Cat and Mouse

Authors: Tim Vicary

Cat and Mouse

Tim Vicary

First published as an ebook by White Owl Publications Ltd 2012

Copyright Tim Vicary 2012

ISBN 978-0-9571698-6-9

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention

No reproduction without permission

All rights reserved.

First published in Great Britain by Simon & Shuster Ltd in 1993

Copyright Tim Vicary 1993

First Published in Great Britain by Pocket Books, an imprint of Simon & Shuster 1993

The right of Tim Vicary to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988

Other e-books by Tim Vicary

Historical

The Blood Upon the Rose

(Love and terror in Ireland, 1920)

The Monmouth Summer

(Love and rebellion in 1685)

Crime and Legal Thrillers

A Game of Proof

(The Trials of Sarah Newby, book 1)

A Fatal Verdict

(The Trials of Sarah Newby, book 2)

Bold Counsel

(The Trials of Sarah Newby, book 3)

Website:

timvicary.com

Twitter:

@TimVicary

Table of Contents

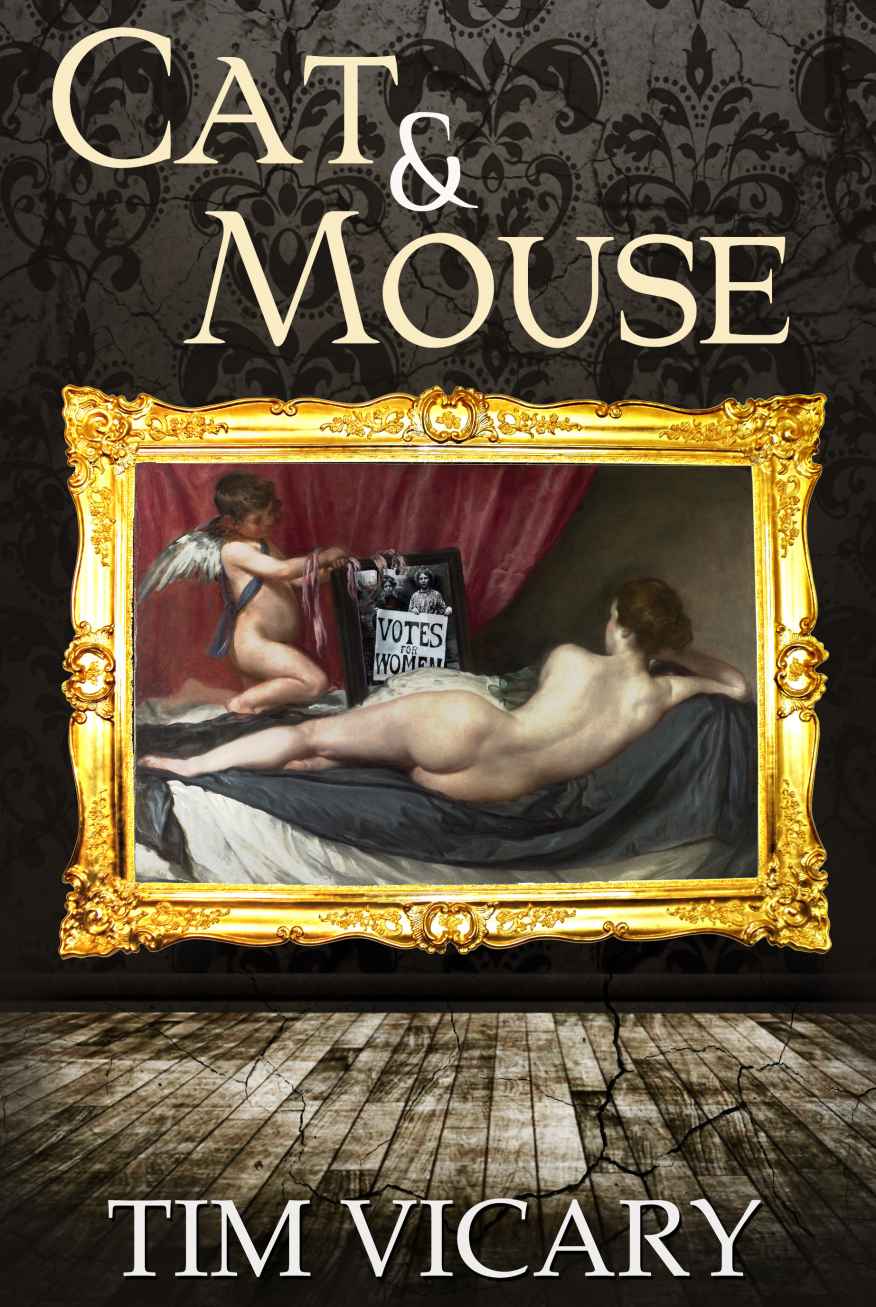

Anyone well acquainted with the history of the suffragette movement will know that the action described in the first chapter of this novel was in reality performed by the suffragette Mary Richardson on 10 March 1914. It seemed to me such an unusually striking and symbolic act that I have taken the liberty of borrowing it, and slightly changing the date, for the purpose of my story. My character Sarah Becket, however, is entirely fictional and intended to bear no other resemblance whatsoever to the real historical character Mary Richardson.

At exactly the same time as women were being imprisoned for demanding the vote, many influential men were strongly opposed to the government's policy of giving Ireland Home Rule. They felt that a Home Rule Parliament in Dublin, with a Catholic majority, would be a dagger blow to the heart of the British Empire. The Ulster Unionists regarded themselves as staunchly loyal to the King and Empire. They formed an army — the Ulster Volunteer Force — which threatened the United Kingdom with civil war unless Ulster, the north-eastern province of Ireland, was excluded from the Home Rule bill.

Unlike the suffragettes, none of these men was ever arrested for this open defiance of Parliament, and their protest was largely successful.

Like the eternal war between women and men, the results of that protest remain with us today.

‘The real cure of the great plague is a two-fold one – Votes for Women … and chastity for men.’

Christabel Pankhurst

The Great Scourge and How to End It, 1913.

‘It is reasonable to assume that Germany had secret agents in Ulster in 1914.’

ATQ Stewart

The Ulster Crisis, 1967.

Sarah

‘L

OOK OUT! Oh, sorry, ma'am, never saw yer.’

‘What? Who are you — oh, I see. It doesn't matter.’

‘Beg pardon, ma'am. I'm sure.’ The two coster boys, grubby and boisterous in their flat caps and ragged, oversize jackets, scurried away across the square. As they went they winked and grinned at each other, knowing they had made a discovery. They were connoisseurs of street life and there was something about the woman that drew their attention. A few yards away they glanced back over their shoulders to make sure, and then, their suspicions confirmed, parked themselves calmly under one of the great lions of Trafalgar Square to watch. One of them shied a pebble at the pigeons as they waited.

There was nothing particularly strange about the appearance of the woman. She was fairly tall, about five foot eight perhaps, and quite slim. Between thirty and thirty-five years old. She wore a long grey ankle-length skirt belted at the waist, with a pleated jacket with puffed sleeves above, over a white blouse buttoned up to her chin. On her head was a hat with red and yellow feathers in it. Nothing unusual about that — they were the clothes of a respectable, well-dressed lady — perhaps even a rich one, for the fur of the muff she held in front of her to warm her hands in was expensive, thick and ostentatious. The muff was rather odd though, because it was a fresh, sunny day in April, and she had not chosen to wear a coat.

But it was the look on her face that had struck the boys. When they had bumped into her she had, at first, stared right through them, then started away as though they were trying to attack her. The woman's face was pale, white as a cloud, the eyes in it burning like coals. An attractive face perhaps, with smooth skin and soft curling brown hair, but that was not what interested the boys. It was the haunted look that riveted them, the idea that she might be a ghost, a woman who scarcely knew where she was.

‘What d'yer reckon?’ the elder boy asked, taking a bite from an apple which he had purloined from a grocery stall in Charing Cross. The odd behaviour of the woman was all part of the joy of observing the eccentricities of the rich. ‘Going to kill herself, maybe?’

He glanced hopefully at the motor omnibus which was trundling towards them at nearly ten miles an hour, a few feet from the pavement where the woman stood.

‘Dunno,’ his mate said, judiciously. ‘Be as good as that, anyhow. You wait and see.’

The other curious thing about the woman was that she stood absolutely still. All about her was movement. Nannies stood by their perambulators talking while their charges cooed at the sky or toddled across Trafalgar Square in pursuit of the pigeons. Amongst them passed office boys, servant girls, city gents in top hats and striped trousers hurrying to get somewhere. The street in front of her was thronged with motor omnibuses, hansom cabs, horsedrawn delivery wagons, and messenger boys on bicycles. All of them hooted, shouted, and jangled past each other. The woman seemed to stare right through them, intent on some vision only apparent to herself. In the whole square, she and the boys were the only living creatures that did not move.

As the seconds lengthened into minutes, the boys' attention deepened, hunters sure of their quarry. Once or twice she swayed, as though almost too weak to stand, then checked and held herself rigidly upright. But still she did not move.

When nearly three minutes had passed, the elder boy turned to his mate, a broad grin on his face.

‘You wait, Jem,’ he said. ‘This one’s going to be good.’

Sarah Becket did not know she was standing still. Her mind was too busy. It was focussed on one ridiculous, irrelevant thought that got in the way of everything she had planned.

She thought: the Gallery is too big.

She had seen the National Gallery many times before but never really looked at it. It was a place she had visited as a child in school parties to learn about art, and later, with Jonathan when they were courting, because it was a convenient, respectable place to meet unchaperoned.

She had never looked at the building itself before.

But today, with the meat knife scratching her wrist inside her muff, she saw it for the first time.

It had been built while Queen Victoria was still a child, three-quarters of a century ago — a huge, confident, proud building. There were two sets of stone steps leading up to the portico and the main entrance. The pillars supporting the entrance were as tall as forest trees. They were linked by a long balustrade to similar rows of columns away to the right and left. In the middle of the roof was a beautiful glass cupola. Everything about the building proclaimed the glory of culture and education. It looked as solid and immovable as the Establishment of the British Empire itself.

And she, Sarah Becket, a woman who had learnt all her life to obey and reverence everything this building stood for, was about to attack it.

I could always go home, she thought. No one need ever know, this is not planned or sanctioned by the movement as the other things were. I don't have to do this. I could go to meetings and large demonstrations where I would have the support of other women around me. That would be easier. I could do that as I have done before. Or I could just turn round now and go back to Jonathan and smile and keep my promise to stay out of prison and try to be a good wife and pretend I know nothing at all about where he goes when . . .

That’s not the real reason. It's because I can't just do nothing, and leave Mrs Pankhurst to die.

She broke out of her trance and stepped off the pavement into the road. A bicycle bell rang furiously in her ear and a baker's delivery boy swerved round her, cursing and clutching at the loaves in the basket over his front wheel. Sarah stepped back, took a deep breath, and looked around her.

If I cannot even cross the road I will never manage it.

She waited for a gap in the traffic, walked across, went up the left-hand set of stone steps to the main entrance. It was like walking through water . . . At each step the air resisted her, her muscles weakened, she wanted to turn and run or just fall down and weep.

Mrs Pankhurst was arrested again yesterday, she thought — the seventh time for the same offence. She could hardly stand last time I saw her. In prison she doesn't eat and walks up and down her cell for hours every night. She will be dead soon — she is giving her life for feeble creatures like me. I know what it's like in prison, I've been there. I must force them to let her out. I'm doing this for Mrs Pankhurst.

Not Jonathan. Forget

him.

She walked through the great oaken doors. A uniformed commissionaire bowed stiffly to her. She found herself looking at his arms and face, thinking, he doesn't look an unusually strong man, or cruel. Will he hurt me very much, when I have done it?

Something not quite so polite, a little suspicious, came into the man's eyes. Women were suspected everywhere these days and Sarah realised she had stared at him a moment too long.

The shock gave her courage, made her begin to think clearly at last. It would be too, too stupid to come this far and fail, just because I acted feebly and looked like an idiot. After all, this man is just a servant, for heaven's sake.

She turned back and spoke to him. Her voice came out cool, distant, quite normal. A well-bred lady used to the deference of menials.

‘Good morning. I’ve come to see the Spanish exhibition. It is here, isn't it?’

‘That’s right, ma’am. Upstairs, in room 17. Would you like a catalogue?’

‘I would, thank you.’ Then, as he turned to reach for one on the desk behind him, she realised the difficulty. How could she pay for and accept the catalogue while she was carrying the muff with the knife inside it? She had a small purse in there too, in a pocket in the lining, but the knife was two inches wide and over a foot long — far too big and heavy to fit into her purse. And if he saw it!

It was too late to back out now. Carefully, trying not to look as though she was fumbling, she withdrew the purse from the pocket inside the muff and held purse, muff and knife all in the left hand together, while she fished the money out with her right.

‘Thank you,’ she said. Even to herself her voice sounded small, nervous, flustered.

The commissionaire took her money and held out the catalogue.

It was a big catalogue, with expensive reproductions of the paintings. Oh God, she thought. I don't need this at all. But to go in without one would look abnormal, surely? And people everywhere are on the lookout for suffragettes. This is much harder than throwing stones or marching in a demonstration.