Chicken Soup for the Soul of America (4 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul of America Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

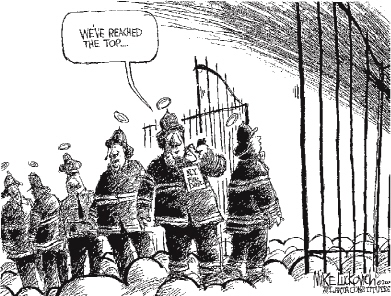

Reprinted with permission of Marshall Ramsey. ©2001 Copley News Service.

I

t was New York City's worst week.

But it was New York City's best week.

We have never been braver.

We have never been stronger.

Mayor Rudolph Giuliani

In the days before September 11, 2001, America was a little short on role models. Oh, we had basketball players, rock stars and millionaires, but there was a dearth of larger-than-life, genuine heroes. In those carefree, careless days, we had no one to show us how to

be:

how to be brave, how to be kind, how to be generous, how to be valiant.

Soldiers had come home from Vietnam, not war heroes but burned out and angry, and among them was oneâbedecked in medalsâwhose inner need for an outlet for the fury inside found its expression in the blaze of firefighting. I remember the first time I met Lieutenant Patrick Brown. It was in 1991, and by then he had become one of the most decorated firefighters in New York City. It was over dinner with a mutual friend in a restaurant where the staff knew and respected him. I was enchanted by his easy charm, the contrast between his ordinary-guy demeanor and his perceptive philosophy. And then, within days, I turned on CNN to see Patrick and another firefighter lying on their bellies on the roof of a building holding a one-inch rope in their bare hands, anchored to nothing, as another firefighter swung on the rope and rescued first one and then another frightened man from the window of a burning building. “The guy was going to jump if we didn't act right away, and there wasn't anything to tie the rope to,” Patrick explained, his hands abraded to shreds as he accepted another medal.

In 1999,

Time

magazine did a cover story on “Why We Take Risks” and featured Captain Patrick Brown among extreme skiers and race-car drivers. It was an odd juxtaposition from the start. Patrick's picture was a bit formal, but his quote was typical Pat. He said that in the F.D.N.Y. you were trained not to take “stupid risks.” It was never about money or thrills, he said, only for “the greater good.” When the article came out, he sent me a copy with a note that showed he was a little mystified at the honor . . . and the company.

As his legend grew, so did his spirit. He was relentless in his efforts to save those in need. It was said that if there were children or animals trapped in a burning building, Patrick was the one to send in. He had a special radar for the weakest among us, as if his heart were a magnet. The other firefighters admired, even loved him and called him “Paddy.” The women loved himâhe was so handsome. I thought he looked like a young Clark Gableâand we called him Patrick.

The more intensely he desired to help others, the more expansively he grew inside. He began to study yoga, saying it helped him find “the beauty of life again.” He even tried, to no avail, to get the other firefighters to practice with him. In an article in

USA Today,

his yoga teacher, Faith Fennessey, called him “an enlightened being.”

He trained for and received a black belt in karate, and then turned around and taught self-defense to the blind. He became incandescent, and yet if you had said so to his face, he would have shaken his head and changed the subject.

In 2001, I was writing a book with my partner, Judith Acosta, about words to say when every moment countsâwords that can mean the difference panic and calm, pain and comfort, life and death. And when I thought of life and death, I thought of Patrick. So I gave him a call. “What do you do, what do you say,” I asked, “when you encounter someone who's badly burned, maybe dying?”

He became thoughtful, almost shy, as he said that when things are at that terrifying pitch and lives are on the line, he tries to “spend a moment with the victim in silent meditation. Sometimes for just a few seconds, sometimes longer. It depends on the situation,” he said. “With some victims, I will put my hands on them and do a little meditation, breathe into it, think into the universe and into God. I try to connect with their spiritual natures, even if they're dying. It helps to keep me calm as much as I hope it helps them.”

On September 11, Patrick Brown arrived at the World Trade Center, focused with a clarity of vision that bore through smoke and flames. It is said that someone yelled to him, “Don't go in there, Paddy!” and it was reported that he answered, “Are you nuts? We've got a job to do!” I knew him better. Those weren't his words. So I was relieved when I talked with the men at Ladder 6 and they told a different story. One of the firefighters told me, “When they shouted to him not to go in, he said, âThere are

people

in there.'” Of course.

Another firefighter, who also spoke of how much they all admired Patrick, said, “I saw him enter the lobby and his eyes were

huge.

You know how he gets.” Yes. Drawn to battle. Drawn to serve. X-ray vision at the ready.

I visited Ladder 3, his company that had been devastated by the loss of twelve of their twenty-five brothers, and asked about Patrick. Lieutenant Steve Browne told me that, before he met Patrick, he had been a little worried about the new captain because he was such a legend. Surely he could be full of himself and difficult. And then Patrick walked in. “And he was so . . . modest,” Browne said. “He was just too good to be true. He always stood up for his men, no matter who he had to stand up to. You can't teach what he knew.” Another firefighter said of him, “He touched a lot of lives.”

I knew as a friend that he had never gotten over the deaths of some of his men in Vietnam. The medals never helped him sleep one bit better. By the time we met, he had also lost men on the job, and each loss tore at him like the eagle that tore out the liver of Prometheus (who, it happens, was punished for stealing fire from the gods to give to mankind). When Patrick went into the World Trade Center that fateful day, those who knew him agreed that he could not have lived through the grief of losing men one more time. If his men had died, and he had not, we believed, he would never have recovered.

And so, as we waited to hear the names of those lost in the tragedy, we hardly knew what to feel. A week later, the friend who had introduced us finally, against her own better judgment and wracked with fears, walked over to the firehouse to learn his fate. There sat Patrick's car, where he had left it before the disaster. It hadn't been moved. There was no one to move it. She turned away and went home. Hesitating again, she dialed his number. The phone rang and the messageâin his wonderful, gravelly Queens-accented voiceâanswered and, she told me, “I knew I was hearing a dead man.” And we both cried.

These days, since September 11, people have come to recognize that heroes aren't necessarily the richest, most popular people on the blockâthey are the most valiant, selfless people among us. A Halloween cover of the

New Yorker

magazine featured children dressed up as firefighters and police officers.

America has a new kind of role model now, one who has shown us how to

be.

After the evacuation order, as others were leaving the building, someone heard Patrick call out over the radio, “There's a working elevator on 44!” which means he had gotten that far up and was still and forever rescuing.

And then the apocalyptic whoosh.

I know it must be true that if you died with Patrick by your side, you died at peace. That was his mission. He was where he had to be, where he was needed, eyes wide, heart like a lamp, leading the way to heaven.

Judith Simon Prager

Reprinted by permission of Mike Luckovich and Creators Syndicate, Inc.

A Firefighter's Account

of the World Trade Center

W

e are shaken, but we are not defeated. We stare adversity in the eye and we move on.

Fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen

The South Tower of the World Trade Center has just collapsed. I am helping my friends at Ladder Company 16, and the firefighters have commandeered a crowded 67th Street cross-town bus. We go without stopping from Lexington Avenue to the staging center on Amsterdam. We don't talk much. Not one of the passengers complains.

At Amsterdam we board another bus. The quiet is broken by a lieutenant: “We'll see things today we shouldn't have to see, but listen up, we'll do it together. We'll be together, and we'll all come back together.” He opens a box of dust masks and gives two to each of us.

We walk down West Street and report to the chief in command. He stands ankle-deep in mud. His predecessor chief earlier in the day is already missing, along with the command center itself, which is somewhere beneath mountains of cracked concrete and bent steel caused by the second collapse of the North Tower.

Now several hundred firefighters are milling about. There is not much for us to do except pull a hose from one place to another as a pumper and ladder truck are repositioned. It is quiet: no sirens, no helicopters. Just the sound of two hoses watering a hotel on West Streetâthe six stories that remain. The low crackle of department radios fades into the air. The danger now is the burning forty-seven-story building before us. The command chief has taken the firefighters out.

I leave the hoses and trucks and walk through the World Financial Center. There has been a complete evacuation; I move through the hallways alone. It seems the building has been abandoned for decades, as there are inches of dust on the floors. The large and beautiful atrium with its palm trees is in ruins.

Outside, because of the pervasive gray dusting, I cannot read the street signs as I make my way back. There is a lone fire company down a narrow street wetting down a smoldering pile. The mountains of debris in every direction are fifty and sixty feet high, and it is only now that I realize the silence I notice is the silence of thousands of people buried around me.

On the West Street side, the chiefs begin to push us back toward the Hudson. Entire companies are unaccounted for. The department's elite rescue squads are not heard from. Just the week before, I talked with a group of Rescue 1 firefighters about the difficult requirements for joining these companies. I remember thinking then that these were truly unusual people, smart and thoughtful.

I know the captain of Rescue 1, Terry Hatten. He is universally loved and respected on the job. I think about Terry, and about Brian Hickey, the captain of Rescue 4, who just the month before survived the blast of the Astoria fire that killed three firefighters, including two of his men. He was working today.

I am pulling a heavy six-inch hose through the muck when I see Mike Carter, the vice-president of the firefighters union, on the hose just before me. He's a good friend, and we barely say hello to each other. I see Kevin Gallagher, the union president, who is looking for his missing firefighter son. Someone calls to me. It is Jimmy Boyle, the retired president of the union. “I can't find Michael,” he says. Michael Boyle was with Engine 33, and the whole company is missing. I can't say anything to Jimmy, but just throw my arms around him. The last thing I see is Kevin Gallagher kissing a firefighterâhis son.

Dennis Smith

Two Heroes for the Price of One

When I saw her on the

Good Morning America

show being interviewed by Charles Gibson the morning of December 11, she looked pretty much like the other widows I had seen since September 11: Her face still registered that awful sadness, that deeply etched worry for herself and her family left behind since the death of her husband, Harry Ramos. And, yes, there it was that bittersweet pride when others referred to her husband as a hero. But what struck me about Migdalia Ramos was something else. She was angry.

Migdalia Ramos was sitting next to the widow of the man that her husband had rushed back into the World Trade Center to try to save. Both of them died. Harry Ramos was the head trader at the May Davis Group, a small investment firm on the eighty-seventh floor of Tower One. All the other employees of May Davis got out. I understood immediately why Migdalia Ramos seemed angry. I felt anger too at the television program that had brought these two women together just for a good story. Didn't they see the pain here?

The television program centered on the coincidences between the two menâthings I thought were really irrelevantâlike the fact that Victor Wald, the man Harry Ramos had tried to save, had the same name as the best man at the Ramos's wedding or that both couples had a child named Alex. The only relevant link between these two women was the fact that they both had husbands who died just because they went to work that morning.