Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States (4 page)

Read Chop Suey : A Cultural History of Chinese Food in the United States Online

Authors: Andrew Coe

The tribes on the east were called I. They had their hair unbound, and tattooed their bodies. Some of them ate their food without its being cooked. Those on the south were called Man. They tattooed their foreheads, and had their feet turned in towards each other. Some of them [also] ate their food without its being cooked. Those on the west were called Zung. They had their hair unbound and wore skins. Some of them did not eat grain-food. Those on the north were called Tî. They wore skins of animals and birds, and dwelt in caves. Some of them also did not eat grain-food.

13

Qing Dynasty accounts also often speak of alien peoples—including Europeans and Americans—and their customs in similarly belittling terms, describing their primitive taste in food, almost animal-like physical appearance, and so on.

Over the millennia, this streak of antiforeign bias in Chinese culture was balanced by intense curiosity about the outside world. From the Han Dynasty (206

BCE

–222

CE

) on, the Chinese did have regular contact with the rest of Asia. Chinese ambassador Zhang Qian roamed across Central Asia and even as far south as India, documenting the regional cultures and economies for his Han emperor. Regular trade between China, India, and the West began with the opening of the Silk Road by 100

BCE

(and likely earlier). Traffic in goods and ideas also traveled by sea, on oceangoing junks sailing to Japan, to many ports in Southeast Asia, and across the Indian Ocean to East Africa. Perhaps the most lasting result of those contacts was the dissemination between the second and seventh centuries

CE

of Buddhism, which originated in India. Over the centuries, the tribute network the Middle Kingdom established with its various vassal states became the official channel by which the finest products of foreign lands, from gems to foodstuffs, directly reached the emperor for his pleasure and

enjoyment. Between 1405 and 1433, the Yongle Emperor of the Ming Dynasty sent Admiral Zhen He’s fleet of three hundred ships on expeditions extending from Southeast Asia to Africa to assert Chinese power and expand the tribute system. In 1601, another Ming emperor hired the Italian Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci to serve as his court mathematician and cartographer. Ricci introduced western geometry and trigonometry and drafted accurate maps of the world showing latitude and longitude and the main continents. He could speak, read, and write Chinese, saw no contradiction between Catholic and Confucian beliefs, and converted many scholars and officials to Christianity. Even today, the Chinese admire Ricci for his deep knowledge of and respect for their culture.

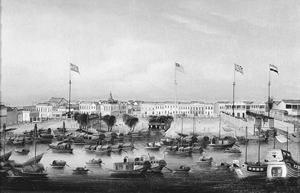

Figure 1.3. Large flags proclaim the western presence in the “factory” compound on the outskirts of Guangzhou. Until 1842, this was the only part of China where Europeans and Americans were allowed to live and trade.

By the time Ricci died, in 1610, Europeans were a constant presence at the edges of the Chinese empire. This incursion had begun in 1517 with the arrival of Portuguese traders, who soon acquired the rights to anchor at and then settle in Macau. They were followed by the Dutch and then, in the seventeenth century, the Spanish, French, English, and other European powers. The imperial government saw their presence as decidedly a mixed blessing. The European trade became highly profitable to the emperors, who took most of the profits directly into their coffers, restricting contacts with the European traders to the port of Guangzhou in order to protect their imperial monopoly, and for fear of foreign contagion. Imperial China was a highly organized yet delicately balanced machine—who knew what kind of cultural, economic, or political instability these strangers would bring? Official knowledge about Europe and its various peoples was designedly inadequate, because it was considered dangerous to learn more. Aside from the storerooms of the Forbidden City, the only place where Chinese could have seen European maps was Guangzhou. In the mid–eighteenth century, imperial courtiers drafted a massive, ten-volume encyclopedia, the

Illustrations of the Tribute-Bearing People of the Qing

(1761), that gave the official view of the outside world—one heavily influenced by the view of ancient texts like the

Shanhaijing

. All foreign peoples are defined by their level of allegiance, imaginary or not, toward civilization, that is, the Middle Kingdom. The authors do not bother to correctly locate England, France, Italy, Holland, Russia, or even the Atlantic Ocean. The inhabitants of the European countries are described as having “dazzling white” skin, “lofty” noses, and red hair. They favor tight clothes; their disposition is warlike; they esteem women more than men; and all they care about is trade. (In traditional China, since at least the days of Confucius,

merchants were relegated to the lowest rung of social status.) To imperial officials, the behavior of the Europeans resembled more that of dogs or sheep than that of civilized human beings. When the

Empress of China

—a European style of ship, with a crew who spoke the same language as the English—arrived in Guangzhou, local businessmen like Chouqua may have been curious about these people’s native land and glad to have new trading partners. To imperial officials, however, they were just more red-haired, white-skinned foreigners from the far-off zone of “cultureless savagery.”

At the end of the American War of Independence, Americans knew slightly more about China than the Chinese did about the United States. For about a half century, the American beverage of choice had been Chinese tea, which was shipped from Britain in crates marked with the stamp of the British East India Company. In 1773, dozens of citizens of Boston dressed as Mohawk Indians dumped crates of “Company” tea into Boston Harbor to protest unjust British duties on their favorite drink. Those Americans who could afford it drank their tea from delicate white cups of imported Chinese porcelain. Their image of China closely resembled the charming little scenes painted on the cups’ sides: stylized little blue willow trees, a river, and a bridge with one or two white-faced figures on it. George Washington was supposedly surprised to hear that the skin of Chinese was not bone-china white.

During the eighteenth century, the British East India Company enjoyed a monopoly on all trade with Asia. Merchants in the American colonies were forbidden to travel to China or deal directly with Chinese merchants. What little the colonists could learn about China was gleaned almost entirely from books and other accounts written by European travelers. Probably the most famous was the encyclopedic

General History of China

, by the French Jesuit priest Jean-Baptiste Du Halde. Both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson owned copies, as did Franklin’s Library Company of Philadelphia (in 1770) and the New York Society Library (in 1789). Du Halde never visited China, but he gathered his material directly from many Jesuit priests who had spent years there. His

General History

held up China’s government, law, and philosophy as models for emulation—Voltaire became a Sinophile after reading it. Those Americans lucky enough to peruse the tome could learn of the Great Wall and the emperor’s palace in Beijing, read the sayings of a sage named Confucius, and marvel at the rituals of a Chinese banquet where the most delicious dishes were “Stags Pizzles and Birds-Nests carefully prepared.”

14

Also widely disseminated was the anonymous work

The Chinese Traveller

(1772), supposedly based on the experiences of Jesuits and “other modern travellers.” A collection of stories of exotic customs and wide-eyed adventures in foreign lands, it reads more like

Gulliver’s Travels

than Du Halde’s measured account. Some of the information provided appears to have been picked up down at the London docks, including tips on where to find pleasure girls and warnings about trade: “the Chinese excel the Europeans in nothing more than the art of cheating.”

15

About Chinese food, the

Chinese Traveller

notes many oddities, including the use of chopsticks, the prevalence of rice, and the practice of chopping the food into little bits before bringing it to the table. What particularly interests the author is the wide variety of animals the Chinese ate: “they not only use the same kind of flesh, fish and fowl, that we do, but even horse flesh is esteemed proper food. Nor do they reckon dogs, cats, snakes, frogs, or indeed any kind of vermin, unwholesome diet.”

16

This description of the meats sold in Guangzhou delves deeper into that custom:

I was very much surprised at first, to see dogs, cats, rats, frogs, &c. in their market-places for sale. But I soon found that they made no scruple of eating any sort of meat, and have as good an appetite for that which died in a ditch, as that which was killed by a butcher. The dogs and cats were brought commonly alive in baskets, were mostly young and fat, and kept very clean. The rats, some of which are of a monstrous size, were very fat, and generally hung up with the skin upon them, upon nails at the posts of the market-place.

17

In nearly every western description of Chinese food from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this information is repeated: the Chinese dine on dogs, cats, and rats. Some of it comes from doubtful texts, like the

Chinese Traveller

, but in other texts the information has enough detail to give it the ring of truth. (And anyone who has visited modern Guangzhou’s markets can see that they still sell an incredible variety of live animals for food, including dogs and cats.) If readers of the time remembered anything about Chinese culinary habits, it was that they extended their eating habits to include beloved pets and filthy vermin.

Books like Du Halde’s

General History

and the

Chinese Traveller

were also popular because they contained large amounts of information about the country’s economic life: the principal products of China, the goods it most commonly imported, and the workings of its commerce. Americans did not read these sections idly, because the major source of their revenue was foreign trade. Merchants needed all the information they could find on the world outside their borders. After the War of Independence, Britain was still the dominant sea power, and its blockades kept American ships from much of Europe and the Caribbean. However, British power did not yet control the Pacific or the sea lanes leading to the world’s most populous nation. In the 1780s, the ports up and down the East Coast of the United States hummed with plans for voyages to China. The main promoter of these ventures was John Ledyard, an adventurer who had sailed with Captain Cook on his last voyage around the world. Ledyard proposed an enterprise to collect sea otter skins in the Pacific Northwest and sell them in Guangzhou for huge profits. When his backers realized that the scheme was too costly, they turned to what they knew from Du Halde’s

General History

. The Chinese were said to pay enormous prices for ginseng, which they used in their traditional medicine. Within months, the hold of the

Empress of China

was packed with ginseng root and heading east to China.

Figure 1.4. An engraving from

The Chinese Traveller

depicts men catching water fowl. According to the

Traveller,

ducks were trained to weed the rice fields and eat such pests as insects and frogs.

From 1784 to 1844, the yearly ritual of the China trade was nearly always the same. The American ships anchored at Whampoa at any time from August to October and unloaded their goods. The merchants took up residence in the American factory, with its “flowery flag” flying out front, and began the process of selling their wares to their Chinese counterparts. In the evenings, they retired to their quarters to eat sumptuous Western meals, washing the food down with copious amounts of imported alcohol, or traded social visits with the other foreign merchants. For recreation, they could promenade along the factory compound’s waterfront, compete in rowing races on the river, or stroll in the nearby Chinese gardens in the company of an interpreter. We know that life in the factories was claustrophobic but little else about what the Americans thought about China, because they were businessmen first and foremost. They left few records of their experiences there, particularly during the first decades of the trade. After their wares were sold, they purchased Chinese goods to sell back in the United States: tea, silk, porcelain, nankeen cloth, and sundry knickknacks with which they decorated their stateside homes. The Western ships usually sailed out of Whampoa in January. American merchants could then either sail home or spend the months until the next trading season in nearby Macau. With its picturesque setting, warm sea breezes, and large European colony, Macau was always considered a more pleasant place to stay than Guangzhou.