Chatham Dockyard (19 page)

Authors: Philip MacDougall

Still used in the manufacture of rope is this forming machine that dates to 1811 and was the product of Henry Maudslay, a leading engineer of the age.

A further factor that counted against the efficiency of Chatham’s existing dry docks was that they were constructed of timber rather than stone. Originally this had made a great deal of sense, it being cheaper and easier to build in timber. However, docks constructed of timber lacked durability, with those at Chatham, as already demonstrated, sometimes needing to be repaired at times that proved less than advantageous.

Although it would not have been impossible to completely modernise the dry docks at Chatham, any proposals were normally pushed aside on grounds of expense. The Chatham dry docks, as they stood, were of a very simple design, their shallowness partly resulting from the method used for their drainage. Unlike a series of dry docks that had been recently built at Portsmouth and Plymouth, those at Chatham had no attached pumping system. Instead, all four of Chatham’s dry docks relied upon gravity drainage, with water receding from these docks during the normal fall of tide. To provide the necessary additional depth, these docks would not only have to be rebuilt (preferably in stone) but the increased depth would have taken them to a point that was beneath the river Medway’s low tide level. As a result, a sophisticated pumping system would have to be introduced in order to remove large amounts of accumulated water. Rennie, aware of all this as he was, made a proposition that looked for a series of gradual improvements, rather than a dramatic and immediate wholesale rebuilding of the dry docks in the yard:

[As to] the shallowness of the dry docks, the plan I propose will not alter them; but as the docks are generally in a bad state, they must ere undergo a thorough repair, and when this is done, it will be the proper time to lay the floor of them sufficiently deep to take the largest ships to which their respective lengths are adapted; and such additional docks may be made as the demands of the public service may require, which perhaps may be to double the number of the existing docks.

1

The Admiralty concurred, agreeing that one dry dock should be built immediately with its construction placed under the overall supervision of Rennie. This new dock was to be of a much greater depth than the four existing docks and would be built of granite rather than timber. To be sited immediately to the north of the Old Single Dock, it would eventually be known as the No.3 Dock. At this point, some reference needs to be made to the overall numbering of docks, as the names originally used to distinguish each of the docks had ceased to have any relevance, leading to each being consecutively numbered. Thus, the original Double Dock (renamed the South Dock during the early eighteenth century) was now the No.1 Dock and the Old Single Dock was the No.2 Dock. In turn, the First and Second New Docks, situated further to the north and subsequently known as Nos 3 and 4 Docks would eventually be renumbered as docks 4 and 5, to make way for the new stone dock that was now to be built between the old Nos 2 and 3 Docks. For a time, this also meant that Chatham had five dry docks not four. This was only a temporary situation as, shortly after, the Old No.4 Dock (new No.5) was converted into a building slip. In turn, this also resulted in a consecutive renumbering of the slips, with the former dock having become No.3 Slip. From now on, therefore, all docks and slips will be referred to by the numbers that they had acquired following both the completion of Rennie’s new stone dock and the conversion of the No.5 Dock into a building slip.

Rennie provided a description of his proposed design for the new stone dock in a letter sent to the Navy Board in August 1815:

A view of the interior of the ropery, looking along the length of the laying floor.

The size of the dock is conformable to dimensions furnished me by the Surveyor of the Navy. The floor is proposed to be 4 feet under the level of low water of an ordinary spring tide, which according to Mr Parkin’s information rises 18½ feet, thus giving 22½ feet of depth at the high water of a spring tide, which I am informed will be sufficient not only to float a first rate but also admit of the proper sized blocks under her keel. At this time therefore there will be 4 feet of water to pump out of the dock at low water Spring Tides, and about 9 feet at neap tides, and for this purpose a steam engine will be required.

To this he added a series of estimates as regards its overall cost:

First, supposing the whole of the altars, floor and entrance to be made of Aberdeen granite. In which case the probable expense of the dock, admitting the whole to be set on piles, which from Mr Parkin’s borings I fear will be necessary, amount to £143,000. The steam engine, engine house, well and drain, amounts to £14,700; and working her for two years while these works are in hand £2,000.

2

Work on constructing the new dock was undertaken by John Usborne and Benson, a privately owned construction company, with John Rennie given access to the work at all times. The contract was signed on 16 February 1816 with payments made by the Navy Board at the rate of £1,000 for completion of each of a series of stipulated units. A separate pump house, this to accommodate a 50hp Boulton & Watt steam engine to be used in draining the dock, was also to be constructed. Situated immediately behind the new dock and on land formerly used for the storage of timber, this building was to be constructed by the dockyard’s own workforce. Originally it was hoped that the new dock would be available for use during the early part of 1819, or even earlier, but a number of delays, primarily due to the contractors under-ordering materials and scrimping on the number of artisans employed, meant that it was not to be finally completed until 1821 and resulting in a total cost that amounted to £182,286.

Rennie’s dry dock must be considered an important and significant feature of the yard, being the first to be built in the yard of a material other than timber. As such, it also paved the way for the complete rebuilding of three of the original docks, the No.5 Dock having been deemed better suited to conversion into a slip. The new No.3 Dock had a length of 225ft and a maximum width of 90ft. Internally it was characterised by stepped stone sides, these rising from the base of the floor to the ground level of the dockyard. Essential features of the dock, the steps were used both as a working area and as wedges to hold the shores resting against the sides of the otherwise unsupported vessel that stood within the dock. Divided into an upper and lower set, the top section of four steps was much steeper than a lower group of thirteen. Dividing the two sets was a broad central step that was primarily designed as a walkway. Access to the dock was by means of six sets of stone staircases, these positioned at the head, mid and aft sections of the dock. Finally, for the easy delivery of material to be used in the repair and building of ships, there were a number of stone slides (or ramps) which, at varying intervals, ran over the top of the stepped sides.

A particularly unusual feature demonstrated by the draft plan of the new dock was the use of a comparatively sophisticated entrance arrangement. As far as the existing docks were concerned, the entrance of a vessel was through a single pair of gates that were set either side of the slightly narrowing aft end of the dock. Held shut by a series of timber shores wedged between the gates and side walls of the dock, these gates were opened and closed through the application of manual power. The new dock dispensed with such a simple, if labour-intensive arrangement, introducing an entry neck that could be sealed at both ends. On the side of the neck closest to the dock was a pair of timber gates that could be opened and closed through the use of a capstan and chain device. The capstan was turned by only a small number of labourers, while the chains adhering to the gate held them firmly closed and overcame the necessity of using numerous timber shores for wedging purposes. According to Rennie’s draft plan, these gates spanned an entrance area of 57ft and opened out on to a special recess that prevented them becoming accidentally entangled with any vessel floated into the dock.

3

The river side of the short entry neck was sealed by a floating chest known as a caisson. Filled with water, a caisson would rest on the bed of the river, but once pumped free of water, could be floated and repositioned. Fixed into grooves that ran along the sides and bottom of the entry neck, it had the advantage of being completely removable and so allowed for the creation of a much wider entrance which was free of the additional need for a gate recess point. The use of a caisson was, during the second decade of the nineteenth century, a fairly novel innovation but, over time, completely

replaced the earlier entry gate system. That Rennie chose to use a caisson as the first of two entry seals results from a further drawback in the use of gates, this being that no matter how well they were sealed, water always leaked both through the central join and hinged sections. By introducing a short neck, any water gaining access past the caisson could be drained away before it reached the gates.

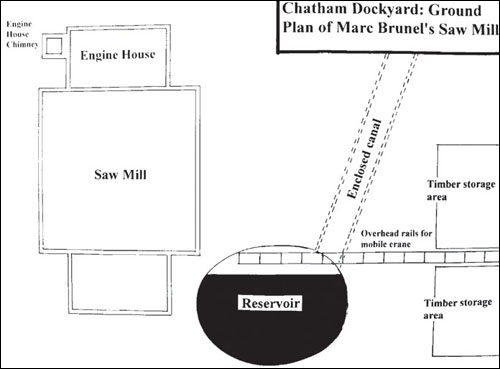

Ground plan of Brunel’s saw mill, which dates to 1814.

By way of his illness and eventual death in October 1821, Rennie was never to see the first stone dry dock at Chatham completed. Yet its continued existence within the historic dockyard serves as a suitable tribute to this great engineer and the frequent visits he made to Chatham to ensure its overall progress. Without his insistence that the dock was to be built entirely of stone and finished to the highest standards, it could not possibly have survived in virtually its original state for over 180 years. Indeed, even at the time of writing, the dock is still in use, having been engaged in the repair of naval warships up until 1984; it currently accommodates the nineteenth-century sloop, HMS

Gannet

, brought into the dockyard for permanent display.

4

Following completion of the new No.3 Dock, work commenced on lengthening and improving the Nos 1 and 2 Docks, with the work carried out from 1824 onwards. In both cases the design of these two docks, as reconstructed, was to be similar to that of Rennie’s earlier dock, in that they were also of granite, possessed stepped sides and were provided with a caisson at the entrance. The contractor, once again, was Usborne and Benson, with complaints again received about the tardiness of the work performed. In July 1825, for instance, Charles Cunningham, resident Commissioner at Chatham between 1823 and 1831, felt constrained to write to the Navy Board in the following terms:

Adverting to my former correspondence relative to the works carrying on in this yard at the Dock No.2, I think it proper to acquaint you that, not withstanding, there are only thirteen masons employed thereon. It appears by a report from the Master Shipwright that the quantity of stone in hand is not more than sufficient to keep them employed for about a fortnight but that the contractors stated to him on Saturday last another vessel was loading with that article and might be shortly expected. I suggest the propriety of the contractors being urged to send timely supplies of stone, in order that no impediment on that account, may take place in carrying on the works in question, with the few hands that are employed upon them.

5

To save costs, and ensure the docks were adequately pumped, the steam machinery built for the first new stone dock was also used for pumping the other docks.

An additional problem to which Rennie had alluded in his comments of 1814 was the deficiency of space for the storage of timber and other materials. As it stood, and according to Rennie, ‘the timber is obliged to be stacked wherever room can be found to lay it, by which the expense of teams [of horses] becomes very heavy’.

6

To his mind, the solution was for all matters relating to shipbuilding to be transferred to the Frindsbury side of the river, so providing additional storage space for timber dedicated to this task.

However, Rennie did not simply propose that the peninsula should become an adjunct to the existing yard but that it should be entirely incorporated into the existing complex. This would be achieved, so Rennie suggested, through the rerouting of the river by way of a channel that could be cut across the northern arm of the Frindsbury Peninsula. In turn, the existing channel, namely Chatham Reach, would be dammed and converted into a series of basins that would usefully serve the needs of ships being repaired and fitted out. In Rennie’s own words: