Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World (27 page)

Read Catastrophe: An Investigation Into the Origins of the Modern World Online

Authors: David Keys

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Asian History, #Geology, #Geopolitics, #European History, #Science, #World History, #Retail, #Amazon.com, #History

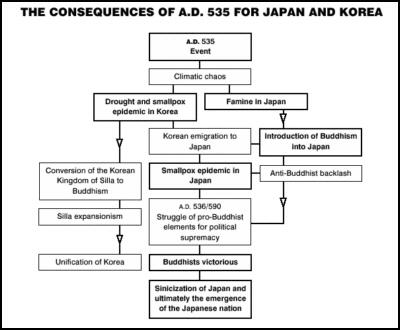

Typically, famines force their desperately hungry victims to move around, often traveling substantial distances, in search of food—and then to congregate at those few places where food or water is still available. The combination of population movement and temporary population concentration triggers epidemics. The increased mobility spreads disease much faster than normal, as do the higher population densities, achieved where starving people congregate. Thus, endemic disease quickly becomes epidemic disease.

Significantly, the Korean chronicle, the

Samguk sagi,

says that an epidemic did strike in exactly the right year—536. It is the only epidemic recorded by the

Samguk sagi

for the entire sixth century, so it must have been very serious indeed. Evidence from Japanese sources suggests that the disease was probably smallpox (or possibly measles, a malady capable of causing almost as many deaths as smallpox in nonimmune populations).

For centuries there had been intermittent waves of migration from Korea to Japan, and during the first four decades of the sixth century there was a steady flow of Korean immigrants—farmers, scribes, metalworkers, and others. The numbers involved were so substantial that they began to affect Japanese politics. One of Japan’s top aristocratic families, the Soga, aligned themselves with the foreigners and with foreign—that is, Buddhist and Chinese—culture in general.

The

Nihon shoki,

referring specifically to immigrants in an entry for the year 540, says they were gathered together to be counted and that there were 7,053 households. The counting operation—the first of its kind mentioned in the chronicle—suggests that the 530s had seen a particularly large flow of migrants to Japan, probably partially as a result of the famines and epidemics.

In Japan, the “yellow gold cannot cure hunger” edict, reported by the

Nihon shoki,

suggests that the king and his court were extremely concerned about the situation. That entry is quickly followed by one outlining how supplies of grain are to be transferred from various districts to other areas. Grain was to be dispatched, for instance, to one district where a granary was to be built, “thus making provision against extraordinary occasions and long preserving the lives of the people.”

The East Asian region seems to have continued to endure climatic problems and famine for several years. Mainland sources cite problems in China between 535 and 538 (see Chapter 19), and it is likely that Japan experienced similar problems.

Against the background of these problems (and perhaps specifically as a worthy and placatory religious act in troubled times), the king of southwest Korea (Paekche) decided in 538 to send a religious mission to the Japanese royal court. The mission presented the Japanese king, Senka, with a gold and copper image of the Buddha, several ritual Buddhist banners and umbrellas, and a number of sacred books. The head of the mission is said to have told the king that Buddhism “is, among all doctrines, the most excellent,” and that “every prayer is fulfilled and naught is wanting.”³

Paekche had been Buddhist for 150 years and is not known to have ever bothered to send a religious mission to the Japanese royal court before. And despite the fact that most of Korea and much of China had also been Buddhist or partially Buddhist for 150 and more than 350 years, respectively, Japan—even the continentally inclined aristocrats of the Soga family—had shown no interest in converting to Buddhism. But the situation in the 530s was unprecedented. The entire region was suffering from famine, and—as in Silla three years before—many must have felt that the strongest possible magic and/or the help of the strongest possible god was required to return nature to normalcy.

Yet there were others who were frightened that during a crisis it might be particularly unwise to offend the traditional native gods of Japan by worshiping a foreign deity. The ironworking, armor-making Mononobe aristocratic clan and the Nakatomi military aristocratic family warned the king of this in no uncertain terms, according to the

Nihon shoki

: “Those who have ruled [this kingdom] have always made it their care to worship in spring, summer, autumn and winter, the 180 gods of heaven and earth, and the gods of the land and of grain. If, just at this time, we were to worship in their stead foreign deities, it may be feared that we should incur the wrath of our national gods.”

The king therefore decided on a compromise. The leading enthusiast for adopting Buddhism, the head of the Soga clan, would be allowed to worship the foreign deity—as an experiment.

The Soga clan leader, Oho-omi, “knelt down and received [the statue of Buddha] with joy,” says the

Nihon shoki.

“He enthroned it in his house,” and then converted a second building into a temple. But then disaster struck. A catastrophic epidemic (probably smallpox) broke out in Japan. Vast numbers of people died. Because Japan had almost certainly not experienced smallpox for many generations, if at all, there was virtually no immunity.

“Pestilence was rife in the land, from which the people died prematurely. As time went on, it became worse and worse and there was no remedy,” notes the

Nihon shoki.

In those areas of Japan that were affected—certainly all those with relatively high population densities—it is likely that 60 percent of the population died. At first the disease would have produced flulike symptoms (fever, backache, headache), often followed by coughing and diarrhea. A rash—similar to that experienced in scarlet fever—would then have appeared. Victims would have felt as if they were on fire or constantly being scalded with boiling water. The

Ni

hon shoki

later describes sufferers as saying “our bodies are as if they were burned.” Then the nature of the rash would have changed. Starting densely on the head and progressing downward, but particularly dense also on the hands and feet, hundreds of sores (also referred to later in the

Nihon shoki

) would have began to appear on the victim’s skin. Each sore would have started as a small bump, metamorphosing into a clear blister and finally into a larger pustule.

Five percent of the sufferers would have died in the first few days from internal bleeding, while a further 5 percent would have perished as the sores took hold and their fever soared to 104 degrees Fahrenheit. The great majority of sufferers would probably have survived the smallpox virus but been killed by pneumonia (30 percent) and septicemia (also 30 percent) after the virus had stripped away the protective mucosal cells in the nose, throat, and eyes, thus allowing secondary bacterial infection.

In the devastated areas of Japan, nine out of every ten people probably contracted the virus, and only three out of those nine are likely to have survived it. In these circumstances it was therefore not surprising that the king’s decision to allow the Buddha to be worshiped was seen as the cause of the epidemic.

Opponents of Buddhism reasoned that the native gods of Japan were understandably angry. Those gods were the deities of what is today the Japanese Shinto religion. Known as the

kami,

they fell into five main categories: those that lived in trees, tall thin rocks, mountains, and other naturally occurring objects; those associated with particular crafts or skills; those that protected a specific family or wider community; those that were once living human beings, including some ancestors; and special elite deities such as the sun goddess and the two gods who were said to have created the islands of Japan.

The

kami

were regarded as having no shape of their own and had to be summoned by a shaman (priest) to enter an object whose form they could then adopt. It was generally believed that the spirits preferred long thin vessels to inhabit—magic wands, banners, long stones, trees, specially made dolls, and even living human beings. These humans—mediums—tended to be women and allowed their bodies and their voices to be literally taken over by the gods. The king himself may even have been seen as a rare male medium whose body was permanently “borrowed” by his divine ancestor, the sun goddess. Thus, the king was seen as a receptacle, a vehicle of the divine.

As the smallpox epidemic devastated Japan, the Mononobe and Nakatomi clan heads are said in the

Nihon shoki

to have implored their king to get rid of the Soga leader’s Buddha statue: “It was because thy servants’ advice on a former day was not accepted, that the people are dying thus of disease. If thou dost now retrace thy steps before matters have gone too far, joy will surely be the result! It will be well promptly to fling [the statue] away and diligently to seek happiness in the future.”

The king had little option but to agree. In a sense, the Buddha had indeed been responsible for the epidemic, for the disease had arrived from Korea as an unwelcome part of the package of “things foreign” that the Soga had been enthusing about.

“Let it be done as you advise,” the

Nihon shoki

says the king told his critics. “Accordingly,” the chronicle continues, “officials took the image of the Buddha and abandoned it to the current of the canal of Naniha. They also set fire to the [Soga leader’s Buddhist] temple, and burned it so that nothing was left.”

The row over Buddhism and the smallpox catastrophe must have opened up a vast political rift within the body politic of Japan, for in the midst of the epidemic and the religious recriminations (or immediately after them) the king was assassinated. It was the first known royal assassination in Japanese history. It is likely that the slaying of King Senka was carried out by the Soga clan, presumably angry at the way in which the monarch had capitulated to Mononobe and Nakatomi demands in the Buddhism row.

4

Certainly the next king, Kimmei, was backed by the Soga clan, and Soga notables became his key advisors, ministers, and affines. The Buddhism row and opposition to the Soga and their foreign friends and ideas forced the clan to push ruthlessly for a stronger monarchy over which they alone could have control. The rest of the aristocracy experienced a comparative decline in power.

The king was a vehicle through which the Soga, with their ideas of Chinese and Korean origin, reconditioned and transformed Japan. It was important, therefore, from their perspective to build up the status of the king vis-à-vis the rest of the non-Soga elite. When Kimmei died in 571, he (in contrast to everyone else) appears to have been buried in a huge moated tomb over a thousand feet long—the Mise Maru Yama, near the ancient city of Nara. In traditional Japanese elite style, it was built as a vast keyhole-shaped step pyramid, its sides bedecked with ritual vessels and parasols protected by life-size ceramic guardsmen, its summit topped by an elaborate replica palace. It was the last giant tomb of its type ever constructed.

The Soga appear to have soon tried once again to introduce Buddhism. In 584, apparently in an attempt to use Buddhist prayer to defeat another smallpox outbreak (of which there had been several since the disease’s initial incursion in the 530s), they set up a temple and had it consecrated by a Korean Buddhist priest. But the anti-Buddhist (and anti-Soga) political elements seized on the opportunity to revive the objections that had been raised four and a half decades earlier.

5

The new generation’s Mononobe and Nakatomi clan leaders are said in the

Nihon

shoki

to have chastised the new emperor, Bidatsu, for allowing the Soga to build a temple: “Why hast thou not consented to follow thy servant’s counsel? Is not the prevalence of disease from the reign of [the old king] down to thine, so that the nation is in danger of extinction, owing absolutely to the establishment of the exercise of the Buddhist religion by [the] Soga [leader].” The king replied: “Manifestly so: let Buddhism be discontinued.”

6

The Soga had misjudged the situation. Power was visibly slipping from their grasp as their archrivals, the Mononobe clan, demolished the temple and burned it together with the Soga’s cult statue of Lord Buddha. The

Nihon shoki

even describes how child Buddhist nuns of the Soga clan were imprisoned and flogged.

The very outbreak of smallpox that had encouraged the Soga to call for the Buddha’s help in 584 and which had rekindled the religious hostilities now spread to the royal palace, and the king himself died of it.

“The land was filled with those who were attacked with sores and died thereof. The persons thus afflicted said: ‘Our bodies are as if they were burned, as if they were beaten, as if they were broken.’ ” The words do accurately describe the experience of having smallpox, especially during the second week of the disease, but the phrases were also no doubt meant to reflect the notion of divine vengeance upon those who attacked Buddhism, its practitioners, and its houses of worship. After all, the

Nihon shoki

was written by the eventual victors in this long process—the Buddhists.

The Soga clan soon saw the need for ruthless action to regain political control after this debacle. So when the next emperor, Yomei, contracted smallpox in 587, and when his wish to seek Buddha’s help in saving him from death was thwarted by the opposition, a pro-Soga royal prince murdered a key member of the opposition, the Nakatomi clan leader.

7

The murder may have helped bring life to Japanese Buddhism, but it certainly did not save the king, whose “sores became worse and worse” before he finally expired.