Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd (36 page)

Read Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd Online

Authors: Mark Blake

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Composers & Musicians, #Music, #History & Criticism, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

Hearing

Dark Side of the Moon

for the first time had also inspired another film-maker, the band’s old Cambridge confederate Anthony Stern. Since 1967, Stern had returned repeatedly to the film ideas he and Syd Barrett had devised under the title of ‘The Rose-Tinted Monocle’. ‘I dug out all this footage and it worked perfectly with

Dark Side of the Moon

,’ says Anthony. Having borrowed a film projector from David Gilmour, he arranged to visit each member of the band and show them his film, with a view to using

Dark Side of the Moon

as its soundtrack.

‘They knew that Syd had been involved with the roots of the film, and on a purely aesthetic and creative level they all gave it the thumbs up. They all said, “Of

course

you can use

Dark Side of the Moon

for this”,’ laughs Anthony. ‘I came home elated. It had taken me about two weeks to get to see them all. Roger, despite his immense ego, was incredibly friendly, warm and enthusiastic about the idea of me using this music in such an abstract, non-commercial way. I think that appealed to him.’

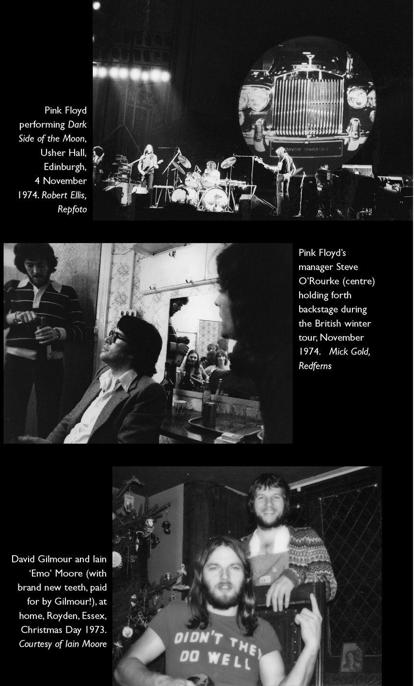

Before long, though, the project would hit the buffers. ‘The thing collapsed when I went to see Steve O’Rourke. I showed him the film. He looked at it completely impassively and finally said, “Anthony, I just don’t

get

it. This is not the sort of imagery I see associated with Pink Floyd . . . I see jets taking off . . . I see New York skyscrapers . . .”’

Interviewed two years earlier, Richard Wright had expressed a fear that the Floyd were ‘in danger of becoming slaves to our equipment ... Sometimes I look at our huge truck and tons of equipment and think: Christ, all I’m doing is playing an organ.’ Pink Floyd’s entourage had grown even more since then.

Maintaining the arsenal of sound and light equipment required an army of stagehands and technicians. By 1974 the key roles now fell to Mick Kluczynski, a stocky Scotsman of Polish origins, who had joined his old friend Chris Adamson to help take care of the sound as part of the so-called ‘Quad Squad’. Like Adamson, and his potato-eating stunt, Roger Waters later recalled Kluczynski consuming twenty-eight fried eggs as a bet before having to throw up. The bassist also challenged Kluczynski to drink a pint of whiskey during a day off on tour in America. Elsewhere, Robbie Williams was now on board as stage technician. Williams was noted for having, in the words of a fellow crew member, ‘a very deep voice from right down in his boots’, which had prohibited him from being one of the interviewees on

Dark Side of the Moon

. Elsewhere, the numbers were made up with new recruit, Phil Taylor, who would go on to become David Gilmour’s long-serving guitar technician. Kluczynski and Williams would later head up their own production companies, and continue to work with Pink Floyd in the 1990s.

Alongside Dick Parry, Floyd were now joined by backing singers Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams, collectively known as The Blackberries.

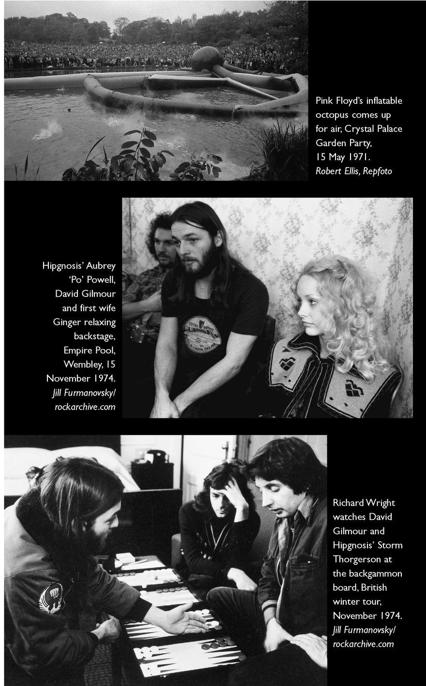

The tour opened on 4 November with two dates at Edinburgh’s Usher Hall. The set would comprise just five pieces: ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’, ‘Raving and Drooling’, ‘You Gotta Be Crazy’,

Dark Side of the Moon

and an encore of ‘Echoes’. The visual extravaganza would begin with

Dark Side of the Moon

. For ‘Speak to Me’, an image of the moon was projected on the huge circular screen, growing bigger and bigger with each heartbeat, until it filled the entire screen. ‘On the Run’ would be illustrated with aircraft landing lights and flashing police lights before switching to swooping bird’s-eye footage of a city landscape and various explosions. Airborne clocks accompanied ‘Time’, George Greenough’s magnificent surfer appeared for ‘The Great Gig in the Sky’, and a quick-fire display of Lear jets and banknotes flashed up on the screen during ‘Money’.

The logistics of such a big production brought with it another set of problems. ‘The equipment was pretty unreliable,’ recalled Wright. ‘The film would break or the projector would break. There were a lot of missing cues and trying to get back in time. We were always getting snappy with the technicians.’ A review in

New Musical Express

of the opening night complained about the malfunctioning sound system, too much feedback and ‘David Gilmour’s dreadful singing on the new material’.

Floyd’s refusal to play the media game is best summed up by Gilmour’s recent explanation: ‘Once we realised we could sell records and tickets without having to talk to the press, we chose not to.’

Melody Maker

’s Chris Charlesworth sidestepped the band’s refusal to give him a ticket for the Edinburgh show by buying one from a tout and talking his way into a post-gig supper with the band. The day after, he managed to get an interview with Richard Wright, much to the displeasure of the rest of the group, especially Roger Waters, who was still smarting from a comment made by the keyboard player in a previous interview, suggesting that the Floyd’s lyrics weren’t that important.

Wright’s remarks in the subsequent

Melody Maker

article suggested a very insular attitude, even by Floyd standards: ‘I don’t listen to what is being played on the radio. I don’t watch

Top of the Pops

. I don’t watch

The Old Grey Whistle Test

. I don’t even know how the rock business is going . . .’

An even greater shock to Charlesworth was the news that the band were choosing their hotels on the basis of how near they were to decent golf courses. ‘I recall being astonished that Waters played golf,’ he later wrote. ‘It seemed the unlikeliest of pastimes for a man whose lyrical preoccupations were space flight, insanity and death.’ As well as golf, Waters was also a keen squash player, with Gilmour his closest challenger in the band.

In his own memoir, Nick Mason (the band’s worst squash player, according to some) was admirably frank about the problems now besetting the Floyd. ‘We seemed to be more interested in booking squash courts than perfecting the set,’ he wrote. ‘We were demonstrating a distinct lack of commitment to the necessary input required.’

After the glamour and glitz of New York’s Radio City Hall, a trawl through Great Britain’s provincial theatres in a cold, wintry November must have seemed less enticing. Meanwhile, in the real world, the IRA blew up a pub in Birmingham a couple of weeks before the band were due in town, ramping up the paranoia and general unease. Inside the Floyd bubble, there was uncertainty about the new material, frustrations with their own or others’ performances, and a sense that the visual rather than musical aspect of the show was now becoming too important.

In early 1974, cinema projectionist Pete Revell answered an ad in

Melody Maker

, and found himself being interviewed by Arthur Max for the job of projectionist in the Floyd’s road crew. (‘I was shocked to discover it was for Pink Floyd, as it was the smallest, cheapest ad you could possibly buy.’)

‘There was always a vibe around Roger,’ says Revell now. ‘Everybody felt it on that tour, even, I think, the band. David was a real gentleman and Rick was away in his own quiet world, but Roger was so bloody aloof, so far up his own arse.’ Nick Mason was also well liked, though Revell recalls that the drummer’s request to a crew member to buy him a half-inch drive socket set during an afternoon off in Bristol went ignored. The crew spent the day in the pub, wondering why Mason needed a half-inch drive socket set for his drum kit. Later, the penny dropped, when the drummer screeched up to the band’s hotel in his new toy, a second-hand Ferrari.

Problems within the crew were also having an impact. The band’s newly acquired mixing desk proved a temperamental beast, and front-of-house sound engineer Rufus Cartwright was let go after just a few dates. Order was restored by his replacement, Brian Humphries, who had worked at Pye Studios and engineered the

More

soundtrack. But Arthur Max, the band’s brilliant, if fiery-tempered lighting wizard, would also find his days numbered, as the fractious atmosphere took its toll.

Day after day they would be confronted with new stories about Max’s run-ins with crew members and venue officials. ‘I walked out twice - told him to shove the job,’ recalls Pete Revell of the friction amongst the crew (often involving Arthur). ‘They sent Steve O’Rourke round to my house to talk me into coming back.’

Max’s last Pink Floyd gig would be at the Sophia Gardens Pavilion in Cardiff. His deputy, the more emollient Graeme Fleming, would take his place. After Fleming’s debut at the Liverpool Empire, Waters would inform the crowd that this had been the best gig of the tour. ‘The Liverpudlians thought it was something to do with them,’ says Revell, ‘but really it was because they had all stopped rowing.’ The Floyd’s outspoken lighting designer would eventually go on to a glittering career in Hollywood as a movie art director, winning an Oscar nomination for his work on Ridley Scott’s blockbuster

Gladiator

.