Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (104 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

What they did was to woo the 'magistrates': the term which sixteenth-century Europe used to describe all its temporal leaders outside the Church hierarchy. These magistrates were indeed the superior powers referred to in Romans 13.1, just as the Roman emperor had been when Paul was writing. The leaders of the Church, the bishops, for the most part did not defect from the old organization, particularly those who were 'prince-bishops' of the Holy Roman Empire, temporal rulers as well as heads of their dioceses. Other magistrates might well be interested in a reformation which stressed theologies of obedience and good order, and also offered the chance to put the Church's wealth to new purposes. The first prince to come over was a major coup from a rather surprising quarter: the current Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, a Hohenzollern and cousin of Cardinal Albrecht of Mainz. The Teutonic Order had met increasing reverses in its long struggle with Poland-Lithuania (see pp. 516-17), and demoralized by major defeats in 1519-21, many of the Grand Master's knights had turned to evangelical religion, quitting the order. To save himself from ruin, he begged another cousin, King Sigismund I of Poland, to remodel the order's Polish territories in east Prussia into a secular fief of the Polish kingdom, with the Grand Master himself as its first hereditary duke; he did his first act of fealty to a gratified Sigismund in Cracow in April 1525. Naturally such a radical step as secularizing the territory of a religious order needed a formal act of rebellion against the old Church, and Albrecht of newly 'ducal' Prussia, who had already sounded out Luther in a face-to-face meeting in Wittenberg in late 1523, institutionalized this during summer 1525, creating the first evangelical princely Church in Europe.

19

Before Albrecht of Prussia, the initiatives in backing evangelical religious change had come from the self-confident towns and cities of the Holy Roman Empire, who enjoyed varying degrees of autonomy from emperor or princes. The first in the empire proper had been the Free City of Nuremberg, a great prize because the central legal and administrative institutions of the empire were sited there; the Nuremberg authorities allowed evangelical preaching in 1521. But a move of even greater significance came from a wealthy city in Switzerland, whose ties to the empire had been nominal since a victory of combined Swiss armies over Habsburg forces in 1499. Amid various cantons and free jurisdictions which made up the Swiss Confederacy, Zurich became home to another variety of evangelical Reformation which had little more than an indirect debt to Luther, and whose chief reformer, Huldrych Zwingli, created a rebellion against Rome with very different priorities. Certainly at the heart of it was a proclamation of the freedom of a Christian to receive salvation by faith through grace, and although Zwingli would never acknowledge his indebtedness to Luther on this point, it has always seemed rather more than coincidence that the Swiss Reformer should stumble independently on the same notion during the same European-wide crisis.

While Luther was a university lecturer who never formally had pastoral responsibilities for any congregation, Zwingli was a parish priest who, as an army chaplain, had seen the most extreme of pastoral experiences - that traumatic episode left him with a long-term commitment to Erasmus's arguments against war (contradicted at the last, as we will see). Parish ministry mattered to him deeply. A charismatic preacher at Zurich's chief collegiate church, the Grossmunster, he won a firm basis of support in the Zurich city council, which pioneered a Reformation steered by clerical minister and magistrate in close union. In Lent 1522, he publicly defended friends who had in his presence ostentatiously eaten a large sausage, thus defying Western Church discipline which laid down strict seasons and conditions for abstinence in food. Later that year, he and his clerical associates made an even more profound breach with half a millennium of Church authority than the inappropriate sausage by getting married. It took Martin Luther three years to follow suit.

Now not Rome but Zurich city council would decide Church law, using as their reference point the true sacred law laid down in scripture. From the early 1520s, Zwingli's Church was the city of Zurich, and the magistrates of Zurich could hold disputations to decide the nature of the Eucharist, just as they might make directions for navigation on Lake Zurich or make arrangements for sewage disposal. With their backing, Zwingli's clerical team, untrammelled by any major monastery, university theology faculty or local bishop, forged a distinctive pattern of evangelical belief with a great worldwide future. By the end of the sixteenth century, this Protestantism would be called Reformed, which crudely speaking meant all varieties of consciously non-Lutheran Protestantism. Often Reformed Protestantism has been called 'Calvinism', but the very fact that we are beginning to discuss it in relation to an earlier set of Reformers than John Calvin immediately reveals the problems inherent in that label, and suggests that it should be used sparingly.

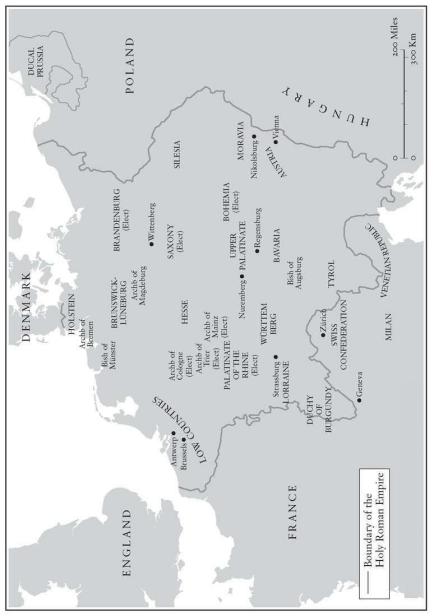

18. The Holy Roman Empire in 1530

The term 'Calvinist' began life, like so many religious labels, as an insult, and during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it persisted more among those abusing Reformed Protestants than among the Reformed themselves. There has never been any imposed uniformity among the Reformed family. Reformed Protestantism from the beginning differed from Luther's Reformation - much to his fury - in several key respects, principally its attitude to images, to law and to the Eucharist. The seeds of division were actually sown even before there was much contact between Wittenberg and Zurich, since, from 1521 onwards, Luther's independently minded colleague in Wittenberg University Andreas Bodenstein of Karlstadt had already started to push the logic of what Luther had said, in regard to these same questions. As Luther immediately failed to find common ground with Karlstadt, and eventually got him expelled from Wittenberg, it was not surprising that he failed to reach agreement with the reformers of the faraway Swiss city when he found that they were making similar statements.

It was Zwingli's friend Leo Jud, pastor of St Peter's across the river from the Grossmunster, who in a sermon of 1523 pointed out quite rightly that the Bible ordered the destruction of images in no less prominent a setting than the Ten Commandments. Jud (as that nickname 'Jew' indicated) was a distinguished Hebrew scholar: he noticed the significant oddity, forgotten by most of the Western Church, that there were two contrasting ways of numbering the Commandments, and that the system to which Augustine of Hippo had long ago given his authority conveniently downplayed the command against images. So Jud was reopening the question of images which had nearly brought the Byzantine Empire to ruin in the eighth and ninth centuries (see pp. 442-53), and which had been only briefly and partially reopened by John Wyclif and the avengers of Jan Hus a century before - Wyclif had noted that same numbering anomaly in the Ten Commandments. Now Zurichers started pulling down images from churches and from the roadside. This frequently involved disorder, and disorder has never enthused Swiss society. The city council took action: in October 1523 it arranged a further disputation, leading to the first official statement of doctrine produced anywhere in the Reformation. First, images were systematically removed from churches in June 1524 and then, in April 1525, the traditional form of the Mass itself was banned in the city. Until that latter moment, astonishingly, Zurich still remained in communion with its traditional ally the Pope, who had let politics blind him to the seriousness of what was happening there, and who never made any official condemnation of the man who was steering events in the city.

On the matter both of images and of the Eucharist, Luther was less inhibited than the Pope, and strongly and publicly disagreed with Zurich. Thanks to Karlstadt he had already faced image-smashing in Wittenberg in 1522, when he was alarmed enough by the disorder to hurry back from the Wartburg to preach against it, standing in the pulpit pointedly dressed in a brand-new monk's habit of his Augustinian Order.

20

After that bruising episode, Luther decided that the problem of sacred art was no problem at all. Once the most obviously absurd images had been removed in orderly fashion, destroying sacred art was actually a form of idolatry: it suggested that images had some power, and in fact they had none. What could be wrong with beautiful pictures of God's mother or of Christ hanging on the Cross? Luther used a battery of biblical arguments to offset the Ten Commandments; as early as 1520, when preparing teaching material on the Commandments, he showed his characteristic ability to play fast and loose with scripture by omitting all reference to the Commandment prohibiting images. He was certainly not going to adopt the 'Zurich' renumbering: the result, bizarrely, is that the Churches of western Europe still number the Ten Commandments differently, and the split is not between Roman Catholics and Protestants, but between on the one hand Roman Catholics and Lutherans, and on the other all the rest - including the Anglican Communion. Luther produced a formula to convey the usefulness of images: '

zum Ansehen, zum Zeugnis, zum Gedachtnis, zum Zeichen

' ('for recognition, for witness, for commemoration, for a sign'). After 1525, he rarely felt the need to enlarge on these points.

21

Great principles were at stake. Zwingli did not share Luther's negative conception of law, and because he so strongly identified Church and city in Zurich, he found the image of Zurich as Israel compelling. Israel needed law; law forbade idols. Where Luther had contrasted law (bad) and Gospel (good), Zurich now contrasted law (good) and idolatry (bad). Despite being a talented and enthusiastic musician, Zwingli even banned music in church, because its ability to seduce the senses was likely to prove a form of idolatry and an obstacle to worshipping God. Turned into a point of principle by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger, this ban lasted until 1598, when bored and frustrated Zurich congregations rose in rebellion against their ministers and successfully demanded the satisfaction of singing hymns or psalms in their services, since by then all other Reformed Churches allowed sacred music. The printers of Zurich had in fact been happily printing hymnals for those other churches for the previous fifty years.

22

Equally profound was the two men's disagreement about the Eucharist. Zwingli, a thoroughgoing humanist in his education and a deep admirer of Erasmus, emphasized the spirit against the flesh. A favourite biblical proof-text with him was Erasmus's watchword, John 6.63: 'The Spirit gives life, but the flesh is of no use' (see pp. 596-9). Luther, he thought, was being crudely literal-minded to flourish Christ's statement at the Last Supper, 'This is my body . . . this is my blood', as meaning that bread and wine in some sense became the body and blood of Christ. When Luther had jettisoned the idea of the Mass as sacrifice and the doctrine of transubstantiation, why could the obstinate Wittenberger not see that it was illogical to maintain any notion of physical presence in eucharistic bread and wine? Jesus Christ could hardly be on the communion table when Christians know that he is sitting at the right hand of God (this argument pioneered by Karlstadt may seem crass now, but it became a firm favourite with Reformed Christians). In any case, what was a sacrament? Zwingli, as a good humanist, considered the origins of the Latin word

sacramentum

, and discovered that the Latin Church had borrowed it from everyday life in the Roman army, where it had meant a soldier's oath. That struck a strong chord in Switzerland, where regular swearing of oaths was the foundational to a society whose strength came from mutual interdependence and local loyalty. It also resonated with that ancient Hebrew idea which has repeatedly sounded anew for Christians: covenant.

So the sacrament of Eucharist was not a magical talisman of Christ's body. It was a community pledge, expressing the believer's faith (and after all, had not Luther said a great deal about faith?). The Eucharist could indeed be a sacrifice, but one of faith and thankfulness by a Christian to God, a way of remembering what Jesus had done for humanity on the Cross, and all the Gospel promises which followed on from it in scripture. And what was true for the Eucharist must be true for the other biblical sacrament, baptism. This was a welcome for children into the Lord's family the Church; it did not involve magical washing away of sin. For Zwingli, therefore, the sacraments shifted in meaning from something which God did for humanity, to something which humanity did for God. Moreover, he saw sacraments as intimately linked with the shared life of a proud city. The Eucharist was the community meeting in love, baptism was the community extending a welcome. This nobly coherent vision of a better Israel, faithful to God's covenant, was a reformed version of Erasmus's ideal of how the world might be changed. It was utterly different from the raw paradoxes about the human condition, the searing, painful, often contradictory insights which constituted Luther's Gospel message.