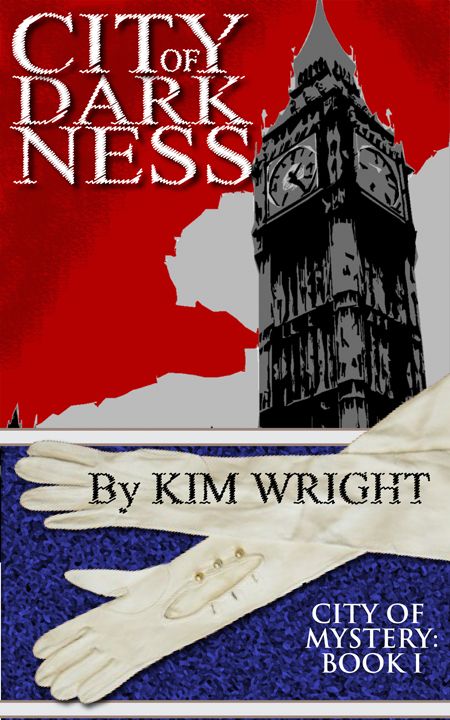

City of Darkness (City of Mystery)

Read City of Darkness (City of Mystery) Online

Authors: Kim Wright

City

of Darkness

City

of Mystery, Book 1

By

Kim Wright

To the

Brinkers Writing Group:

Ed, Paul,

Shontelle, Laura, Leigh, Mark, and Alan.

You read

every line, every paragraph, every draft.

PROLOGUE

August 7, 1888

2:25 AM

She saw the coins first. She always

did. A palm filled with silver and copper, extended from the shadows, held by

a man dressed in dark broadcloth. A man whose hands were clean.

This was a lucky turn, for Martha had

not secured a single gentleman all evening. She’d been roaming the pale gray

streets of Whitechapel since ten, looking for a last-minute sailor – even a

drunken or aged one, perhaps, for who could afford to be choosy with the hour

so late and the stomach so empty? She had smiled hopefully at each man she had

passed, and now, just as she had been on the verge of turning back, her

persistence had finally been rewarded.

She took the arm he offered her with

dignity, as if she were being led to the center of a ballroom. Martha

suggested the lodgings she shared with a half-dozen other girls, for they

weren’t far away, but the stranger declined, steering her instead toward one of

the innumerable alleys which flanked the waterfront. A gentleman, yes, but apparently

a gentleman in a hurry. The men who wore black broadcloth were often in a

hurry, Martha had noticed. They never seemed to need much preamble, rarely

expected her to open the front of her dress, didn’t request a name or a kiss. All

the better. She’d be at the pub within minutes, money in hand.

The man breathed something into her

ear and extended an arm around her waist. Liked taking it from the back, he

did, as was often the case with men who could afford wives and carriages and Mayfair

homes and perhaps even a bit of a conscience, the greatest middle-class luxury

of all. This was doubtless why they turned the faces of the whores away from

their own, why they arched their backs and concluded the matter so fast.

Martha didn’t mind. She’d always figured that whatever a gentleman pictured

when he closed his eyes was no business of hers. She let the man turn her.

She pressed both hands against the chipped brick wall and bent forward

obligingly, giving him access to what he’d paid for, her mind on the coins and

what they would buy. Beer and bread and stew, enough to fill her and perhaps a

friend, because Martha Tabram was a generous sort, never able to enjoy her own

supper while another went hungry, quick enough to give an extra twist or a moan

if the man had clearly gone lacking for a while. We’re all in this dark world

together, she figured. None of us saints.

But the man did not lift her skirts.

Instead, he murmured some words that Martha didn’t quite catch, and then she

felt a strange tug at her throat. He had begun to laugh, a low uneven chuckle.

Something was wrong.

She tried to scream, but all that

came out was a gurgle and, looking down, she saw the front of her gown turning

dark. Her lungs ached for a breath that was not there, and the weight of her

own body began to feel impossibly heavy. She raised her hand to her throat and

felt blood spurting out, running through her fingers like water from a pump. Red,

warm, and sticky.

He released her. She fell at his

feet. A light flared from above – was he striking a match? - and dimly

illuminated the cracks of the cobblestones. The pools of blood grew larger and

blacker around her until she could no longer see, but the other senses were

still with her and she could smell, yes, the sulfur of the stranger’s match and

the rich warm earthiness of his tobacco. It was the smell of her father and if

Martha could speak she would have said “Papa?” She would have asked her father

to pick her up and carry her away from this place, carry her like a child.

There was a sound, the clink of metal against stone. Once, then again and

again. Silver coins rained down into the street and the last emotion Martha Tabram

felt was surprise.

He was paying her.

CHAPTER ONE

September 9, 1888

2:14 PM

“Grandfather certainly picked an

inconvenient time to die,” Cecil muttered, gazing out the carriage window into

the shimmering heat of late summer. “The Wentworths are having their last ball

of the summer this Friday and I – “

“Will be home well before then,“

William said sharply. “How long can it take to read a will? It won’t be like

last week with the funeral arrangements and all those bloody scientists coming

in from all over the continent. This is just the family.”

Ah yes, just the family, Tom

Bainbridge thought, glancing from one of his brothers to the other. Just the

blessed family. Cecil and William had been dreaming of this day for years.

The one when William would at long last inherit, and although the family

carriage had been on the road to his grandfather’s estate for more than an hour,

William’s hands still gripped his cane with palpable tension. Tom’s mother and

his sister Leanna sat across from the three men, their faces obscured by their

mourning veils. Tom suspected there were many unspoken advantages to being

female, and one of them was the privilege of hiding one’s thoughts behind a

curtain of lace. Leanna had been weeping for a week, and she now sat slumped silently

against the shabby blue velvet of the carriage wall, as if she no longer had

the strength to even cry.

“Do you think you could manage to

show a little more respect?” their mother asked icily. She was the calmest of

the lot, perhaps because Leonard Bainbridge had been a father-in-law and not a

father, but more likely because the events of her life had taught Gwynette the

virtue of patience. She was the only one in the carriage who was traveling to

Rosemoral with neither grief nor hope. “Those scientists were Leonard’s

colleagues and they came from a great distance, at great inconvenience I would

imagine, to pay tribute to what he had done with his life.”

“Gad, mother, what was that?” Cecil

said, hitting Leanna’s knee as he shook a fly off his top hat. “Taking an

estate like Rosemoral and turning it into some sort of ridiculous laboratory

with ape skeletons lying about the place? The last time I was there he had a

full scale model of the….the digestive tract of a pig sitting on the French tea

cart the Prince of Wales gave Grandmama.”

“It was his tea cart, not yours,” Tom

snapped. “And if that’s truly the last thing you remember, it only shows how

rarely you visited him. He hasn’t done digestive experiments for years.”

The carriage gave a sudden lurch. It

had been some time since the family had been able to afford a matched team, so

for this long and heavy journey to Rosemoral, a short-legged pony had been

yoked to an aging horse, resulting in a remarkably uneven ride. Just one more

indignity in a series of indignities, Cecil thought, shifting towards his

younger brother, who’d nearly been unseated by this most recent bounce. “Naturally,

you and Leanna would defend anything Grandfather chose to do in his dotage,

even if it did involve displaying the remains of farm animals on priceless

antiques.”

“This is neither the time nor place

for this discussion,” Gwynette said, pulling aside her veil to reveal eyes of

such a supernaturally pale blue that they never failed to elicit comments from

anyone meeting her for the first time. Gwynette had been a beautiful woman

when she married Dale Bainbridge – the portrait in the upper hall attested to

that – but thirty subsequent years of struggle had left their mark. Her

beauty was not the kind to age well, and, since her husband had finally drank

himself to death five years earlier, her eyes had seemed to get lighter and

lighter, giving Tom the uneasy impression that his mother was fading away. “I

won’t have this squabbling,” she said. “Especially now, when we’re coming to

the end.” Whether she meant the end of the family’s genteel poverty or merely the

end this particularly unpleasant carriage ride wasn’t clear, but none of her children

requested further illumination, and for a moment the group fell into silence.

“A lovely speech, Mother,” Cecil finally

said, yawning and stretching out his legs. He was the only one who looked at

all like her, the only one to have inherited her unusual eyes. “But cast a

glance around. Bainbridge blood in every vein and yet here we sit in a broken

down carriage I’d be ashamed to haul hay in. It’s being pulled by a borrowed

pony and a horse that should have been shot a decade ago, and all this time we’ve

struggled, Grandfather has lived in an estate fit for a duke. You can’t

honestly say you aren’t relieved that the day is finally here when William is

going to inherit.”

“We’ve managed to support ourselves

at Winter Garden well enough.”

“Managed to hold on, isn’t that more

like it? Creditors are at the door every week and they’d have closed in by now

if they hadn’t known that grandfather would surely oblige us all by dying

sooner or later.”

“Enough, Cecil,”

Tom said. “Leanna’s here. Have you taken leave of

your senses?” The whole family turned their chins slightly toward the silent

figure in black, but the girl still didn’t move. She was normally the family

chatterbox, so her refusal to speak had the odd effect of dominating the

conversation.

Her grief is so damn ostentatious,

William thought, as Tom and Cecil fell into another pointless debate. Of

course, she loved Grandfather and probably spent more time at Rosemoral than

any of us, but all the same... Ever since the telegram had come

announcing that Leonard Bainbridge’s heart had at

long last given way, William had indulged a private fear. Was it possible his

grandfather would have ignored primogeniture and divided the estate among them

all? Such a stunt wouldn’t have been unprecedented in Bainbridge family

history, for Leonard’s own father had settled a startling amount on his

daughter Geraldine. Not just enough to allow the girl to marry well, which was

prudent, but enough to allow her to not marry at all, which was lunacy. The

woman had spent her life tearing about the world from India to Chile, throwing

family money into any number of crackpot causes, and Leonard – far from being

upset that his own inheritance was diluted – had always seemed amused by his

sister’s exploits. William knew his grandfather would leave Leanna money, and

undoubtedly funds would be set aside for shrewd baby Tom, who had paid the old

man the ultimate compliment of following his footsteps straight to medical

school. A share for Cecil on general principle, enough for his mother to make

the much-needed repairs to Winter Garden….

But he wasn’t liberal enough to cut

the estate into quarters, was he? The question had been tormenting William for

the past eight days. Estates passed to first born males for a logical reason, to

hold family fortunes intact rather than allow them to be frittered away across

generations, and on one hand, Leonard Bainbridge had been nothing if not

logical. He respected the traditions that had preserved Rosemoral for

centuries, ever since it had been granted to a Lancaster loyalist during the

War of the Roses, and he would not likely make any decisions that would put it

into jeopardy now. William loved the property too, and was prepared to devote

his life to being a fit custodian for the land. He and he alone understood the

smell of the dirt, the calm of the trees, the silence of the upper rooms, the

patina on the leather chairs in the library. Leonard must have known that

William was the one who would protect Rosemoral with his last breath.

But, on the other hand - and this is

what had kept William from a week of good sleep - Leonard had occasionally

looked up from his scientific experiments to express interest in the same sort

of political causes that consumed his sister. Socialism. Decolonization.

Even women’s rights, a subject William held to be on an equal par with

experiments on the digestive tracts of farm animals. William stared at the limp

form of his sister. Surely Leonard would not have left her a full share, knowing

that a twenty-year-old girl would likely take any inheritance she received into

a marriage and thus out of the family. Leanna or Rosemoral? His grandfather

loved them both. Which was he thinking of at the end?

“Besides,” Tom was saying to Cecil,

his voice rising to a pitch that pulled William from his thoughts. “You could

have sought some sort of profession other than the social circuit. And what of

William? He’s twenty-eight and hasn’t turned his hand to anything.”

“Professions aren’t for eldest sons,”

William said, relaxing his grip on his cane, and feeling suddenly sure of

himself. “Professions are for youngest sons, like yourself.”

Tom wasn’t going to let it go.

“Grandfather was an eldest son, and an heir, and he still did something useful

with his life.”