Come August, Come Freedom (12 page)

Read Come August, Come Freedom Online

Authors: Gigi Amateau

“Agreed, Dr. Foushee. He swaggers about the city and the countryside with the airs of a man born of a higher position,” Gervas Storrs observed.

Nor did the court hold Thomas Henry guiltless of Gabriel’s conduct. “Had young Prosser maintained proper control over his property,” Hezekiah Henley reasoned, “Johnson would have his ear, the pig his slop, and we would all be melting butter over our Sally Lunn bread.”

“They both love money above all else. Let them each feel this in the deepest possible way,” George Williamson recommended.

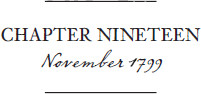

The gentlemen of the court of oyer and terminer sentenced Gabriel to jail and set his bail at one thousand dollars. The upstart planter and his proud bondman could reckon with each other over who would pay. With further punishment and high bond set, the court sent this message to Thomas Henry Prosser:

Get control of your property!

Thomas Henry may have desired wealth above all else, but the court was mistaken about Gabriel. He desired something other than money. Whosoever believed a hot brand, a jail term, and a high bond would sour Gabriel on liberty would soon discover that Gabriel was, indeed, born of a higher mind than the court had reckoned.

HE HOPED

Nan would wait. He hoped that when he returned, she would still marry him, as they had planned. For the month Gabriel sat in the damp, sour jail with no word from Thomas Henry and no way to get word to Nanny, this hope saw him through each day.

I’ll return to Brookfield, and I will marry Nanny.

For the first week of his sentence, he kept near the door of his cell, looking out, sure his old playmate would come. At two weeks, he let himself recline against the crumbling clay wall, still certain:

Thomas Henry will come.

At three weeks, Gabriel would have cursed himself for having had any faith in anyone, but every day Jacob Kent passed fish and greens and hard biscuits through the outer cell window. Gabriel’s teacher also brought news from the smithy — a source of sustenance. “The whole city is talking about you. Some are cautious. Worried about what might be brewing in the hearts of bondmen. Others say you are a hero. All agree you are a man to be feared,” Jacob told him.

“No reason for anyone to be afraid as long as I sit in this cell. Thomas Henry should be scared to his core for when I get out.” He didn’t bother to lower his voice.

Gabriel ate every bit of the food Jacob brought him and spared no morsel for the rats that shared his cell. For them, he left the watery porridge provided once daily by the jailer.

In early November, Thomas Henry finally appeared at the jail. “Come with me now. I have been summoned to court to guarantee your good behavior, including and especially toward Absalom Johnson,” he said to Gabriel.

Without glancing up from his spot by the cell door, Gabriel asked, “How can one man guarantee the acts of another?”

Thomas Henry ground his teeth together. “I know you better than anyone. Come with me now.”

“No. I know

you.

You are the same boy, lit with greed yet still not King Carter.” He would wait in jail forever before he groveled to Thomas Henry.

Thomas Henry pursed his lips and stiffened his jaw. “Gabriel, you’re coming home, and I must sacrifice a great deal for your release. It will cost me a thousand dollars to get you out of here and will cost you the same. The question is, how will you repay me?”

Gabriel turned toward the window, away from the cell door, away from Thomas Henry.

“We were friends once,” Thomas Henry said.

“I was a child,” Gabriel replied. He stroked the place on his forehead that marked the day Thomas Henry became a man. “You have grown up more barbaric than your father.”

“Gabriel, your father was a rascal, to be sure, but I don’t recall him gnawing off a man’s ear.” Thomas Henry lowered his voice so that only Gabriel could hear him. “I can tolerate your night walking to the colonel’s place, your impending marriage, which will yield me nothing, and even your sauntering here, there, and yon as you please. But this . . . this business with Johnson.” Thomas Henry’s temple swelled up and throbbed out in time with his heart. The young planter pressed his forehead against the bars. His voice cracked. “My peers whisper behind my back. My future father-in-law reprimanded me in public. The gentlemen of the court — my father’s friends —” Thomas Henry stopped talking when the jailer passed by.

Sometimes when Gabriel listened out the cell window, he heard the people talking nonsense — the boatmen, the washerwomen, the laborers of Richmond. Yet sometimes they spoke of a faraway island, convinced their freedom would soon come. And sometimes in the mornings, he heard them sing of Gabriel and glory and righteous peals of thunder. He needed out.

Gabriel turned back over and said to Thomas Henry, “I got five hundred hidden away. I can get you your money only if you get me out.” He stood up, and the usually unflappable rodents scattered away under the bed and back into the walls.

After the court released them, Thomas Henry sat ready to drive back to Brookfield in the same cart that had brought Gabriel to Richmond when he was a boy. The leather seat was now torn, its stuffing falling out, and the bay mare’s muzzle was turning white.

Gabriel bypassed Thomas Henry and headed east down Main Street, toward Jacob Kent’s forge, in the opposite direction from Brookfield.

The Prosser cart pulled up beside him. “Stop! Gabriel, get in here right now!” Thomas Henry shouted while he fought to bring Old Major’s bay mare to a halt. “Your pride and your insolence have cost you an awful lot lately.”

Gabriel kept walking.

“Do you want to end up back in jail?” Thomas Henry stood shouting in the gig.

He kept walking.

“Are you a common criminal, then?”

People around them stopped minding their business to watch the quarrel unfolding. A constable stepped up to Gabriel’s elbow. Still Gabriel kept walking.

“Get in,” Thomas Henry ordered.

He refused. “I’ll earn you better here in Richmond with Jacob Kent than in Caroline or Hanover. You want your money, you leave me be.” Gabriel eyed the constable, who stood ready to assist Thomas Henry, eager to subdue Gabriel. “Leave me be,

Master.

”

He did not look back again, even when Thomas Henry called after him, “Wait, Gabriel. We can work this out. Wait.”

I have waited too long for too little,

Gabriel thought. He neared Jacob’s forge and said out loud, to no one but himself, “My plan has changed.”

Again, Gabriel took his problem to the fire and the anvil.

GABRIEL HAD

seen Charles Quersey before and shod his stallion, but Jacob had always dealt with the Frenchman directly. This time, Quersey stopped in the smithy to have his pistol repaired and asked for Gabriel.

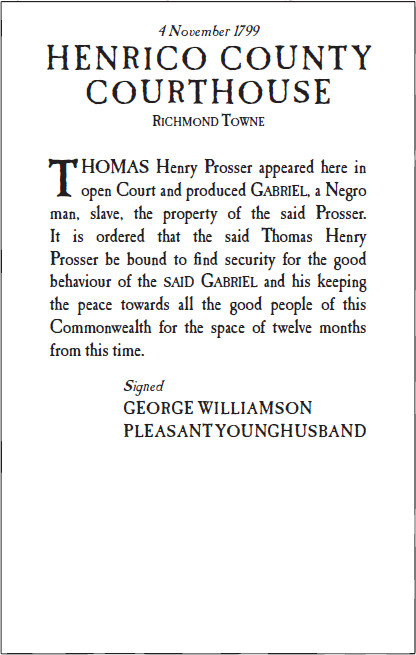

“I’ve heard about you,” Quersey said. “Are you able to read?” The man handed Gabriel a leaflet telling of America’s new alliance with Saint Domingue.

The leaflet was old, from the springtime, yet still Gabriel’s spirit was ripe to hear and ready to read how his own liberty was entwined with the now-free Caribbean island.

Gabriel touched the paper to his heart the way Ma used to touch her Bible, then handed the leaflet back to Quersey.

Quersey pressed the page back into Gabriel’s hand and also a small card bearing his name. “We are sons of liberty, Mister Gabriel. To truly be American, to be truly French, is to be free. I will not rest until every man is free. And you?” The French visitor left the forge without his gun.

Later, Gabriel asked Jacob, “Do you know Charles Quersey?”

“The Frenchman? Said to have been at Yorktown when ’Wallis surrendered. What’s your interest in him?”

Gabriel thought first to fib, but Jacob had never given him reason to run or hide or be anything but a truehearted man. He showed the newsprint to his teacher.

While Jacob read the leaflet, Gabriel watched him and waited for his teacher to look up. “I desire liberty for all the people, too,” Gabriel told Jacob. He waited to see, on this day, what kind of patriot Jacob Kent would show himself to be. “Now. Jacob, I want freedom now, not tomorrow or in one year or ten years or one hundred. Right now.”

Jacob spoke softly, almost to himself. “You were a boy when you came here, wearing those damned fancy clothes that belonged to someone else and those small shoes that pinched up your feet. Not the casings of a smithy, eh? No, you were not yet the strapping, gifted smith standing here. But on the afternoon when we first met, I knew who you were.” He touched Gabriel’s temple. “You are your father’s son, Gabriel. Privileged men’s notions of a convenient liberty could never fool you or your father. And, Just-Gabriel, you are a man now.” Holding the paper, Jacob’s hands trembled. “Will you agree that your old teacher has treated you fairly?”

Gabriel took the aged, familiar face in his hands.

I could never hurt you, Jacob,

Gabriel thought, then he tried to explain. “Teacher, I was going to marry Nan. I planned to buy her freedom and then mine, but Johnson threatened to harm her. There is no law to protect my woman from such a villain. I am a man, Jacob. Nanny’s man. What was I supposed to do?” Gabriel asked. “What am I supposed to do right now?”