Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (78 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

These allied malices twice conspired to bring about Photios's deposition as patriarch, first in 867 in favour of a restored Ignatios, and finally in 886, after which his various enemies did their best to make sure that his historical record would look discreditable. The Eastern Church nevertheless eventually decided that he should be celebrated as a saint (adroitly linking his name in liturgical acclamations with that of his eunuch rival), and there is good reason for such an expression of gratitude.

71

Photios's periods of patriarchal power coincided fruitfully with the coming of a succession of capable emperors who did much to restore the fortunes of the empire after two hundred years of miseries. They founded a dynasty which lasted for almost two centuries, the first to be so long sustained in the history of the entire Roman Empire, and known as Macedonians, from the birthplace of Basil, the first of the line. He was a courtier-soldier of relatively humble Armenian descent who schemed and murdered his way to the throne in 867, and who already in 863 had been responsible for a crushing victory over the Arabs. Emperor Basil I and his successors patiently brought relative stability and even expansion beyond their frontiers, and notably they turned their main attention west rather than east, even though they also ably blocked further Islamic encroachments on the empire. Their revival of Byzantine fortunes paralleled the imperial Church's moves to expand the bounds of Orthodox religious practice, Photios's lasting legacy. Orthodoxy owes its present cultural extent to his initiatives, which partly account for the dismal reputation that this patriarch long enjoyed in the Christian West.

Photios had not long been patriarch when the papal throne was taken by Nicholas I, whom we have met encouraging an imaginative rewriting of the past in order to assert the special authority of Rome (see pp. 351-2). Pope Nicholas was only too ready to make trouble for the incumbent patriarch by listening to the complaints of ex-Patriarch Ignatios. Photios's deep scholarship did not extend to any knowledge of Latin, and to a degree unusual among previous patriarchs, he was out of sympathy with the Western Church. There were good reasons for tension between the two outsize egos now presiding over the Church in Rome and Constantinople: at stake was the future Christian alignment of a vast swathe of southern central Europe in the Balkans and along the Adriatic coast (Illyricum and Great Moravia), an area long lost to the empire. Through it ran the ancient division between East and West first made by the Emperor Diocletian at the end of the third century (see p. 196). At a time when Frankish Latin Christianity was extending itself in northern and central Europe (see p. 349), the Byzantines were spurred to take a new interest in spreading their version of the faith as well as looking to extend their territories; there could be no better way of dealing with troublesome people on their frontiers such as the Bulgars than to convert them to Byzantine faith.

During the 850s and 860s a momentous event took place showing the possibilities and dangers of alternative conversions; it must have stimulated the imperial Church's moves beyond the frontiers. The entire people of a powerful and strategically important kingdom to the north-east of the Black Sea, the Khazars, were led by their khan to convert to Judaism, and no amount of persuasion by some of Photios's ablest advocates of Christianity could change the Khan's mind - maybe he remembered that, a century before, a Khazar princess had become the wife of the iconoclast Emperor Constantine V, and Byzantium's turn to iconophilia appealed less than Judaism's consistent ban on images. The Court language of the Khazars remained Hebrew and their mass conversion became one of the most significant (though often overlooked) moments in Jewish history.

72

Beyond political considerations, mission was a matter in which Photios took a passionate and personal interest. He is generally now reckoned to have written the preface of a new law code (

Epanagge

or 'Proclamation') issued by Emperor Basil I, which, in the course of its discussion of the relationship between imperial and ecclesiastical power in the empire, proclaimed that it was the duty of the patriarch to win over all unbelievers as well as to promote orthodoxy in belief.

73

Photios took advantage of Byzantine military success on the eastern frontiers to make repeated overtures to the estranged Miaphysite Church in Armenia, and it was not his fault that nothing ultimately came of his careful diplomacy and the remarkable degree of goodwill which he managed to engender.

74

Photius's relationship with Rome was much less conciliatory - indeed, one element in his overtures to the Armenians was to seek support in his conflicts with the Pope. Pope Nicholas was very ready to intervene on the Byzantine frontier, and various rulers in the region were not slow to exploit the resultant possibilities of playing off the Christians of West and East against each other. Chief among them was the deviously talented Khan Boris of the Bulgars (reigned 853-89), whose first move was to seek an alliance with his Frankish western neighbour King Louis the German, with an eye to threatening both the Byzantines and another people on Bulgarian frontiers, the Moravians. The Byzantines could not tolerate such an alliance, and with the aid of a large army, they ensured that in 863 the Khan accepted Christian baptism at the hands of Byzantine rather than Latin clergy and took the baptismal name of the Byzantine Emperor Michael himself.

75

Boris nevertheless continued to indulge in diplomatic bargaining with the bishops of Old and New Rome over the future jurisdiction of his new Bulgarian Church, producing a poisonous atmosphere which resurrected various long-standing issues of contention, such as the increasing Western use of the

Filioque

clause in the Nicene creed. Photios's furious comments on this matter have been described as 'a delayed-action bomb' in the simmering confrontation which culminated in the excommunication of 1054 (see p. 374), anticipated in 867 when Photios and Nicholas personally excommunicated each other over the Bulgarian question.

76

Once more Eastern and Western Churches were in schism.

The issue was not resolved when Nicholas died that same year, but soon Rome found itself desperate for help from the Byzantine emperor amid attacks by Islamic forces in southern Italy. The result was that two successive councils, meeting in Constantinople in 869 and 879, followed Khan Boris-Michael's eventual inclination to put himself and his Bulgarian Church under Byzantine patronage; he was encouraged by terms which suited him, granting him an archbishop of his own, over whom he could in practice exercise everyday control. The second council was a particular triumph for Photios, who was now restored to the patriarchate after the death of his rival and temporary supplanter, Ignatios. Bathing in the approval of the Emperor for all his work in extending the jurisdiction of the Church of Constantinople, Photios was acclaimed by the council as Oecumenical Patriarch, parallel in authority to the pope. This did not increase Rome's enthusiasm for the resolution of difficulties by decisions in councils, but the two councils had sealed the permanent extension of Christianity into one of the Balkans' most powerful and long-lasting monarchies.

Another success for Photios's missionary strategy developed among the Slavic peoples of Great Moravia, whose ruler Rastislav (or Rostislav, reigned 846-70) had the same sorts of ambitions and diplomatic skills as Boris of Bulgaria. The results were as momentous as they were complicated, and they continue to provoke controversy and tussles between Eastern and Western Christians over who owns their history. Modern-day Moravia is firmly within the Roman Catholic cultural sphere, like its neighbours in Austria, Bohemia, Croatia and Slovakia, and it is understandable that in the delicate state of central European relations over recent decades arguments have been made that Rastislav's 'Great Moravian' domains extended much further into south-eastern Europe, in lands which now have a primarily Orthodox tradition. The agents of the conversion were from Byzantium, two brothers born in the second most important city of the empire, Thessalonica (Thessaloniki), the port on the Aegean Sea. Growing up there, Constantine and Methodios would have known many Slavs, and Constantine in particular showed exceptional interest and ability in languages; he had been a student of Photios in the years before the scholar became patriarch, and Photios did not forget his talent.

77

The Patriarch used the brothers on that embassy to the Khan of the Khazars which sought to turn the Khan away from Judaism, but their lack of success did not prevent Photios launching them on a fresh expedition when Prince Rastislav asked for Byzantines to counter the influence of Frankish clergy operating in his territories.

78

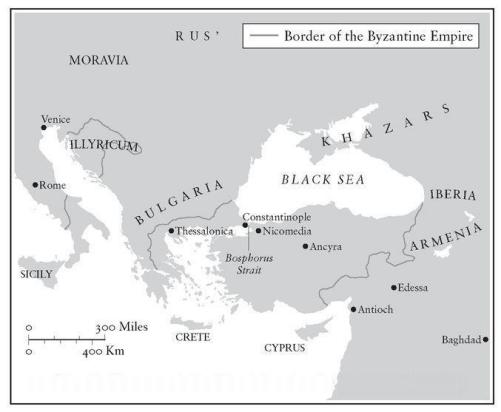

11. The Balkans and the Black Sea in the Time of Photios

The evidence suggests that even before Rastislav's request, the brothers had embarked on an enterprise of great significance for the future: they devised an alphabet in which Slav language usage could be accurately conveyed. It was given the name Glagolitic, from an Old Slav word for 'sound' or 'verb'. Constantine and Methodios did more than create a method of writing, because they also put a great deal of thought into creating an abstract vocabulary out of Greek words which could be used to express the concepts which lie behind Christianity. The Glagolitic alphabetic system is to say the least idiosyncratic, with only surreal resemblances to any other alphabetic form in existence, and when Bulgarians were looking for a way of writing their own version of Slavonic, it was an unappealing choice. They would be more familiar than the Moravians were with surviving antique inscriptions from the imperial past of their region, written in Greek. So it was probably in Bulgaria that, not long after the time of the two missionary brothers, another scholar devised a simpler alphabetic system, much more closely modelled on the uncial forms of the Greek alphabet.

79

It was named Cyrillic, in honour of Constantine, but in reference to the monastic name he adopted right at the end of his life, Cyril. That was an adroit piece of homage, which apart from the graceful tribute it embodied no doubt eased the new alphabet's acceptance in place of the holy pioneer's less user-friendly script.

Glagolitic did have a long-term survival, but mainly in relation to Slavonic liturgical texts. It was also adopted alongside Cyrillic for the Bulgarian liturgy by Khan Boris-Michael, who is likely to have seen the value of these innovative alphabets and the vernacular literature which they embodied as a way of keeping a convenient distance from both the Franks and also his eventual patrons in the Church of Constantinople. Both alphabets were specifically intended to promote the Christian faith. They and the Christianized Slavonic language which they represented were to be used not simply to produce translations of the Bible and of theologians from the earlier centuries of the Church, but with a much more innovative and controversial purpose. They made it possible to create a liturgy in the Slavonic language, translating it from the Greek rite of St John Chrysostom with which the brothers Constantine and Methodios were familiar. This was a direct challenge to the Frankish priests working in Moravia, who were leading their congregations in worship as they would do in their own territories, in Latin.

Although there was clearly East-West confrontation in the Moravian mission, there was a significant contrast with the Bulgarian situation, thanks to the diplomatic abilities of Constantine and Methodios. They were not themselves priests, and they deliberately set out to integrate their mission (albeit on their own terms) with the Church in Rome, seeking ordination for some of their followers from the Pope. While journeying to Rome, they attempted in Venice to defend their construction of a vernacular Slavonic liturgy, in a debate of which a rather partisan version survives in the

Life of Constantine

. Opponents objected that there were 'only three tongues worthy of praising God in the Scriptures, Hebrew, Greek and Latin', on the grounds that these were the three languages affixed to Christ's cross. 'Falls not God's rain upon all equally? And shines not the sun also upon all?' retorted Constantine.

80

Constantine's reception in Rome was much eased because he brought Pope Hadrian II a gift of fragments from the skeleton of Clement, one of the earliest of Hadrian's papal predecessors. With great foresight, Constantine had uncovered this lucky find during his otherwise unsuccessful time among the Khazars in the Black Sea region. Modern historians might spoil Constantine's pleasure by pointing out that the story of Pope Clement's exile to the Black Sea was actually a fifth-century confusion with the fate of another St Clement who probably really did die in the Black Sea region, but at the time Pope Hadrian was duly impressed and charmed into providing the necessary ordinations. A turning point in Church history was thus dependent on some wishful thinking and some misidentified bones.

81

Constantine spent his last months as the monk Cyril in Rome and when he died, in 869, he was buried appropriately in the already ancient Church of San Clemente - while equally appropriately and graciously, the last fragment of his body, otherwise destroyed during the Napoleonic occupation of Italy, was in the twentieth century given by Pope Paul VI for housing in a specially built Orthodox church in the saint's home city, Thessalonica or Thessaloniki.