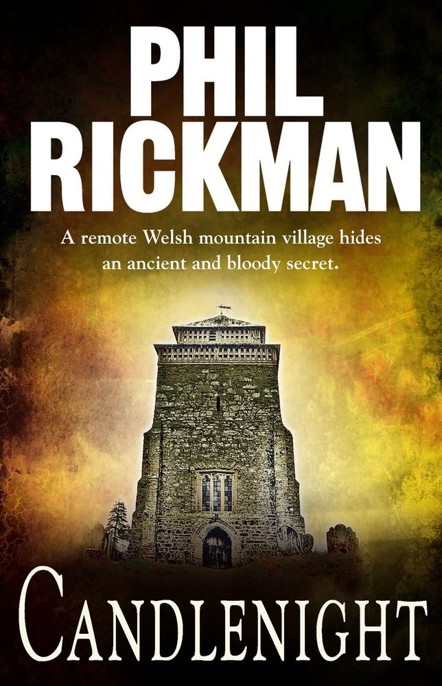

Candlenight

Part One

PORTENTS

Chapter I

Laughter trickled after him out of the inn.

Ingley's mouth tightened and he would

have turned back, but this was no time to lose his temper. In a hurry now. Knew

what it was he was looking for. Could almost hear it summoning him, as if the

bells were clanging in the tower.

Besides, he doubted the laughter was

intended to be offensive. They were not hostile in the village—yes, all right,

they insisted on speaking Welsh in public all the time, as if none of them

understood anything else. But he could handle that. As long as they didn't get

in his way.

"Torch," he'd demanded.

"Flashlight. Do you have one I could borrow?"

"Well . . ." Aled

Gruffydd, the landlord, had pondered the question as he pulled a pint of beer,

slow and precise as doctor drawing a blood sample.

The big man, Morgan somebody,

or somebody Morgan, had said, very deadpan, "No flashlights here.

Professor. Blindfold we could find our way around this place."

". . . and pissed," a man

called out by the dartboard. Blindfold and pissed."

Aled Gruffydd laid the pint

reverently on a slop-mat and then produced from behind the bar a big black

flashlight, "But we keep this," he said, "for the tourists.

Rubber, Bounces, see."

Morgan laughed into his beer, a

hollow sound.

"Thanks," Ingley said,

ignoring him. "I . . . my notes, And a couple of books. Left them in the

church. Probably there in the morning, but I need to know." He smiled

faintly. "If they aren't, I'm in trouble."

The landlord passed the rubber

torch across the bar to him. "One thing. Doctor Ingley. Batteries might be

running down a bit, so don't go using it until you need to. There's a good bit

of moon for you, see."

"Quite. You'll have it

back. Half an hour or so, yes?"

"Mind the steps now,"

Gruffydd said.

There was a short alleyway formed by the side of the inn where he'd

taken a room and the ivy-covered concrete wall of an electricity sub-station.

From where it ended at some stone steps Thomas Ingley could hear the river

hissing gently, could smell a heady blend of beer and honeysuckle.

This pathway had not been built

with Ingley in mind. The alley had been almost too narrow for his portly body,

now the steps seemed too steep for his short legs. On all his previous visits

to the church he'd gone by car to the main entrance. Hadn't known about the

steps until somebody had pointed them out to him that morning. The steps

clambered crookedly from the village to the church on its hillock, an ancient

man-made mound rising suddenly behind the inn.

As the landlord had said, there

was a moon—three parts full, but it was trapped behind the rearing church tower

(medieval perpendicular, twice repaired in the nineteenth century) and there

were no lights in the back of the inn to guide him up the steps. So he switched

on the torch and found the beam quite steady.

Ingley had lied about leaving

notes in the church. Kept everything—-because you couldn't trust anybody these

days—under the loose floorboard beneath his bed. He wondered what the hell he

would have done if one of the regulars had offered to help him. Can't go up

there on your own in the dark, Professor—break your neck, isn't it? He'd have

been forced to stroll around the place, pretending to search for his documents,

the tomb tantalisingly visible all the while, then have to wait for the morning

to examine it. Too long to wait.

He never put anything off any

more. If one had a line to pursue, strand to unravel, one should go on

regardless of ritual mealtimes, social restraints, the clock by which man artificially

regulated—and therefore reduced—his life.

And depressingly, with Ingley's

condition, one never knew quite how much time one had left anyway.

He set off up the jagged steps.

A bat flittered across the

torchbeam

like an insect. Bats, like

rats, were always so much smaller than one imagined.

Ingley paused halfway up the

steps. Had to get his breath. Ought to rest periodically—doctor's warning. He

scowled. Stood a moment in the scented silence. Did the sense of smell

compensate for restricted vision in the dark? Or were the perfumes themselves

simply more potent after sunset?

A sudden burst of clinking and

distant clatter, then a strong voice in the night. A voice nurtured, no doubt,

by the male choir and the directing of sheepdogs on windy hills.

"Professor! Dr. Ingley!

Where are you. man?"

Morgan.

Dammit

. Dammit. Dammit. Snapping

off the torch, he held himself very still on the steps. Or as still as one

could manage when one was underexercised. overweight and panting.

"Prof, are you all right?"

Of course I am. Go away. Go

away. Go away. Thomas Ingley stayed silent and clenched his little teeth.

Another voice, speaking rapidly

in Welsh, and then

Morgan said "

O'r gorau

" OK,

then—must mean that, surely. And the heavy front door of the inn closed with a

thunk that sounded final.

Ingley waited a while, just to

be sure, and then made his way slowly to the top of the steps. Emerging onto

the plateau of the churchyard, he stopped to steady his breathing. The sky was

a curious moonwashed indigo behind the rearing black tower and the squat

pyramid of its spire. A dramatic and unusual site in this part of Wales, where

most people worshipped in plain, stark, Victorian chapels—rigid monuments to

nineteenth century Puritanism. Even the atmosphere here was of an older, less

forbidding Wales. All around him was warmth and softness and musty fragrance; wild

flowers grew in profusion among the graves, stones leaning this way and that,

centuries deep.

Not afraid of graves. Graves he

liked.

"

Dyma fedd Ebenezer Watkins,

" the torch lit up, letters etched

into eternity. "1858-1909."

Fairly recent interee. Ingley

put out the light again, saving it for someone laid to rest here well over four

centuries before Ebenezer Watkins. Excited by the thought, he made straight for

the door at the base of the tower, straying from the narrow path by mistake and

stumbling over a crooked, sunken headstone on the edge of the grass. Could fall

here, smash one's skull on the edge of some outlying grave and all for nothing,

all one's research. "Don't be stupid," he said aloud, but quietly. He

often gave himself instructions. "Put the bloody light back on."

Followed the torchbeam to the

door, which he knew would be unlocked. "A hospice, sanctuary I suppose you

would say, in medieval times," Elias ap Siencyn had told him. "And

today, is there not an even greater need for sanctuary?" Impressive man,

ap Siencyn, strong character and strong face, contoured like the bark of an old

tree. Too often these days one went to consult a minister about the history of

his church to be met by a person in a soft dog collar and jeans who knew

nothing of the place, claiming Today's Church was about people, not

architecture.

At the merest touch the ancient

door swung inwards (arched moulded doorway, eighteenth century) and the churchy

atmosphere came out to him in a great hollow yawn. He was at once in the nave,

eight or nine centuries or more enfolding him, cloak of ages, wonderful.

All the same, was it not taking

tradition too far to have no electricity in the church, no lights, no heating?

Inside, all he could see were

steep Gothic windows, translucent panes, no stained glass, only shades of mauve

stained by the night sky. He knew the way now and, putting out the torch, moved

briskly down the central aisle, footsteps on stone,

tock, tock, tock

.

Stopped at the altar as if about

to offer a prayer or to cross himself.

Hardly. Ingley didn't sneer

this time, but it was close.

Table laid for God. A millennium or

more of devotion, hopes and dreads heaped up here and left to go cold.

Confirmed atheist, Thomas Ingley. Found the altar just about the least

interesting part of the church.

He'd stopped because this was

where one turned sharply left, three paces, to get to the secret core of the

place, the heart of it all. Simply hadn't realised it until tonight. Been up

here five times over the weekend. Missing, each time, the obvious.

Decidedly cool in the church,

but Ingley was sweating in anticipation and the torch was sticky in his hand. A

weeping sound, a skittering far above him in the rafters: bats again. Then a

silence in which even the flashlight switch sounded like the breach of a rifle.

Clack!

And the beam was thrown full in

the face of the knight.

Like a gauntlet, Thomas Ingley thought, in challenge. Slap on one cheek,

slap on the other. This is it. Lain there for centuries and nobody's given a

sod who you were or what you were doing here. But you've slept long enough.

Taking you on now, sir, taking you on.

The stone eyelids of the knight

stayed shut. His petrified lips wore a furtive smile. His stone hands, three

knuckles badly chipped, were on his breast, together in prayer. The beam of

light tracked downwards, over the codpiece to the pointed feet.

"All right, friend,"

Thomas Ingley said, speaking aloud again, laying the torch on the effigy, taking

out a notebook, felt-tip pen, his reading glasses. Nuts and bolts time.

"Let's get on with it."

He made detailed notes, with

small drawings and diagrams, balancing the notebook on the edge of the tomb beneath

the light. He drew outlines of the patterns in the stone. He copied the

inscriptions in Latin and in Welsh, at least some of which he suspected had

been added later, maybe centuries after the installation of the tomb. Tomorrow,

perhaps, buy a camera with a flash, do the thing properly. Tonight, just had to

know.

Finally he took from his jacket

pocket a retractable metal rule and very carefully measured the tomb. It was

about two feet longer than the effigy. The inscription in stone identified its

occupant as Sir Robert Meredydd. An obscure figure. If indeed, thought Ingley,

he had ever existed.

The main inscription, he was

now convinced, had been done later, the slab cemented to the side of the tomb;

he could see an ancient crack where something had gone amiss, been repaired. He

put away rule, notebook, pen, spectacles. Picked up his torch from the knight's

armoured belly.

Got you now, friend. Yes.

For a moment, in the heat of

certainty, all his principles deserted him and he wanted to tear the tomb open,

take up a sledgehammer or something and smash his way in.

Involuntarily, he shouted out,

"Got you!" And now he really did slap the effigy, full in its smug,

smiling face.

A certain coldness spread up

his arm as the slap resounded from the rafters.

Ingley stepped back, panting,

shocked at himself. He felt silence swelling in the church.

The knight's cold face flickered. The

torch went out.

Batteries.

Couldn't say he hadn't been

warned. Too absorbed in his work to notice it growing dim. He shook the torch;

a mean amber glimmer, then it died.