Citizen Emperor (95 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

In Spain, the demonization of Napoleon extended to his family and even to Godoy. Although there does not seem to have been an extensive use of Satanic imagery in that country, there were texts that were reasonably widespread.

85

The Spanish Catechism, published in 1808, associated Napoleon with the devil and considered the French to be heretics.

86

‘Who is the enemy of our happiness? – The Emperor of the French. Who is this man? – A villain, ambitious, the source of all evil and so on.’

87

It is impossible to know what impact this sort of primitive propaganda had on the people of Spain.

E. T. A. Hoffmann,

Die Exorcisten

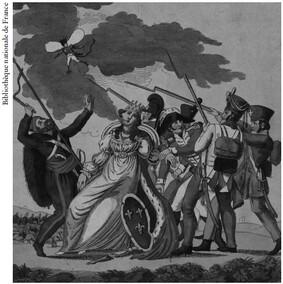

(The exorcists), no date but probably late 1813 or early 1814. Napoleon as the devil. In this engraving an Austrian, a Prussian, a Saxon and a Russian soldier (on the left with a knout) help exorcize France, represented by a woman, of Napoleon, portrayed as a little winged devil. An English soldier is taking her pulse. In the background, one can just make out Imperial Grenadiers fleeing, represented as pigs, wearing the traditional bearskin hat.

In Germany, popular engravings portrayed Napoleon as the Devil, or the son of the Devil. The essential characterization of Napoleon, not only among Germans but among other European peoples, was as a tyrant, impious, bloodthirsty, criminal, hypocritical and – possibly what worried Napoleon the most – illegitimate.

88

In 1811, the German poet Ernst Moritz Arndt wrote the following lines in his ‘Song of Revenge’:

Denn der Satan is gekommen

Er hat sich Fleisch und Bein genommen

Und will der Herr der Erde sein.

(For Satan has come

He has taken on flesh and bone

And wants to be lord of the Earth.)

89

The Prussian statesman Heinrich Friedrich Karl Freiherr vom Stein ranted about the ‘obscene, shameless and dissolute’ race that was the French, and declared that Paris should be razed to the ground. Ernst Moritz Arndt confessed, ‘I hate all Frenchmen without exception. In the name of God and my people, I teach my son this hatred. I will work all my life towards ensuring that hatred and contempt for this people finds deep roots in German hearts.’

90

Francophobia was rampant in the north of Germany and apparent in the pamphlet literature of the day.

91

Napoleon could not control the negative press in those countries beyond his reach, but even his own subjects considered that his immense appetite and ambition were leading to his destruction. The devastating consequences of his foreign policy in terms of human life undid any positive image Napoleonic propaganda may have created over the previous ten to fifteen years. In the words of Fontaine, ‘Blind ambition was his only guide.’

92

‘A Policy of Illusion’

About the time the Prussians declared war against France – that is, at the end of March and the beginning of April 1813 – Napoleon was putting the final touches to the new campaign he was about to embark upon. This time, he had set up a Regency Council – the lesson learnt from the Malet affair – to take charge of France in his absence. In order to do so, he had rapidly to bring about a change in the Constitution, pushed through the Senate at the beginning of February, so that a regency under Marie-Louise – aided by a council made up of Cambacérès, Joseph, Louis, Eugène, Murat, Talleyrand and Berthier – could rule if anything were to happen to him.

93

But he also worked long hours trying to put everything in order within the country, preparing his allies and getting the army ready for the campaign ahead.

94

It was a question of reasserting his hold on power before he went off campaigning again, but naming Marie-Louise regent was also a way of flattering Austria, of emphasizing the bond of blood that now existed between the two houses.

95

For a short time he seriously considered having a coronation ceremony for his wife, one that was initially fixed for 3 March and then postponed. The pope put paid to that idea. Napoleon arranged a meeting with him at Fontainebleau in the hope of mending broken bridges.

96

It did not go well. Pius, mentally and physically exhausted, initially signed a provisional agreement that was intended to serve as the basis of a future concordat, but then almost immediately retracted it. An opportunity to placate the Church and Catholics of the Empire had been missed.

Napoleon acted to shore up support at home. All military and civil functionaries were obliged to swear a new oath of loyalty to the King of Rome as heir to the Empire (the ceremony took place on 20 March). Marie-Louise was meant to play a prominent role; Napoleon made a great show of having her by his side in the months after his return and before his departure, attending meetings of the Council of State and all official functions. She always looked bored, and much like her aunt before her, Marie-Antoinette, was incapable of arousing much affection among the people of Paris. She officially took the title of ‘Regent’ on 30 March and swore an oath at the Elysée Palace. Marie-Louise was not, at this young age, able to stand up to much older, more experienced men – she was only twenty-two – but she performed her tasks in Napoleon’s absence well. However, she could never be anything more than a figurehead, who would ultimately have been subjected to the will of a dominant member of court.

Shortly before Napoleon left for Germany, he had an interview with the Austrian ambassador, Schwarzenberg. Schwarzenberg described Napoleon as someone who was less self-assured than he had been and afraid of losing his position; he even doubted whether he was the same man.

97

During the interview, Napoleon asked the ambassador for a corps of 100,000 men to fight alongside him. If Napoleon had any doubts at this stage about Austria’s loyalty, they were not expressed. He simply assumed that Austria would increase its army and co-ordinate its efforts with him. The French ambassador in Vienna transmitted Napoleon’s demand on 7 April. The response said to have come from Metternich, if true, is telling. He told the Prussian chancellor, Hardenberg, that the request was proof Napoleon was ‘committed to a policy of illusion’.

98

In fact, Napoleon entered the campaign with three illusions: that the Russo-Prussian alliance would disintegrate under a crushing blow; that he would be able to negotiate a separate peace with Russia; and that he could rely on Austria.

99

The Austrians had not at this stage decided to fight Napoleon, but they had certainly decided to allow the Russian army, now advancing towards the Elbe, free passage into Galicia and Bohemia. There is some reason to believe that given the state of public opinion in Vienna at the time, and the depth of the Austrian people’s hatred for Napoleon, it would have been difficult if not impossible for Metternich to side with France. When a rumour did the rounds in Vienna at the beginning of 1813 that Metternich had just signed an alliance with France to commit 300,000 men, it caused a stir the likes of which had not been seen since 1809.

100

Moreover, there were a number of Austrian officers who wanted to force the hand of their royal master in much the same way that the Prussian military had with Frederick William. Archduke John, for one, was working behind the scenes until, at the beginning of March 1813, the leaders of a conspiracy to assassinate Metternich were arrested by the Austrian secret police.

101

Napoleon finally left Saint-Cloud on 15 April at four in the morning to take charge of the army in the field. There is disagreement about just how effective a fighting force was the Grande Armée of 1813 – one historian asserts that the training of reserve troops was much better in the Russian than in the French army

102

– but it was certainly not the Grande Armée of 1805, let alone that of 1812.

103

What are commonly referred to as the ‘Marie-Louise’ boys from the class of 1813, 1814 and even 1815 were recognizable, according to General Marmont, by the fact that they were badly trained and lacked complete uniforms.

104

They do not appear to have been able to move as fast as recruits in previous years, as a result of which marches were kept short.

105

Orders were given to spare them so that they marched no more than sixteen kilometres a day.

106

This meant that Napoleon could no longer out-march or vigorously pursue the enemy. Nor were his troops well equipped.

107

By the time he left Paris, though, he had managed to bring together over 200,000 troops, on paper at least, including contingents from the Confederation of the Rhine, and between 450 and 600 cannon.

108

What he lacked, however, was cavalry, which meant that he could not reconnoitre and consequently could not know the enemy’s strength or movements with any certainty. At Erfurt ten days after leaving Paris, Napoleon looked worried by these developments.

109

But he did enjoy two slight advantages – unity of command and numerical superiority in troops.

Despite most central European monarchs holding their cards close to their chests, the Confederation of the Rhine was still a precious resource in men, money and matériel. During the Empire, an estimated 80,000 men from the Rhineland served in the French armies.

110

The call-up of men in Germany caused some unrest, and was notable too for the number of desertions.

111

Revolts were put down here and there. The closer the Russians got to the states of the Confederation, the more the loyalty of the German states seemed to waver.

112

Lützen and Bautzen

Napoleon took the field in the area of Dresden from where he planned to drive north into Prussia, and relieve the garrison holed up along the Oder and Vistula rivers.

113

On 30 April 1813, he led 120,000 men in the direction of Leipzig where he hoped to confront an allied army under General Wittgenstein. Napoleon arrived two days later to find that Ney was already engaged with Wittgenstein near a farming village called Lützen, twenty kilometres south-west of Leipzig.

The battlefield of Lützen is much as it was 200 years ago. Here, on 2 May, the two armies clashed.

114

It was not a planned battle, but one that developed as each side threw more and more troops into it. Napoleon, on his way to Leipzig, turned back surprised by the amount of cannon fire coming from Lützen, and was able to take control of the situation. He rallied the troops at some risk to his own personal safety,

115

and effectively carried out a flanking movement against the allied commander, Wittgenstein. The French won but were unable to carry through their victory for lack of cavalry. By the end of the day, the losses on both sides were higher than was normal for this kind of battle: around 20,000–22,000 French casualties and between 11,500 and 20,000 for the allies.

116

It was not much of a victory. The allies had learnt a few things over the years and were now much more formidable. Then Napoleon made an operational mistake, the first of many. He split his forces in two, sending 84,000 men north towards Berlin, while keeping the main army under his command.

117