Challis - 05 - Blood Moon

Read Challis - 05 - Blood Moon Online

Authors: Garry Disher

| Blood Moon | |

| Challis [5] | |

| Garry Disher | |

| (2010) | |

| Rating: | ***** |

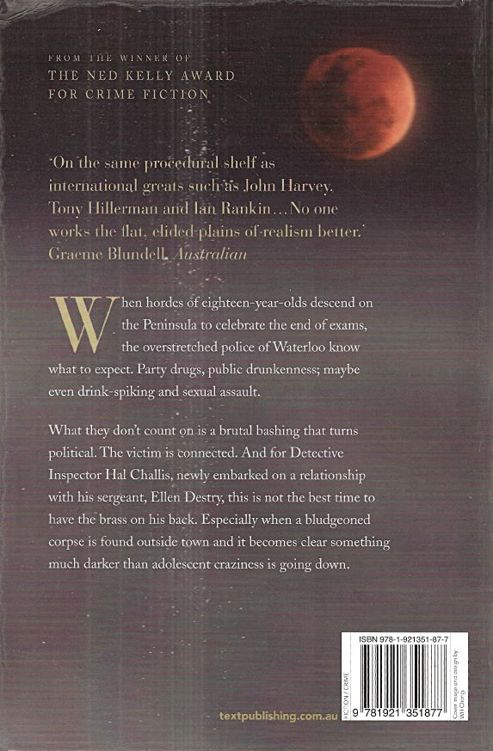

Two major crimes occupy Det. Insp. Hal Challis and his subordinate and now lover, Sgt. Ellen Destry, in this superior police procedural from Australian Disher, the fifth entry in the Ned Kelly Award–winning series (after 2007's

Chain of Evidence

). Challis and his team of Waterloo, Queensland, officers investigate the brutal assault on a private school chaplain as well as the murder of a public official in charge of enforcing compliance with land use regulations. Extra pressure for the first case's resolution comes from a prominent politician who already has an axe to grind with the police. That Challis's relationship with Destry violates police regulations complicates matters. Disher has a gift for terse description (e.g., Challis's boss wore the look of a man who'd been adored but only by his mother and long ago). While the deus ex machina solution to the official's murder may disappoint some, the personal interactions among Challis and his colleagues will quickly engage even newcomers.

Author tour. (Apr.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

“Excellent.”—Marilyn Stasio,

The New York Times Book Review

“Terrific, no-nonsense police procedurals.”—_The Seattle Times_

“A fine detective novel.”—_The Globe and Mail_ (Toronto)

The beating of a politically connected chaplain, a murdered planning official, a fundamentalist church, racist bloggers, and vacationing teenagers bedevil Inspector Hal Challis and his team as he and Ellen Destry try to keep their new romantic relationship from interfering with their work.

Garry Disher

is the author of over forty books for adults and children. A previous mystery in the Inspector Hal Challis series,

Chain of Evidence

, won the Ned Kelly Award for best Australian crime novel.

* * * *

Blood Moon

[Inspector Challis

05]

By Garry Disher

Scanned & Proofed By MadMaxAU

* * * *

1

On

a Tuesday morning in mid-November, late spring, the air outside the bedroom

window warm and pollinated, Adrian Wishart watched his wife urinate. He

happened to be sitting on the end of the bed, dressed, comb tracks in his hair,

tying his shoelaces. She was in the ensuite bathroom, perched naked on the loo,

wearing the long-distance stare that took her so far away from him. She didnt

know she was being observed. She tore off several metres of toilet paper,

patted herself dry, and as the water flushed it all away he came to the doorway

and said constrictedly, Were not made of money.

Ludmilla started and gave him a

hunted look. Sorry.

Folding in on herself, scarcely

moving, she opened the glass door to the shower stall. He rotated his wrist,

tapped his watch face. Im timing you.

Little things, but they cost money.

No one needed a long shower. No woman needed that much toilet paper. No need to

leave a light on when you go into another room. Why shop for groceries three or

four times a week when once would do?

Adrian Wishart watched his wife turn

her shoulders under the lancing water. It darkened her red hair and streamed

down her bodya body a little heavier-looking in the thighs and waist, he

thought. She was doing her daydreaming thing again, so he rapped on the glass

to wake her up. At once she began to work shampoo into her hair.

Wishart slipped out of the ensuite,

out of the bedroom, and made his way to the hallstand where she always stowed

her handbag. Purse, mobile phone, tampons, one toffeeso much for her

dietdiary and a parking receipt that he checked out pretty thoroughly: a

parking station in central Melbourne, maybe from when shed attended that

planning appeals tribunal yesterday. He unlocked her phone, scrolled through

calls made, stored text messages, names in her address book. Nothing caught his

eye. He was running out of time or hed have fired up her laptop and checked her

e-mails, too. Then again, she had a computer at work, and who knew what e-mails

she was getting there.

Her little silver Golf sat in the

carport, behind his Citroen. The odometer read 46,268, meaning that yesterday

shed driven almost 150 kiLornetres. He closed his eyes, working it out. The

round trip between home and her office in Waterloo was only seven kiLornetres.

That meant one thing: instead of driving a shire car up to the appeals tribunal

in the city yesterday, shed driven

her

car.

Their house was on a low hill above

the coastal town of Waterloo. He stared unseeingly across the town to Western

Port Bay and fumed: They were not made of money.

He checked his watch: shed been in

the shower for four minutes. He ran.

Ludmilla was towelling herself, skin

beaten pink by the water, slight but unmistakeable rolls of flesh dimpling here

and there as she flexed and twisted. She was letting herself go. He scooped the

scales out from under the bed, carried them through to the bathroom and snapped

his fingers: On you get.

She swallowed, draped her towel over

the heating rail, and stepped onto the scales. Just over 60 kilos. Two weeks

ago shed been 59.

Wishart burned inside, slow, deep

and consuming. Presently his voice came, a low, dangerous rasp: Youve put on

weight again. I dont like it.

She was like a rabbit in a

spotlight, still, silent and waiting for the bullet.

Have you been having business

lunches?

She shook her head mutely.

Youre getting fat.

She found her voice: Its just the

time of the month.

He said, At lunchtime on Friday I

called you repeatedly. No answer.

Ade, for goodness sake, I was in

Penzance Beach, meeting with the residents association.

He scowled at her. The Penzance

Beach residents association was a bunch of do-gooding retirees intent on

preserving an old house. Your car, or a work car?

Work car.

Good.

They breakfasted together; they did

everything together, at his insistence. She drove to work and he walked through

to the studio and arranged and rearranged his architectural pens, rulers and

drafting paper.

* * * *

2

Meanwhile

in an old farmhouse along a dirt road a few kiLornetres inland of Waterloo, Hal

Challis was saying, Uh oh.

What?

A flaw.

The detective inspector was propped

up on one elbow, playing with his sergeants hair, which was spread over the

pillow mostly, apart from the stray tendrils pasted to her damp neck, temples

and breasts.

I find that most unlikely, she

told him.

Ellen Destry was on her back, her

slender limbs splayed, contentedly. Challis continued to fiddle at her hair

with his free hand but his gaze was restless, taking in her eyes, lips and

lolling breasts. She looked drowsy, but not quite complete. She hadnt finished

with him yet, and that was fine by him. He freed his hand from the tangles and

ran the palm along her flank, across and over her stomach, down to where she

stirred, moist against his fingers.

What flaw? she said unsteadily.

Split ends.

Not in this hair, buster, she

said, punching him.

He rolled onto his back, pulling her

with him, and as he took one of her nipples between his lips the phone rang.

She said Leave it fiercely, but of course he couldnt, and Ellen knew that.

Because he was pinned beneath her, it was she who snatched up the receiver. Destry,

she said, in her clipped, sergeants voice.

Challis lay still, watching and

listening. Hes right here, she said, rolling off and handing him the phone.

Challis, he said.

It was the duty sergeant, reporting

a serious assault outside the Villanova Gardens on Trevally Street in Waterloo.

That apartment block opposite the yacht club, sir.

I know it.

Victims in a coma, the duty

sergeant went on. Name of Lachlan Roe.

Mugging? Aggravated burglary?

Dont know, sir. Uniforms took the

initial call. The nextdoor neighbour stepped outside to fetch her newspaper and

saw Mr Roe lying on his front lawn in a pool of blood.

Anyone from CIU there?

Sutton and Murphy.

Scobie Sutton and Pam Murphy were

detective constables on Challiss team. Crime scene officers? Ambulance?

The techs are on their way; the

ambulance has been and gone.

Challis, wondering why hed been

called, rolled his eyes at Ellen, who grinned and waggled her breasts. When he

reached out a hand she ducked away, rose from the bed and padded naked to the

window. He watched appreciatively. Cute ass, he drawled, covering the

receiver with his hand.

She did a little shimmy and opened

the curtains. The morning sun lit her, and the dust motes eddied, and the world

outside the window was vibrant: the chlorophyll, the spring flowers, the

parrots chasing and bobbing.

Challis returned to the phone. So

its all under control.

There was a pause. Finally the duty

sergeant said, It could get delicate. That meant one thing to Challis: the

victim was well known or had connections, and the result would be a headache to

the investigating officers. In what way?

The victims the chaplain at

Landseer.

The Landseer School, a boarding and

day school on the other side of the Peninsula. Not quite as old as Geelong

Grammar, Scotch College or PLC but just as costly and prestigious. Some wealthy

and powerful people sent their kids there, and Challis could picture the media

attention. He glanced at his bedside clock: 6:53. On my way, he said.

He replaced the handset and glanced

again at Ellen, who remained framed in the window. Struck by the particular

configuration of her waist and spine he crossed to her, pressed himself against

her bare backside.

She wriggled. Do we have time?

Certainly not.

* * * *

In

the shower afterwards, Challis outlined what he knew of the assault. The

Landseer School? said Ellen in dismay.

Exactly, Challis said. He watched

the water stream over her breasts, fascinated.

Keep your mind on the job, pal.

Fine, he said, Ill attend at the

assault. He stepped out and started towelling himself, watching as Ellen

wrapped one towel around her head and another around her body.

She gave him a complicated look. And

you want me in the office?

He nodded. If you could follow up

on that sexual assault from Saturday night...

This was delicate territory, there

was the faintest tension between them. He was her boss, they were living

together and it was too soon to know what the fallout would be. But it would

come, sooner or later. It was there in their minds as they dressed, Challis in

a suit today, guessing he would need to make an impression on the media or his boss

later. He knotted his tie, watching Ellen pull on tailored pants, low-heeled

shoes and a charcoal jacket over a vivid white T-shirt, the dark colours an

attractive contrast with the shirt and her pale skin and straw-coloured hair.

It was a familiar outfit to Challis, sensible work wear for a detective who

might sit at a desk one minute and be obliged to trudge through grass to view a

corpse the next, but she still managed to look spruce and intemperate. Her

clever, expressive face caught him watching. What?

Ill never tire of looking at you.

She went a little pink. Ditto.

They breakfasted at a rickety

camping table on the back verandah, where the sun reached them through a

tangled vine heavy with vigorous new growth. Realising that hed forgotten the

jam, Challis returned to the kitchen. He was pretty sure that one jar of quince

remained from the batch hed made back in April, but when he checked the

pantry, he saw that the spices, condiments and tubs of rice and pasta were on

the middle shelves, where hed traditionally stocked jam, honey and Vegemite.

These had been moved to a bottom shelf.

* * * *

3

Challis

and Destry left in separate cars, knowing the job would scatter them as the day

progressed. Ellens new Corolla was bright blue but streaked with dust and mud

like all of the locals cars. Challis followed in his unreliable Triumph. It

had held its secrets firmly for years, but now they were all coming out: rust

patches at the bottoms of the doors and in the footwells, oil leaks, corrosion,

a broken speedo cable, a slipping clutch, a whining differential. And the

shockers were shot: he hit a pothole in his driveway and felt the jarring

through the steering wheel.

He glanced across at his house as he

left the driveway. It was a pretty building, in the Californian-bungalow style,

dating from the Second World War. It sat naturally in the landscape on three

acres of grass, fruit trees and vague scrub, the only neighbours an orchardist

and a vigneron. He liked the seclusion; seclusion was his natural state. But

did it bother Ellen? Until her separation and divorce from Alan Destry shed

lived at Penzance Beach, in a small suburban house right next door to similar

houses, amid people who mowed their lawns, cooked on backyard barbecues,

knocked on the door to ask for a cup of sugar, sometimes played music too

loudly.