies, opening doors or ignoring them. There was once a blind man I saw on a bus. From that, watching him, wondering about him, I built up a whole story.’ This was the ‘Spry Old Character’. The man she described lived in a home for the blind on the edge of our village, and each afternoon was picked up by the same bus that I caught home from prep school. While the bus waited at the terminus on the common he would chat cheerily to the driver and conductor before being delivered safely back to his usual stop. Meanwhile, I would make my way to our house and, tucking into my tea, would listen to my mother read aloud to me – usually from E. Nesbit or Noel Streatfeild. She was a good reader, and listening to her encouraged me to follow the practice with my own children – and grandchildren.

The title ‘You’ll Enjoy It When You Get There’ came from a much-used family expression and an assurance frequently delivered to me when, after dressing for a party or the Pony Club dance (which naturally recalls another story, ‘The Rose, the Mauve, the White’), I would start to say that I couldn’t face it. My parents were wrong in their assertion, as I rarely did enjoy those occasions. What inspired the story, though, was what happened to my mother at a rather stiff trade function with my father. Like me, she didn’t enjoy it when she got there, and then humiliated herself by making the mistake of telling one poor bored man all about the adventures of her Burmese cat … twice. Such was her ennui that she had never noticed his face, only the glittering chain of office resplendent on his chest. This little social gaffe distressed her, but I am ashamed to say that we, unsympathetically, delighted in the story.

There was a lot of laughter and leg-pulling in the family and my parents were very funny. I will always remember our joy at my father’s indignant reaction when the publishers had advised my mother to change the name of Muriel in ‘Hester Lilly’. ‘You can tell them from me that before I met you I very nearly married a girl called Muriel,’ he said, and after a pause added: ‘and I’ll have you know that she was a very good swimmer.’

On one occasion when we were making the beds and listening to the morning story on the radio, my mother stopped what she was doing and said, ‘This is strange, I know this story.’ She then realised that it was one of her own. We heard later that a man had been submitting stories from the

New Yorker

to the BBC as his work, never imagining anyone in Britain

would recognise them. That was not the only unwelcome surprise my mother was to have from the morning story programme. In 1959, ‘Swan-moving’ was scheduled to be broadcast, and when it was over, she wrote to a friend: ‘After about a minute of rather stilted reading and slurred words, he suddenly stopped and began to mutter to himself about cuts he should have made – a silence – almost endless to me – and then he asked someone if he should start again. Another pause, and then an announcer said there seemed to be some trouble with the cuts that should have been made, and then played some gramophone records instead. Perhaps the poor man was taken ill. A woman on the bus wondered if I had written something rude, and, coming upon it for the first time, he had thought it better not to read it.’

The collection

A Dedicated Man

was inscribed to the writer Robert Liddell, with whom my mother maintained a friendship that began with a long correspondence. As he lived and worked in Athens, it was some time before they actually met. We had visited Greece in the 1950s, but it was not until later when my mother was in Athens alone that she finally met him. And although she was certainly nervous, their first meeting was unlike the one between Edmund and Emily that she portrays in ‘The Letter-writers’. Robert, however, makes reference to it in his book

Elizabeth and Ivy

, which is about their shared friendship with Ivy Compton-Burnett. After the colonels took over the government, my mother declined to go to Greece again; instead, she and my father would visit the area on cruises, and Robert would come aboard at various ports to see them.