Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone (10 page)

Read Capone: The Life and World of Al Capone Online

Authors: John Kobler

In 1900 the nonpartisan Municipal Voters' League, an organization dedicated to the overthrow of predatory politicians, was seeking a nominee it could support for Second Ward alderman. One Republican citizens' group proposed Bill Thompson, a towering athlete with a snaggled front tooth who had brought glory to the Chicago Athletic Association in half a dozen different sports. By way of recommendation the chairman of the sponsoring group pointed out: "The worst you can say about Bill is that he's stupid."

Thompson, who was then thirty-five, harbored only the feeblest interest in government. He had agreed to run to win a $50 bet. Born in Boston and reared in Chicago, he came from a line of New Eng land military and naval officers. His father amassed a fortune as a Chicago real estate dealer. He wanted the same kind of gentleman's education for his son that he himself had received back East, but mental effort pained Billy. The only reading he enjoyed were dime thrillers about the Wild West, and they filled him with longing for the life of a cowboy. He struck a bargain with his father: He would spend part of every winter at school in Chicago and the rest of the year on the Western range. He quickly adopted the idiom, manners and drinking habits of a frontiersman, and he never entirely discarded them. Between trips to Utah, Wyoming and Nebraska he attended a Chicago preparatory school, then a business college. His father's death in 1891 ended the Wanderjahre. He stayed home to keep an eye on the family real estate business. It was during his leisure hours-actually, most of the day-that he distinguished himself as an all-star athlete, the idol of Chicago youth.

As the Republicans' victorious "reform" alderman, Thompson was conspicuous by his absence. He had added sailing to his sporting skills, and he preferred racing a yacht on Lake Michigan to the tedium of aldermanic responsibilities. At what point political ambition seized him is not clear, but in 1902 he appeared on the Republican slate as a candidate for Cook County commissioner. He developed a natural gift for campaign tent oratory. He knew instinctively how to tickle the prejudices of ethnic and national groups. Though his bullroaring platform speeches ranged in content from the banal to the inane, Chicago's Irish and Italian voters responded enthusiastically when he vilified the British, calling them "seedy and untrustworthy." He won the election.

His rise in the Republican ranks was slow but steady, with an occasional minor setback caused by the exposure of some peccadillo, as when the Amateur Athletic Union suspended him and other CAA football players for professionalism or when, testifying in a separation suit brought by a woman against a friend of his, he had to confess that he used to frequent the Levee dives. He was forty-eight, running to paunch and jowl, his voice whiskey-hoarse, when the party elders began to see mayoral timber in him. "He may not be too much on brains," said Congressman Fred Lundin, their shrewdest strategist, "but he gets through to people." Lundin had once roamed the city as a medicine man, peddling nostrums of his own brew. He sold Thompson to the voters and taught Thompson how to sell himself. The Democratic opponent was a Catholic of German extraction, Robert M. Sweitzer.

Practically every plank in Big Bill's platform invalidated some other plank. It depended where he was campaigning. The war overseas had broken out four month before, and in German neighborhoods, the Chicago American reported, he sounded like "Kaiser Bill." In the German-hating Polish districts, meanwhile, his campaign workers were circulating handbills deriding "Sweitzer, the German candidate," and in the Protestant wards they warned that a vote for Sweitzer was a vote for the Pope. In the Irish wards Thompson lashed out at the English. Addressing native American audiences, he would wrap himself in the Stars and Stripes and invoke the spirit of George Washington.

He promised the reform groups strict enforcement of the antigambling laws, and he promised the gamblers a wide-open town. Speaking to the Negroes of the Second Ward: "If you want to shoot craps, go ahead and do it. When I'm mayor, the police will have something better to do than break up a friendly little crap game."

He further promised the Negroes: "I'll give you people jobs. . . . Only a good cowboy like Jess Willard [who had just defeated the Negro heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson, in Havana] could beat a good man like Johnson. Tomorrow the cowboy will be on your side."

To the wives and mothers of the silk-stocking wards: "I'll clean up this city and drive out the crooks! I'll make Chicago the cleanest city in the world! . . . I'll appoint a mother to the Board of Education! Who knows better than a mother what is good for children?"

He promised the drys he would uphold the state's blue law prohibiting the sale of liquor on Sunday. He promised the wets he would oppose all Sunday blue laws, and he wooed the saloon owners by signing a pledge to that effect. "I see no harm in a friendly little drink in a friendly little saloon," he said.

Big Bill Thompson won the 1915 mayoralty by the biggest plurality ever registered for a Republican in Chicago.

Within six months he had violated every campaign promise but one. He did keep Chicago wide open. After a flurry of token arrests in the Levee and elsewhere, a live-and-let-live policy prevailed anew. Slot machines manufactured by Chicago's Mills Novelty Company clicked and clattered away all over the city, with the bigwigs of City Hall getting a cut of the profits. The Sportsmen's Club, a Republican organization, was used as a collection agency for the graft. Not only gamblers, but saloon- and brothelkeepers received solicitations for $100 "life memberships" on club letterheads bearing the mayor's name. The members included Thompson's chief of police, Charles C. Healey; Herbert S. Mills, president of the slot machine company; Mont Tennes, the gambling magnate; Jim Colosimo, whose liquor license the mayor restored.

In preference to the big, easily raided whorehouses the principal vice mongers now maintained numerous discreet "call flats." The whores would seek their customers in dance halls, also owned by the panders, and take them to the flats. In an expose of the system Major Funkhouser put the total number of flats at 30,000. Thompson stripped him and his Morals Squad of all authority.

The first eight months of the Thompson regime produced twice as many criminal complaints as the entire preceding year. "The police department is just a big sewing circle," said Alderman Charles E. Merriam, a political science professor at the University of Chicago and the leader of a reform faction. Chief Healey, who had begun his tenure with a declaration of war against the underworld, ended it exposed as the boss of the city's biggest graft ring, an associatee of malefactors like Mike de Pike Heisler. In January, 1917, he was indicted for graft *and bribery along with three other members of the department, four underworld magnates and an alderman. As its main exhibit at the trial, the prosecution introduced a notebook which had been found in the possession of a North Side police lieutenant. The first pages listed shady hotels and their weekly tributes of $40 to $150. Next came brothels, houses of assignation and gambling dives, some marked "the chief's places," indicating that all the payoff money went directly to Healey, others marked "three ways," which meant that Healey shared the loot with Police Captain Tom Costello, Heisler and one Billy Skidmore, a bondsman, gambler and saloonkeeper. A fourth list named the saloons the police allowed to operate illegally after I A.M. and on Sunday. A fifth list of gambling houses and disorderly hotels was headed "Can't be raided" and a sixth, "Can be raided."

Healey retained two of Chicago's most successful criminal lawyers, Clarence Darrow and Charles Erbstein, and they won an acquittal. The jury, in fact, acquitted all nine defendants.

"Chicago is unique," said Professor Merriam. "It is the only completely corrupt city in America."

The contrast between Torrio's professional and private life amazed the few associates familiar with both. Catering to the vices of others, he himself had none. By temperament ascetic, he never smoked, drank or gambled. He ate sparingly. He eschewed profane and obscene language and disliked hearing it. He took no interest in any woman but his wife, Ann. With his small, dark, watchful eyes and thin, compressed lips, he seemed perpetually to be deploring the sinful ways of man.

In his daily routine he observed a clocklike regularity. Early every morning, attired in a suit of sober hue and cut, wearing no jewelry save his wedding ring, he would tenderly embrace his wife and either walk the three blocks from their flat on Nineteenth Street and Archer Avenue to his office on South Wabash or drive to Burnham. Then, for the next nine or ten hours he would attend to the minutiae of the brothel business, routing the whores from house to house in order to ensure the regular customers a continual change of faces, cutting corners on the whorehouse food, drink and linens, calculating the previous night's profits. He ascribed no humanity to the girls he handled. He regarded them simply as commodities, to be bought, sold and replaced when worn out.

Barring some crisis, Torrio would return home at six and, except for an occasional play or concert, not leave it again until morning. His wife would bring him slippers and smoking jacket. After supper they would play pinochle or listen to the phonograph. Torrio loved music and knew a good deal about it. He could follow a score and hold his own in a discussion with professional musicians. "He is the best and dearest of husbands," said his wife. "My married life has been like one long, unclouded honeymoon. He has done everything to make me happy. He has given me his wholehearted devotion. I have had love, home and contentment."

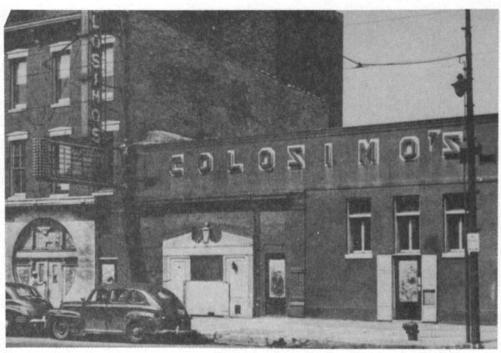

Colosimo found Torrio exemplary as a business manager. Between his nephew's efficiency and the lenience of Mayor Thompson he had become top dog among Chicago vice kings. His political value extended far beyond the Levee. With his City Hall connections, he no longer depended on Aldermen Coughlin and Kenna for protection. The roles were reversed. They went to him.

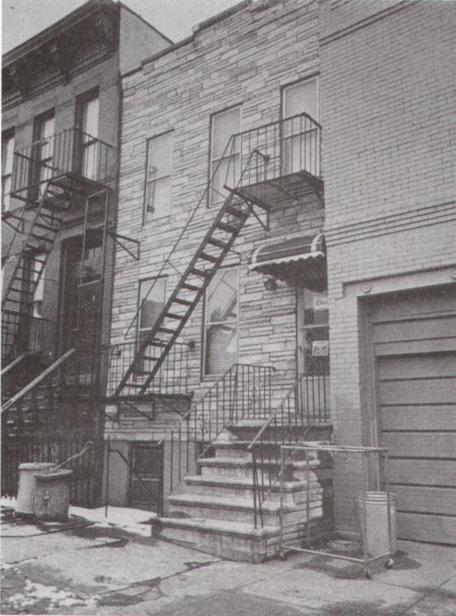

Garfield Place, Brooklyn, where the Capone children grew up.

Johnny Torrio (right), at the age of twenty-nine, shortly after his Uncle Jim Colosimo brought him to Chicago. Big Jim's father sits between them.

In its heyday, Chicago s plushiest pleasure palace. The second story was given over to gambling.

Chicago Historical Society.