Casket of Souls (3 page)

S

EREGIL

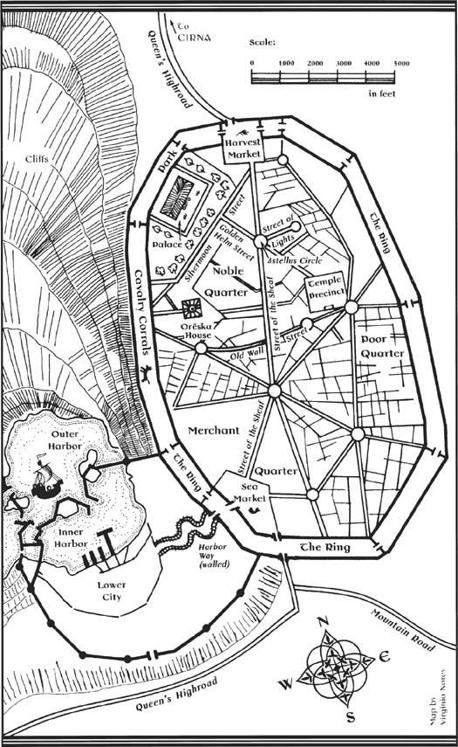

hadn’t been sure what to expect—or rather, he hadn’t expected much. This sweltering, run-down little theater in Basket Street used to cater to merchants of middling means with aspirations to culture, but who had neither the purse nor polish for the likes of the Tirari in the Street of Lights across the city. This place had been shuttered last he knew. The proscenium’s faded paint was peeling, its gilt dull, and the footlights flickered in the draft. Only the scrim behind the stage was new, expertly painted to suggest a dark, forbidding forest.

The theater was barely large enough for a hundred people, most of them groundlings in front of the raised stage. It was nearly full, and the smell of overheated bodies was already oppressive. It was unusual for it to be this hot so early in the summer.

“Are you certain this is the right theater?” asked Duke Malthus as he handed his wife Ania, Lady Kylith, and her niece Ysmay into their chairs.

“I was just wondering the same thing myself,” Seregil remarked, settling cautiously into a rickety chair between Alec and Kylith.

“Of course it is!” Kylith chuckled, tapping them both playfully with her fan.

Malthus and Kylith were considerably older than Seregil appeared, but he’d known them both in their youth. Malthus had risen to become one of the queen’s senior exchequers. He had a short cropped beard but wore his grey hair to his

collar—rather daring for a man in his position. Kylith, a former lover, was one of Seregil’s closest friends, and an unimpeachable source of society gossip.

Seregil dabbed the sweat delicately from his upper lip with a lace-trimmed handkerchief and scanned the crowd, acknowledging those he knew—merchants and sea captains mostly—who puffed up among their friends at his notice. Even at this level of society, whom you knew, and whom you were known to know, meant a great deal. Seregil, the infamous Aurënfaie exile, had made his living playing that game in Rhíminee for a good many years now.

He and his party were certainly attracting looks and whispers. Lady Kylith’s elaborately coiffed hair sparkled with jeweled pins as she murmured something to Duke Malthus. As always, she, Ania, and Ysmay were dressed in the height of summer fashion in light silks and jewels; here they looked like swans among ducks. Seregil supposed they all must. No doubt there were a few cutpurses in the audience below, sizing them up for later.

Seregil and Alec cut quite a figure themselves, two handsome, lanky young men—one dark-haired, one fair—dressed in long linen summer coats stitched in gold, fawn breeches, and well-polished boots. Seregil’s long, dark brown hair was caught back with a thin red silk ribbon that matched his coat. Alec’s thick blond braid hung down the back of a coat the same dark blue as his eyes.

Half-blood

ya’shels

like Alec aged a bit more quickly at first, but he still looked younger than his soon-to-be twenty-one. He had something of the fine ’faie features of his mother’s people, and was likewise beardless, but had his human father’s coloring.

Seregil played the role of a dissolute young exile that was only half true; he wasn’t particularly dissolute, though he played the part well. He and Alec were well known for carousing with the young blades of the nobility and a good many not-so-young, like Kylith and Malthus. But they managed to stay just on the boundary of respectability, and when they happened to stray outside it, Seregil’s distant relation to the royal family made up the difference. Handsome, foppish,

and exotic, the grey-eyed ’faie was known to be somewhat well connected but of little importance.

Their true vocation would have raised more eyebrows than their dissolute ways, if it ever came to light.

“I don’t suppose you’ve heard the latest news from the front?” asked Malthus.

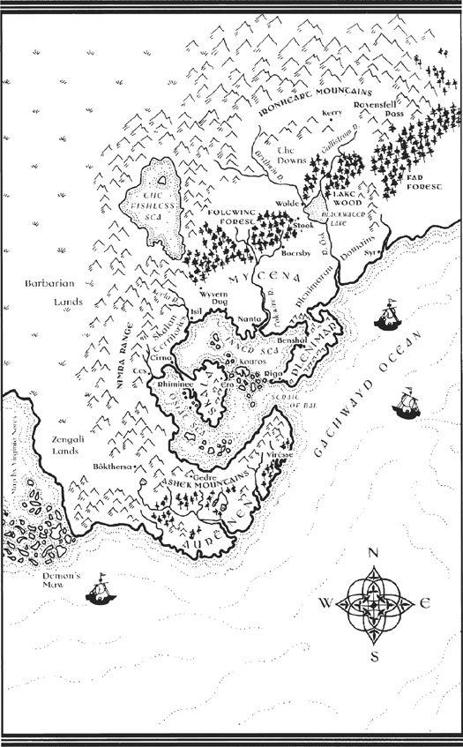

Queen Phoria was still at war with the Plenimarans; the army had left winter quarters two months ago and marched north again to the battlefields of Mycena.

Malthus leaned closer to Seregil and lowered his voice. “The heralds will be announcing it tomorrow, so I suppose there’s no harm in my telling you. The Overlord sued for a parlay. Phoria refused. She’s sworn to drive the enemy all the way back to Benshâl and crush them on their own ground.”

Seregil shook his head. “She means to end the endless conflict. Do you think she can do what her mother couldn’t?”

“Prince Korathan seems cautiously optimistic.”

The door opened again, and Lord Nyanis and his much rowdier party spilled in and noisily ascended to the far box. He and his companions had brought several pretty courtesans from the Street of Lights as their companions, and it was evident they’d all had a lot of wine. Among them was brown-haired Myrhichia from Eirual’s brothel, with whom Alec had once spent a night. Seregil was not the jealous type, particularly since he’d taken Alec there for that very purpose. She waved to them when her partner for the evening wasn’t looking, and Seregil blew her a kiss. Alec shyly waved back.

Nyanis spotted them and shouted over, “We’re going gambling after this. You must come with us!”

Seregil gave him a noncommittal wave.

“I haven’t been to the theater in weeks. I hope these players are all you claim, my lady,” Alec was saying to Kylith.

“And that we don’t go home with fleas,” Seregil muttered, scratching at a persistent itch in the crook of his left arm.

“Count yourselves lucky to be under a roof, my dears,” Kylith replied. “Until recently, this company was performing in the streets of the Lower City. They’re refugees from Mycena. They barely escaped with their lives when the Plenimaran army overran Nanta this spring.”

Mycena had always been the battleground when Plenimar and Skala went to war. Those who could fled north up the Folcwine, or south to Skala. There were Mycenian enclaves up and down the northeastern shore, and quite an alarming number had found their way to Rhíminee, thinking to make their fortune here. Most were quickly disillusioned. The tenements around the Sea Market and Temple Square were crowded with families eking out a living any way they could, with the unluckiest driven into the abject poverty and degradation of the south Ring—that no-man’s-land between the inner and outer city walls.

This troupe of players seemed to be among the lucky few to advance their fortunes, having attracted the attention of people like Kylith, who’d heard of them from her seamstress. Like Seregil, she never allowed rank to get in the way of anything that might prove amusing.

“What’s the play called?” asked Malthus.

“The Bear King,”

Kylith told him. “Have you heard of it, Seregil? I never have.”

“No, but I’m no expert on Mycenian theater. I have heard it can be a bit dull.”

“Not this play, apparently.”

Just then the sound of a drum began backstage, slow and deep as a heartbeat. An imposing, red-haired man with a long, solemn face stepped onto the stage, dressed in what appeared to be a poor approximation of ancient noble garb cobbled together from some ragman’s cart. His eyes, outlined in black, seemed to look to some far-off vista as he raised a hand for silence.

“Long ago, in the time of the black ships, a caul-shrouded babe was born deep in the wilderness of the eastern mountains,” he intoned, his voice deep and resonant. On the stage behind him, a girl in a tattered gown and veil writhed and cried out on the boards, then pulled a painted doll from beneath her skirts, its face covered with a veil.

“There aren’t any eastern mountains in Mycena,” Alec whispered.

“Dramatic license,” Seregil murmured back with a smile.

The narrator continued. “And when the caul was lifted,

eyes like gems of ice did steal the very breath from his mother’s lips before she could give suck.”

The girl expired with a groan. Someone offstage did a credible job mimicking a baby’s crying. Then an older actress draped in a fusty bearskin shuffled out and gathered up the doll, rocking it in her arms.

“A she-bear found the babe and suckled it as her own until a huntsman struck her down.”

An older man with grizzled grey curls leapt onstage with a crude lance and mimed running the bear through. When she expired, the man peeled the skin off her and wrapped the doll in the edge of it.

“The huntsman wrapped the child in the pelt of the she-bear that had nursed him and took him back to his wife,” the narrator went on. There was no chorus, but he already had the crowd spellbound.

Despite the raggedness of his costume, the tall narrator commanded the stage as well as any player Seregil had seen at the Tirari this season.

The hunter walked around the edge of the stage, while the woman who’d played the bear took her place on the far side in a different veil and held out her arms to the child. Together the couple walked offstage.