Colossus (28 page)

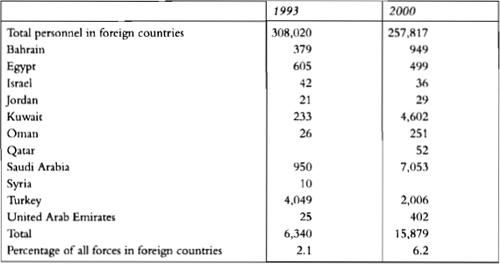

In many ways, the first Gulf War had greater consequences outside Iraq than inside it. Even after the war had been won, U.S. forces were not wholly withdrawn from the Middle East. On the contrary, during the 1990s the number stationed there tended to increase, as table 5 shows, from just over six thousand in 1993 to sixteen thousand by 2000. As a proportion of American forces stationed abroad, this represented a tripling of the U.S. military commitment to the region. Especially remarkable was the rising number of American personnel stationed in Saudi Arabia, temporary “tenants” of the royal dynasty that happened to be accompanied by between one hundred and two hundred warplanes.

17

These figures understate the extent of the American presence because they do not take account of the number of U.S. naval vessels deployed in and around the gulf. Nor do they capture another aspect of the growing Saudi military dependency: between August 1990 and December 1992 the Saudi regime placed orders worth more than twenty-five billion dollars with U.S. armaments manufacturers. In effect, the Arabian political system, with its exceptionally low military participation rate, made Riyadh dependent for its security on American manpower and firepower.

18

As we have seen, however, this only served to fuel the resentment of the radical Islamist movement inside and outside Saudi Arabia. As early as 1991 Saudi clerics, including Safar al-Hawali, an authority often cited by Osama bin Laden, were denouncing “a larger Western design to dominate the whole Arab and Muslim world.” Disgusted by the Saudi authorities’ reliance on American protection (they had declined his offer to lead an Afghan-style guer

rilla force against Saddam), bin Laden left Saudi Arabia in April 1991, traveling via Pakistan and Afghanistan to al Qa’eda’s new base in Sudan.

19

The fifth and final feature of the first Gulf War also had little to do with Iraq. This was what might be described as the marginalization of Israel. The Bush administration took the view that Israel should not serve as a center of military operations against Iraq—not even for supply, storage or medical purposes.

20

When Saddam fired Scud missiles at Tel Aviv, in an effort to cast himself as the archenemy of Zionism, the Americans worked energetically to prevent any Israeli retaliation. Moreover, in the wake of Desert Storm, Bush sought to apply pressure on Israel, in the hope of breaking the deadlock in the negotiations over the Palestinian question. In doing so, he reasserted the American conviction that any peace “must be grounded in the United Nations Security Council resolutions 242 and 338 and the principle of territory for peace.”

21

Two months later Secretary of State James Baker remarked pointedly that he knew of no “bigger obstacle to peace than the settlement activity that continues not only unabated but at an enhanced pace.” American loan guarantees worth ten billion dollars were allowed to lapse when the Israelis refused to accept conditions the United States attached to them.

22

After 1991 American aid to Israel was effectively frozen and in real terms declined. By 1999, as a proportion of Israeli gross national income, it was down to a third of its 1992 level.

TABLE 5. AMERICAN MILITARY PERSONNEL ON ACTIVE DUTY

IN THE MIDDLE EAST: 1993 AND 2000

Source:

Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1995

and

2002

.

NEVER SAY “NEVER AGAIN”

Bush the Elder could scarcely have been more rigorous in his commitment to the idea of a “new world order” under the aegis of the United Nations Security Council. Iraq was expelled and then contained according to the letter of its resolutions; Israel was to be forced to make peace with the Palestinians on the same basis. Yet events that were already unfolding by the time Bush left office in January 1993 were to force his successor to reexamine—albeit reluctantly and hesitantly—American attitudes toward the UN.

One of the time bombs Bush bequeathed to Clinton was the American involvement in the Somali civil war. At least five distinct military factions had been engaged in an escalating struggle for control of the country for most of the 1980s, but it was not until the end of 1992, with famine looming, that the United States became involved. Once again it did so with a mandate from the UN Security Council (resolution 794); a joint army, marine and navy task force was sent not to end the fighting but simply to facilitate the delivery of aid to the areas of greatest need. One of the new president’s earliest foreign policy acts was to wind this force down, from twenty-six thousand men to just five thousand. However, when gunmen loyal to warlord Mohammed Farah Aidid, leader of the grandly named United Somali Congress, murdered twenty-four UN soldiers from Pakistan, the Security Council issued a new resolution (837) authorizing his arrest. Dutifully, the United States responded by sending a detachment of Army Rangers supported by the elite Delta Force.

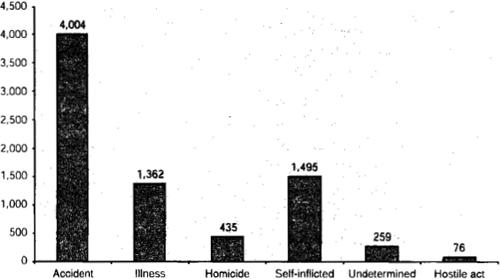

Like all Americans, William Jefferson Clinton had learned his lesson from the Vietnam War. But it was a different lesson from Colin Powell’s. Powell’s, as we have seen, was that American forces should never fight other than from a position of overwhelming strength, with limited goals that could be swiftly attained while commanding public support. Clinton’s was more simple. It was that presidents who presided over wars in which American soldiers died did not get reelected. The unspoken Clinton Doctrine was thus as simple and as radical as the Powell Doctrine: the United States should not engage in any military interventions that might endanger the lives of American service personnel. To this doctrine he was faithful throughout his eight years in office, as

figure 10

shows: during the Clinton

years, the chances of an American serviceman being killed by hostile action while on active duty were less than 1 in 160,000. He was six times more likely to be murdered by one of his comrades, nineteen times more likely to kill himself and fifty times more likely to die in an accident. Indeed, in 1999 a young American was almost as likely to be a victim of hostile fire if he stayed in high school than if he joined the army. Unfortunately for Clinton, almost the first military intervention he authorized resulted in a spectacular military debacle that left eighteen Americans dead. This was the now celebrated “Black Hawk Down” fiasco in Mogadishu.

According to Mark Bowden, it was not good luck but calculation that led the Somali forces to shoot down two of the American helicopters that had rashly been sent on a daylight mission to “snatch” Aidid and his lieutenants. “Every enemy advertises his weakness in the way he fights,” Bowden has written: “To Aideed’s fighters, the Rangers’ weakness was apparent. They were not willing to die…. To kill Rangers, you had to make them stand and fight. The answer was to bring down a helicopter. Part of the Americans’ false superiority, unwillingness to die, meant they

would do anything to protect each other, things that were courageous but also sometimes foolhardy.”

23

To read his account, based on interviews with survivors of the abortive raid, is to be impressed not only by the truth of this—indeed, by its understatement, since the Americans appear to have been willing to risk their lives to rescue even the bodies of their dead comrades

24

—but also by an unmentioned corollary, the Rangers’ tremendous readiness to slaughter Somalis indiscriminately. The worst aspect of the Black Hawk Down episode was not that eighteen American soldiers died; it was that at least as many and probably more unarmed Somali men, women and children were indiscriminately mowed down by panicking Rangers.

FIGURE 10

Deaths of U.S. Service Personnel on Active Duty by Manner of Death, 1993–2000

Source: U.S. Department of Defense.

Clinton’s response took a form that has been characteristic of many American interventions before and since. He increased the number of troops, but at the same time he specified a date for their departure, just six months later. The plan to capture Aidid was quietly abandoned. Indeed, he was flown in a U.S. transport plane to a peace conference in Ethiopia just a few weeks later.

25

The problem with this approach hardly needs to be spelled out: the certainty that American forces would soon be gone removed any incentive on the part of the Somali warlords to mend their ways. Something very similar happened in September 1994, when the Clinton administration—once again acting under a UNSC resolution (940)—sent twenty thousand troops to Haiti to restore the elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had been ousted by the military three years before. Six months later the United States handed over responsibility to a UN mission, leaving only a few hundred men on the island and allowing Aristide to resume the normal routine of Haitian politics: theft, murder, intimidation, corruption.

In ethnically homogeneous Haiti, where 95 percent of the population are the descendants of African slaves, there can never be such a thing as genocide; there can be only mass homicide. Yet genocide, meaning the murder of a tribe or people, loomed ever larger than plain murder in the course of the 1990s. The term is itself a neologism dating back to 1944, when it was coined by Raphael Lemkin in his book

Axis Rule in Occupied Europe

. Lemkin was a Polish-Jewish refugee from nazism, whose family was all but obliterated in the Holocaust (forty-nine of his relatives died, including his

parents; only his brother and his brother’s wife and children survived). It was his single-handed campaign that turned a made-up word into one of the foundations of postwar international law. By the end of 1948 it seemed that Lemkin had triumphed. Not only had the UN General Assembly unanimously passed a resolution condemning genocide in 1946, but by 1948 it had passed—again

nem con

—a Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

26

Yet there proved to be a nearly fatal flaw in Lemkin’s project. The country that had granted him asylum, the United States—in other words, the country best placed to do something to stop genocide, whether by economic pressure or military intervention—refused to ratify the convention. Indeed, it was not until 1985 that opposition in the Senate was finally overcome (in an attempt by the Reagan administration to repair the damage done by the president’s ill-judged visit to the Bitburg War Cemetery in West Germany, where forty-nine Waffen SS officers turned out to be buried). Hardbitten realists still argued that the UN convention ought not to be ratified since it would tend to enhance the standing of the International Court of Justice. Indeed, Senator Jesse Helms sought to water down the terms of ratification with a number of so-called reservations, understandings and declarations. Nevertheless, as the study and memorializing of the Holocaust came to occupy an ever more important place in American cultural life, such realism grew less respectable. Democratic and Republican presidents alike took their turns to insist that genocide must never be allowed to happen again. Thus Jimmy Carter in 1979: “We must forge an unshakable oath with all civilized people that never again will the world fail to act in time to prevent this terrible crime of genocide.” Thus Ronald Reagan in 1984: “Like you, I say in a forthright voice, ‘Never again!’ ” And thus Bill Clinton in 1993, opening the Holocaust Museum in Washington: “We must not permit that to happen again.” Unfortunately, “never again” turned out in the 1990s to mean “no more than once or twice a decade.”

There is no need here to detail the events that led to the disintegration of the multiethnic Yugoslav federation into twelve territorial fragments. The crucial point is that where this disintegration was violent—notably though not exclusively in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Krajina and Kosovo—

it posed a profound challenge to all those who had pledged never to permit another genocide (least of all in Europe). The deal struck between the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic and the Croatian leader Franjo Tudjman in March 1991 to partition Bosnia was always intended to lead to “cleansing of the ground” (

ciscenje terena

) of Muslims (hence “ethnic cleansing”); as Tudjman later remarked, there was intended to be “no Muslim part,” despite the fact that Muslims accounted for two-fifths of the population. From the moment the Bosnian Serbs proclaimed their own independent republic centered on Pale and began their attacks on Sarejevo (April 1992) the world was faced with an unmistakable case of genocide as defined in the UN convention.

27

What is more, although atrocities against civilians were perpetrated by all the three sides in the conflict, there was from an early stage evidence that most of the genocidal acts were the responsibility of the Serbian authorities in Pale and their masters in Belgrade. According to the State Department, only 8 percent of recorded atrocities during the war were the responsibility of Bosnian Muslims. And of all the crimes perpetrated during the war, none came close in its premeditated savagery to the massacre of more than seven thousand Bosnian Muslim men in Srebrenica by Serbian forces.