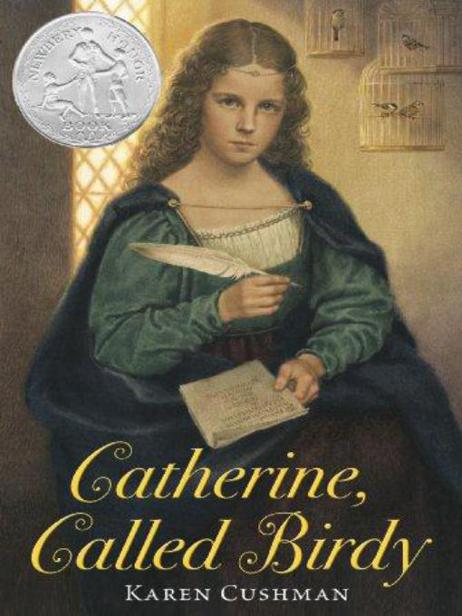

Catherine, Called Birdy

Read Catherine, Called Birdy Online

Authors: Karen Cushman

Karen Cushman

Table of Contents

C

LARION

B

OOKS

/

New York

Clarion Books

a Houghton Mifflin Company imprint

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003

Text copyright © 1994 by Karen Cushman

The text for this book was set in 12.5/15-point Centaur

Title type calligraphy by Iskra

All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions. Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10003.

Printed in the USA

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cushman, Karen.

Catherine, called Birdy / by Karen Cushman.

p. cm.

Summary: The thirteen-year-old daughter of an English country knight keeps a journal

in which she records the events of her life, particularly her longing for adventures beyond the

usual role of women and her efforts to avoid being married off.

ISBN 0-395-68186-3

[1. Middle Ages—Fiction. 2. England—Fiction. 3. Diaries—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.C962Kat 1994

[Fic]—dc20 93-23333

CIP

AC

QUF 20 19 18 17 16 15 14

SeptemberThis book is dedicated to Leah,

Danielle, Megan, Molly, Pamela, and Tama,

and to the imagination, hope, and tenacity of all young women

12

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

I am commanded to write an account of my days: I am bit by fleas and plagued by family. That is all there is to say.

13

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

My father must suffer from ale head this day, for he cracked me twice before dinner instead of once. I hope his angry liver bursts.

14

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Tangled my spinning again. Corpus bones, what a torture.

15

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Today the sun shone and the villagers sowed hay, gathered apples, and pulled fish from the stream. I, trapped inside, spent two hours embroidering a cloth for the church and three hours picking out my stitches after my mother saw it. I wish I were a villager.

16

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Spinning. Tangled.

17

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Untangled.

18

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

If my brother Edward thinks that writing this account of my days will help me grow less childish and more learned,

he

will have to write it. I will do this no longer. And I will not spin. And I will not eat. Less childish indeed.

19

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

I am delivered! My mother and I have made a bargain. I may forego spinning as long as I write this account for Edward. My mother is not much for writing but has it in her heart to please Edward, especially now he is gone to be a monk, and I would do worse things to escape the foolish boredom of spinning. So I will write.

What follows will be my book—the book of Catherine, called Little Bird or Birdy, daughter of Rollo and the lady Aislinn, sister to Thomas, Edward, and the abominable Robert, of the village of Stonebridge in the shire of Lincoln, in the country of England, in the hands of God. Begun this 19th day of September in the year of Our Lord 1290, the fourteenth year of my life. The skins are my father's, left over from the household accounts, and the ink also. The writing I learned of my brother Edward, but the words are my own.

Picked off twenty-nine fleas today.

20

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Today I chased a rat about the hall with a broom and set the broom afire, ruined my embroidery, threw it in the privy, ate too much for dinner, hid in the barn and sulked, teased the littlest kitchen boy until he cried, turned the mattresses, took

the linen outside for airing, hid from Morwenna and her endless chores, ate supper, brought in the forgotten linen now wet with dew, endured scolding and slapping from Morwenna, pinched Perkin, and went to bed. And having writ this, Edward, I feel no less childish or more learned than I was.

21

ST DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Something is astir. I can feel my father's eyes following me about the hall, regarding me as he would a new warhorse or a bull bought for breeding. I am surprised that he has not asked to examine my hooves.

And he asks me questions, the beast who never speaks to me except with the flat of his hand to my cheek or my rump.

This morning: "Exactly how old are you, daughter?"

This forenoon: "Have you all your teeth?"

"Is your breath sweet or foul?"

"Are you a good eater?"

"What color is your hair when it is clean?"

Before supper: "How are your sewing and your bowels and your conversation?"

What is brewing here?

Sometimes I miss my brothers, even the abominable Robert. With Robert and Thomas away in the king's service and Edward at his abbey, there are fewer people about for my father to bother, so he mostly fixes upon me.

22

ND DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

I am a prisoner to my needle again today, hemming linen in the solar with my mother and her women. This chamber is pleasant, large and sunny, with my mother and father's big bed on one side and, on the other, a window that looks out on the world I could be enjoying were I not in here sewing. I can see

across the yard, past the stables and privy and cowshed, to the river and the gatehouse, over the fields to the village beyond. Cottages line the dusty road leading to the church at the far end. Dogs and geese and children tumble in play while the villagers plough. Would I were tumbling—or even ploughing—with them.

Here in my prison my mother works and gossips with her women as if she didn't mind being chained to needle and spindle. My nurse Morwenna, now that I am near grown and not in need of her nursing, tortures me with complaints about the length of my stitches and the colors of my silk and the thumbprints on the altar cloth I am hemming.

If I had to be born a lady, why not a

rich

lady, so someone else could do the work and I could lie on a silken bed and listen to a beautiful minstrel sing while my servants hemmed? Instead I am the daughter of a country knight with but ten servants, seventy villagers, no minstrel, and acres of unhemmed linen. It grumbles my guts. I do not know what the sky is like today or whether the berries have ripened. Has Perkin's best goat dropped her kid yet? Did Wat the Farrier finally beat Sym at wrestling? I do not know. I am trapped here inside hemming.

Morwenna says it is the altar cloth for me. Corpus bones!

23

RD DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

There was a hanging in Riverford today. I am being punished for impudence again, so was not allowed to go. I am near fourteen and have never yet seen a hanging. My life is barren.

24

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

The stars and my family align to make my life black and miserable. My mother seeks to make me a fine lady—dumb, docile, and accomplished—so I must take lady-lessons and

keep my mouth closed. My brother Edward thinks even girls should not be ignorant, so he taught me to read holy books and to write, even though I would rather sit in an apple tree and wonder. Now my father, the toad, conspires to sell me like a cheese to some lack-wit seeking a wife.

What makes this clodpole suitor anxious to have me? I am no beauty, being sun-browned and gray-eyed, with poor eyesight and a stubborn disposition. My family holds but two small manors. We have plenty of cheese and apples but no silver or jewels or boundless acres to attract a suitor.

Corpus bones! He comes to dine with us in two days' time. I plan to cross my eyes and drool in my meat.

26

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Master Lack-Wit comes today, despite my mother's objections. Although she is wed to a knight of no significance, her fathers were kings in Britain long ago, she says. And my suitor is but a wool merchant from Great Yarmouth who aspires to be mayor and thinks a wife with noble relations, no matter how distant, will be an advantage.

My father bellowed, "Sweet Judas, lady, think you we can eat your royal ancestors or plant your family name? The man stinks of gold. If he will have her and pay well for the privilege, your daughter will be a wife."

When there is money involved, my father can be quite well spoken.

T

HE HOUR OF VESPERS, LATER THIS DAY:

My suitor has come and gone. The day was gray and drippy so I sat in the privy to watch him arrive. I thought it well to know my enemy.

Master Lack-Wit was of middle years and fashionably pale. He was also a mile high and bony as a herring, with gooseberry

eyes, chin like a hatchet, and tufts of orange hair sprouting from his head, his ears, and his nose. And all his ugliness came wrapped in glorious robes of samite and ermine that fell to big red leather boots. It put me in mind of the time I put my mother's velvet cap and veil on Perkin's granny's rooster.

Hanging on to the arm of Rhys from the stables, for the yard was slippery with rain and horse droppings and chicken dung, he greeted us: "Good fordood to you, by lord, and to you, Lady Aislidd. I ab hodored to bisit your bodest badder and beet the baided."

I thought first he spoke in some foreign tongue or a cipher designed to conceal a secret message, but it seems only that his nose was plugged. And it stayed plugged throughout his entire visit, while he breathed and chewed and chattered through his open mouth. Corpus bones! He troubled my stomach no little bit and I determined to rid us of him this very day.

I rubbed my nose until it shone red, blacked out my front teeth with soot, and dressed my hair with the mouse bones I found under the rushes in the hall. All through dinner, while he talked of his warehouses stuffed with greasy wool and the pleasures of the annual Yarmouth herring fair, I smiled my gap-tooth smile at him and wiggled my ears.

My father's crack still rings my head but Master Lack-Wit left without a betrothal.

27

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

Being imprisoned in the solar was none so bad this day, for I heard welcome gossip. My uncle George is coming home. Near twenty years ago he went crusading with Prince Edward. Edward came home to be king but George stayed, finding other lords to serve. My mother says he is brave and honorable. My father says he is woolly-witted. Morwenna, who

was nurse to my mother before me, just sighs and winks at me.

Since my uncle George has had experience with adventures, I am hoping that he can help me escape this life of hemming and mending and fishing for husbands. I would much prefer crusading, swinging my sword at heathens and sleeping under starry skies on the other end of the world.

I told all this to the cages of birds in my chamber and they listened quite politely. I began to keep birds in order to hear their chirping, but most often now they have to listen to mine.

28

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

,

Michaelmas Eve

Perkin says that in the village of Woodford near Lincoln a man has grown a cabbage that looks like the head of Saint Peter the Apostle. People are gathering from all over the shire to pray and wonder at it. My mother, of course, will not let me go. I had thought to ask Saint Peter to strengthen my eyes, for I know it unattractive to squint as I do. And to make my father forget this marriage business.

29

TH DAY OF

S

EPTEMBER

,

Michaelmas, Feast of the Archangel Michael

Last night the villagers lit the Michaelmas bonfires and set two cottages and a haystack afire. Cob the Smith and Beryl, John At-Wood's daughter, were in the haystack. They are scorched and sheepish but unhurt. They are also now betrothed.

Today is quarter-rent day. My greedy father is near muzzle-witted with glee from the geese, silver pennies, and wagonloads of manure our tenants pay him. He guzzles ale and slaps his belly, laughing as he gathers in the rents. I like to sit near the table where William the Steward keeps the record and listen to the villagers complain about my father as they pay. I have gotten all my good insults and best swear words that way.

Henry Newhouse always pays first, for at thirty acres his is the largest holding. Then come Thomas Baker, John Swann from the alehouse, Cob the Smith, Walter Mustard, and all the eighteen tenants down to Thomas Cotter and the widow Joan Proud, who hold no land but pay for their leaky cottages in turnips, onions, and goose grease.