Come Out Smokin' (13 page)

One day less than a month after the big fight, Joe Frazier returned to South Carolina. He was going home, but this time it was at the invitation of the state.

The governor, John C. West, had invited Joe to come home and become the first black man since the Reconstruction Era more than a century before to address the South Carolina legislature in Columbia, the state capital.

His wife and two of his five children were there and so were one of Joe's sisters and one of his brothers and his mother, Dolly, who kept thinking how proud her husband would have been if he could have been there; how proud Rubin would have been of his “special” son.

Early in the day, the champion and his family were presented to Governor West, who gave Frazier a silver and black jewel box wrapped in gold paper.

“Congratulations,” the governor said. “We're all proud of you in South Carolina.”

“All righty,” Frazier said as he unwrapped the package. “I appreciate that.”

Later, as he entered the State House, Frazier was greeted with a thirty-second ovation by the legislators. Again, he was applauded when he was introduced.

He was neatly dressed in a conservative gray suit with a thin blue stripe, a yellow shirt and a red, tan, and blue tie. The applause subsided when he reached the podium.

“I want to thank the honorable Senator Gasque for that introduction,” he said, “and to thank Governor John West for inviting me to speak to this Assembly.

“Today, as I stand before you, I will not deny that I am a proud and happy man . . . and yet somewhat sad, and a little hurt to know that I am one of the very few black citizen guests to address this General Assembly in almost a century . . .

“With South Carolina being so big and beautiful and of course having so many wonderful black citizens, there must have been more black men or black women also deserving of this honor.

“As I stand here and look around this chamber, I can see that South Carolina has come a long way since I left Beaufort eleven years ago.

“I remember working on the farm when I was a boy. I'd say, âGood morning, boss,' and he'd say, âTo the mule.' At noon, I'd say, âLunch time, boss,' and he'd say, âOne o'clock.' And in the evening, I'd say, âGood night, boss,' and he'd say, âIn the mornin'.' ”

There was a burst of laughter and spontaneous applause from the House chamber and Frazier paused, then continued.

“I am proud to see the few black faces that have been duly elected to this legislature and it gives me great pleasure to know that finally white and black citizens are working together for the betterment of its people. . . . And also last week, to my great satisfaction, I read where a black student was elected president of the student body at the University of South Carolina . . .

“But ladies and gentlemen, I am here today not as an orator or as a statesman, but as a young man whose boyhood dream was realized when I won the heavyweight championship of the world.

“You can do anything you want to do if you really put your heart and soul and mind into it. When I started boxing, I had two jobs, a wife, a couple of kids, and I had to train. But if you put your right foot in front of you and the left behind, somebody will give you a hand.

“Of course, being a black boxing champion is nothing new. There have been many great boxing champions of color, Joe Louis being one of the greatest . . . and all of us have been fighting for the same thingâprogress.

“And to prove once again to all humanity that if given the opportunity . . . what we can accomplish . . . we are making progress slowly . . . much too slowly, in fact.

“But seeing the progress of the black man during my lifetime whether it be in South Carolina, where I was born twenty-seven years ago, or in New York City has suddenly become so much more important to me.

“And every time I see a black young college graduate it makes me feel good because then I know we have struck another blow in the right directionâa blow at poverty, unemployment, and hungerâall of which still exist in my hometown of Beaufort.

“I mean we must save our people . . . and when I say our people, both black and white . . . especially our youth . . . the future leaders of our great country that are being afflicted by drug abuse. We need to quit thinking who's living next door, who's driving a big car, who's my little daughter going to play with, who is she going to sit next to in school. We don't have time for that.

“Let's all pull together. . . . Let's make South Carolina a nice place to live, and Philadelphia and New York, so that we can live together, play together, and pray together.

“And let me remind you that the best help our youth can receive can start right here in every legislative chamber in these great United States.

“We need to build our youth and care about our youthâfor without them, there can be no future . . . boxing taught me that mostly tired people make mistakes . . . strong minds and healthy bodies seldom do.

“So, in conclusion, let me sayâit is us, you and me, all men together, we must fight and whip the problems of South Carolina and our great country.

“It is true that we have come a long way . . . but, gentlemen, we still have a long way to go. . . . Let us try and go together. . . .

“Thank you. . . .

The speech took twelve minutes and as Joe Frazier, an uneducated black man, spoke to an august group of South Carolina lawmakers, many of them twice his age, there was rapt attention. And when it was over, the applause in the House chamber was deafening as Joe Frazier, heavyweight champion of the world, child of poverty, walked proudly down from the podium.

* * *

In the days that followed his great victory over Muhammad Ali, there was much talk about a rematchâmost of it from Ali. The beaten champion began his campaign the very next day, insisting he had won the fight, that he had thrown more punches, scored more points, inflicted more damage. He supported his arguments with postfight pictures in the morning newspapers, pictures that showed Joe Frazier's face, lumpy and beaten out of shape.

“Look at me,” he insisted. “Look at my face. Except for this swelling, there's not a mark on me.”

The campaign grew in intensity, especially after Joe Frazier slipped into a Philadelphia hospital, where he stayed almost three weeks. First reports were ominous and rumors had the heavyweight champion of the world near death.

His blood pressure had risen and he had a kidney ailment, but apart from that, what he needed was complete rest. He was exhausted, emotionally and physically exhausted.

Still, there were rumors that Joe Frazier would never fight again, but four months after his fight with Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier was back in his gym in Philadelphia boxing, hitting the light bag, doing calisthenics and insisting that if Ali wanted more, he would be only too happy to oblige.

No matter. Fight again or not, beat Ali again or not, Joe Frazier would never stand with the great champions of all time. He would never have the appeal of a Jack Dempsey or a Muhammad Ali. He would never become the second Joe Louis in public acceptance.

But he worked hard and he provided well so that his children would have a better life than he did. And he became one of only twenty-four men in modern boxing history to hold the heavyweight championship of the world. That is one thing they could never take away from him. That's all Joe Frazier ever really wanted.

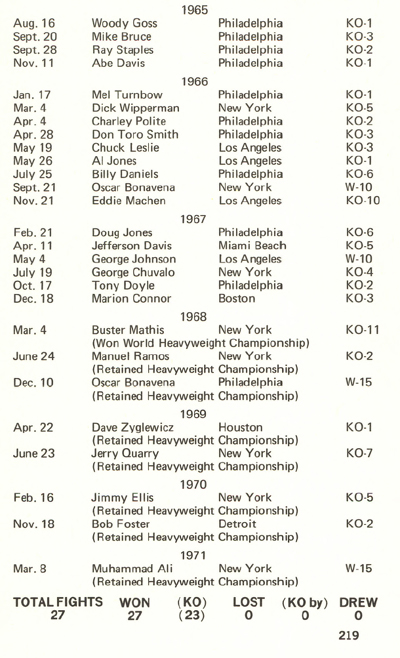

(Courtesy of

Ring

magazine's

Encyclopedia and Record Book

)

Feb. 7, 1882âPaddy Ryan was knocked out by John L. Sullivan at Mississippi City, 9 rounds. Referees, Col. Alex. Brewster and Jack Hardy (2).

July 8, 1889âJohn L. Sullivan beat Jake Kilrain, seventy-five rounds, Richburg, Miss. (last championship fight, bare knuckles). Sullivan scaled 198; Kilrain, 195. Referee, John Fitzpatrick.

Sept. 7, 1892âJames J. Corbett defeated John L. Sullivan at New Orleans, 21 rounds. (Used big gloves for first time). Sullivan weighed 212; Corbett, 178. Referee, Prof. John Duffy.

Jan. 25, 1894âJames J. Corbett knocked out Charley Mitchell, Jacksonville, Fla., three rounds. Corbett, 184, Mitchell, 158. Referee Honest John Kelly.

Mar. 17, 1897âBob Fitzsimmons knocked out James J. Corbett, Carson City, Nevada, 14 rounds. Corbett, 183; Fitzsimmons, 167. Referee, George Siler.

June 9, 1899âJames J. Jeffries knocked out Bob Fitzsimmons, Coney Island, N. Y., 11 rounds. Jeffries, 206; Fitzsimmons, 167. Referee, George Siler.

Nov. 3, 1899âJames J. Jeffries defeated Tom Sharkey on points, Coney Island, N. Y., 25 rounds. Jeffries, 215; Sharkey, 183. Referee, George Siler.

May 11, 1900âJames J. Jeffries knocked out James J. Corbett, Coney Island, N. Y., 23 rounds. Jeffries, 218; Corbett, 188. Referee, Charley White.

Nov. 15, 1901âJames J. Jeffries stopped Gus Ruhlin, San Francisco, 5 rounds. Sponge tossed in ring after bell ended the fifth round. Referee Harry Corbett.

July 25, 1902âJames J. Jeffries knocked out Bob Fitzsimmons, San Francisco, 8 rounds. Jeffries, 219; Fitzsimmons, 172. Referee, Ed Graney.

Aug. 14, 1903âJames J. Jeffries knocked out James J. Corbett, San Francisco, 10 rounds. Jeffries, 220; Corbett, 190. Referee, Ed Graney.

Aug. 25, 1904âJames J. Jeffries knocked out Jack Munroe, San Francisco, 2 rounds. Jeffries, 219; Munroe, 186. Referee, Ed Graney.

Lack of opposition forced Jeffries into retirement in March, 1905. He then named Marvin Hart and Jack Root as the leading contenders and agreed to referee their fight at Reno, Nev., July 3, 1905, with the stipulation that he would term the winner the world heavyweight champion. Hart stopped Root in 12 rounds. Hart, 190; Root, 171.

Feb. 23, 1906âTommy Burns defeated Marvin Hart, Los Angeles, 20 rounds. Burns, 180; Hart, 188. Referee, Jim Jeffries.

Burns laid claim to the world title.

Another claimant to the throne was Philadelphia Jack O'Brien, who, on Nov. 28, 1906, at Los Angeles, had fought Burns a 20 round draw, with Jim Jeffries as referee. Burns weighed 172; O'Brien, 163½.

May 8, 1907âTommy Burns eliminated Jack O'Brien by defeating him at Los Angeles, 20 rounds. Burns, 180; O'Brien, 167. Referee, Charles Eyton. Burns was generally acknowledged as world champion.

July 4, 1907âTommy Burns knocked out Bill Squires, Colma, 1 round. Burns, 181; Squires, 180. Referee, James J. Jeffries.

Dec. 2, 1907âTommy Burns knocked out Gunner Moir, London, 10 rounds. Burns, 177; Moir, 204. Referee, Eugene Corri.

Feb. 10, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Jack Palmer, London, 4 rounds. Referee, Eugene Corri.

Mar. 17, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Jem Roche, Dublin, 1 round. Referee, R. P. Watson.

Apr. 18, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Jewey Smith, Paris, 5 rounds.

June 13, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Bill Squires, Paris, 8 rounds. Burns, 184; Squires, 183.

Aug. 24, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Bill Squires, Sydney, New South Wales, 13 rounds. Burns, 181; Squires, 184. Referee, H. C. Nathan.

(These victories clinched world recognition for Burns.)

Sept. 2, 1908âTommy Burns knocked out Bill Lang, Melbourne, Australia, 2 rounds. Burns, 183; Lang, 187. Referee, Hugh McIntosh and Promoter.

Dec. 26, 1908âJack Johnson knocked out Tommy Burns, Sydney, New South Wales, 14 rounds. Johnson, 192; Burns, 168. Referee and Promoter, Hugh McIntosh. Police stopped fight.

May 19, 1909âJack Johnson and Philadelphia Jack O'Brien fought six rounds, Philadelphia. No decision. Johnson, 205; O'Brien, 161.

June 30, 1909âJack Johnson and Tony Ross fought 6 rounds, Pittsburgh. No decision. Johnson, 207; Ross, 214.

Sept. 9, 1909âJack Johnson fought 10 rounds, no decision, with Al Kaufmann, San Francisco, Johnson, 209; Kaufmann, 191. Referee, Ed Smith.

Oct. 16, 1909âJack Johnson knocked out Stanley Ketchel, Colma, Cal., 12 rounds. Johnson, 205½; Ketchel, 170¼. Referee, Jack Welch.

July 4, 1910âJack Johnson knocked out Jim Jeffries, Reno, Nevada, 15 rounds. Referee and Promoter, Tex Rickard. (Jeffries came out of retirement in an effort to regain title, but failed.) Johnson, 208; Jeffries, 227.

July 4, 1912âJack Johnson won from Jim Flynn, 9 rounds, Las Vegas, N. M. Johnson, 192½; Flynn, 175. Referee, Ed Smith. (Police stopped bout.)

1913âJack Johnson had trouble with the U. S. Government during latter part of 1912, which resulted in the heavyweight champion going to Europe and remaining in exile for several years. In the interval a tourney was held in Los Angeles, Cal., and Luther McCarty, after defeating Al Kaufmann, Jim Flynn and Al Palzer, was proclaimed champion heavyweight of America.

On May 24, 1913, at Calgary, Canada, McCarty collapsed in the first round of a bout with Arthur Pelkey, and died from a brain hemorrhage. Ed Smith, referee.

Nov. 28, 1913âJack Johnson knocked out Andre Sproul, 2 rounds, Paris, France. Referee, Georges Carpentier.

Dec. 19, 1913âJack Johnson drew with Battling Jim Johnson, Paris, France, 10 rounds. (Referee called it a draw when Jack Johnson declared he had broken his arm.) June 27, 1914âJack Johnson defeated Frank Moran, Paris, France, 20 rounds. Johnson, 221; Moran, 203. Referee, Georges Carpentier.

Jan. 1, 1914âGunboat Smith won American heavyweight title by knocking out Arthur Pelkey in 15 rounds, San Francisco, Calif. Referee, Ed Smith.

July 16, 1914âGeorges Carpentier won American heavyweight title from Gunboat Smith on a foul, 6 rounds, London, England. Referee, Eugene Corri.

April 5, 1915âJess Willard knocked out Jack Johnson, Havana, Cuba, 26 rounds. Willard, 230; Johnson, 205½. Referee, Jack Welch.

March 25, 1916âJess Willard fought 10 rounds with Frank Moran, New York City. No decision. Willard, 225; Moran, 203. Referee, Charley White.

July 4, 1919âJack Dempsey knocked out Jess Willard, Toledo, Ohio, 3 rounds. Dempsey, 187; Willard, 245. Referee, Ollie Pecord.

Sept. 6, 1920âJack Dempsey knocked out Billy Miske, Benton Harbor, Michigan, 3 rounds, Dempsey, 185; Miske, 187. Referee, Jack Dougherty.

Dec. 14, 1920âJack Dempsey knocked out Bill Brennan, New York City, 12 rounds. Dempsey, 188¼; Brennan, 197. Referee, H. Haukaup.

July 2, 1921âJack Dempsey knocked out Georges Carpentier, Jersey City, N. J., 4 rounds. Dempsey, 188; Carpentier, 172. Referee, Harry Ertle.

July 4, 1923âJack Dempsey won on points from Tom Gibbons, Shelby, Montana, 15 rounds. Dempsey, 188; Gibbons, 175½. Referee, Jack Dougherty.

Sept. 14, 1923âJack Dempsey knocked out Luis Firpo, New York City, 2 rounds. Dempsey, 192½; Firpo, 216½. Referee, Jack Gallagher.

Sept. 23, 1926âGene Tunney won world's heavyweight title from Jack Dempsey on points, Philadelphia, 10 rounds. Dempsey, 190; Tunney, 189½. Referee, Pop Reilly. Judges, Mike Bernstein and Frank Brown.

Sept. 22, 1927âGene Tunney again defeated Jack Dempsey on points, Chicago, Ill., 10 rounds. Dempsey, 192½; Tunney, 189½. Referee, Dave Barry. Judges, Commodore Sheldon Clark and George Lytton.

July 26, 1928âGene Tunney knocked out Tom Heeney, New York City, 11 rounds, and the following week he announced his retirement. Tunney, 192; Heeney, 203½. Referee, Ed Forbes.

June 12, 1930âMax Schmeling and Jack Sharkey fought for the right to occupy heavyweight throne vacated by Tunney, New York City. In round 4 Schmeling was declared winner on a foul. Schmeling, 188; Sharkey, 197. Referee, Jim Crowley.

July 3, 1931âMax Schmeling stopped Young Stribling, Cleveland, Ohio, 15 rounds. Schmeling, 189; Stribling, 186½. Referee, George Blake.

June 21, 1932âJack Sharkey defeated Max Schmeling on points, Long Island City, 15 rounds. Sharkey, 205; Schmeling, 188. Referee, Gunboat Smith.

June 29, 1933âPrimo Carnera knocked out Jack Sharkey, Long Island City, 6 rounds. Carnera, 260½; Sharkey, 201. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Oct. 22, 1933âPrimo Carnera defeated Paulino Uzcudun on points, Rome, Italy, 15 rounds. Carnera, 259½; Uzcudun, 229¼. Referee Maurice Nicord.

March 1, 1934âPrimo Carnera defeated Tommy Loughran on points, Miami, Florida, 15 rounds. Carnera, 270; Loughran, 184. Referee, Leo Shea.

June 14, 1934âMax Baer knocked out Primo Carnera, Long Island City, 11 rounds. Baer, 209½; Carnera, 263¼. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

June 13, 1935âJim Braddock defeated Max Baer on points, Long Island City, 15 rounds. Baer, 209½, Braddock, 193¾. Referee, Jack McAvoy.

June 22, 1937âJoe Louis knocked out Jim Braddock, Chicago, Ill., 8 rounds. Louis, 197¼; Braddock, 197. Referee, Tommy Thomas.

Aug. 30, 1937âJoe Louis defeated Tommy Farr on points, New York City, 15 rounds, Louis, 197; Farr, 204¼. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Feb. 23, 1938âJoe Louis knocked out Nathan Mann, New York City, 3 rounds. Louis, 200; Mann, 193½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

April 1, 1938âJoe Louis knocked out Harry Thomas, Chicago, Ill., 5 rounds. Louis, 202½; Thomas, 196. Referee, Dave Miller.

April 1, 1938âJoe Louis knocked out Harry Thomas, Chicago, Ill., 5 rounds. Louis 202½; Thomas, 196. Referee, Dave Miller.

June 22, 1938âJoe Louis knocked out Max Schmeling, New York City, 1 round. Louis, 198¾; Schmeling, 193. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Jan. 25, 1939âJoe Louis knocked out John Henry Lewis, New York City, 1 round. Louis, 200¼; Lewis, 180¾. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

April 17, 1939âJoe Louis knocked out Jack Roper, Los Angeles, Calif., 1 round. Louis, 201¼; Roper, 204¾. Referee, George Blake.

June 28, 1939âJoe Louis knocked out Tony Galento, New York City, 4 rounds. Louis, 200¾; Galento, 233¾. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Sept. 20, 1939âJoe Louis knocked out Bob Pastor at Detroit, Mich., 11 rounds. Louis, 200; Pastor, 183. Referee, Sam Hennessey.

Feb. 9, 1940âJoe Louis defeated Arturo Godoy on points, New York City, 15 rounds. Louis, 203; Godoy, 202. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

March 29, 1940âJoe Louis knocked out Johnny Paychek, New York City, 2 rounds. Louis, 200½; Paychek, 187½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

June 20, 1940âJoe Louis knocked out Arturo Godoy, New York City, 8 rounds. Louis, 199; Godoy, 201½. Referee, Billy Cavanaugh.

Dec. 16, 1940âJoe Louis knocked out Al McCoy, Boston, Mass., 6 rounds. Louis, 202¼; McCoy, 180¾. Referee, Johnny Martin.

Jan. 31, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Red Burman, New York City, 5 rounds. Louis 202½; Burman, 188. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Feb. 17, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Gus Dorazio, Philadelphia, Pa., 2 rounds. Louis, 203½; Dorazio, 193½. Referee, Irvin Kutcher.

March 21, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Abe Simon, Detroit, Mich., 13 rounds. Louis, 202; Simon, 254½. Referee, Sam Hennessey.

April 8, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Tony Musto, St. Louis, Mo., 9 rounds. Louis, 203¼; Musto, 190½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

May 23, 1941âJoe Louis won on disqualification from Buddy Baer, Washington, D. C., 7 rounds. Louis, 201¾; Baer, 237½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

June 18, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Billy Conn, New York City, 13 rounds. Louis, 199½; Conn, 174. Referee, Eddie Joseph.

Sept. 29, 1941âJoe Louis knocked out Lou Nova, New York City, 6 rounds. Louis, 202¼; Nova, 202½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Jan. 9, 1942âJoe Louis knocked out Buddy Baer, in Naval Relief Fund bout, New York City, 1 round. Donated Purse to Naval Relief Fund. Louis, 206½; Baer, 250. Referee, Frank Fullam.

March 27, 1942âJoe Louis knocked out Abe Simon in Army Relief Fund bout, New York City, 6 rounds. Donated Purse to Army Relief Fund. Louis, 207½; Simon, 255¼. Referee, Eddie Joseph.

June 19, 1946âJoe Louis knocked out Billy Conn, New York City, 8 rounds. Louis, 207; Conn, 182. Referee, Eddie Joseph.

Sept. 18, 1946âJoe Louis Knocked out Tami Mauriello, New York City, 1 round. Louis, 211¼; Mauriello, 198½. Referee, Arthur Donovan.

Dec. 5, 1947âJoe Louis defeated Jersey Joe Walcott on points, New York City, 15 rounds. Louis, 211; Walcott, 194½. Referee, Ruby Goldstein. Split decision, Referee voted for Walcott, Judges voted for Louis.

June 25, 1948âJoe Louis knocked out Jersey Joe Walcott, New York City, 11 rounds. Louis, 213½; Walcott, 194¾. Referee, Frank Fullam.

On March 1, 1949, Joe Louis announced his retirement as undefeated heavyweight champion. Several tournaments were held to produce a successor.

June 22, 1949âEzzard Charles defeated Jersey Joe Walcott on points, Chicago, Ill., 15 rounds. Charles, 181¾; Walcott, 195½. Referee Dave Miller. This was for the N. B. A. title.

Aug. 10, 1949âEzzard Charles stopped Gus Lesnevich who was unable to come out for the eighth round, New York City. Charles, 180; Lesnevich, 182. Referee, Ruby Goldstein. It is recorded as a seven round knockout.

Oct. 14, 1949âEzzard Charles knocked out Pat Valentino, 8 rounds, San Francisco. Charles, 182; Valentino, 188½. Referee, Jack Downey. Clinched American heavyweight title.

Aug. 15, 1950âEzzard Charles defended N. B. A. title by knocking out Freddy Beshore in 14 rounds, Buffalo, N. Y. Referee, Barney Felix. Charles, 183¼; Beshore, 184½.

Sept. 27, 1950âEzzard Charles added New York State recognition to his N. B. A. claim by winning a 15 round decision from Joe Louis, Yankee Stadium, New York, N. Y. Charles, 184½; Louis, 218. Referee, Mark Conn.

Dec. 5, 1950âEzzard Charles knocked out Nick Barone, 11 rounds, Cincinnati. Charles, 185; Barone, 178½. Referee, Tommy Warndorf.

Jan. 12, 1951âEzzard Charles knocked out Lee Oma, 10 rounds, New York City. Charles, 185; Oma 193. Referee, Ruby Goldstein.